Originally published on GoshenCommons.org November 25, 2013

(UPDATE: The March trilogy is complete! Here’s what Book Three looks like, and you can get all three in a boxed set.)

Most of the comics I’ve reviewed in this blog have been for entertainment, but the history of comics is also closely tied with education. Comics versions of literary classics and the Bible, for example, have been created for audiences disinclined to sit down and read a book.

This sometime association of comics with educational purpose is part of why the genre is often dismissed by artists and art critics who consider any predetermined goal or meaning a corruptive influence on art. As high Modernist poet Archibald MacLeish famously put it in “Ars Poetica,” “A poem should not mean / But be.” Art in its “pure” state is (supposedly) objective, devoid of any specific point or purpose beyond artistic “expression.”

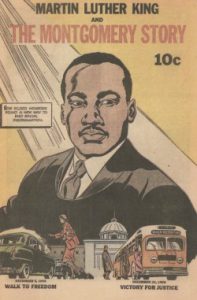

Plenty of comics—perhaps the majority—aim to tell good stories rather than communicate a particular purpose, but the history of comics with more specific political goals is just as rich and fascinating. One such artifact from the Civil Rights era is a comic produced in 1958 by the Fellowship of Reconciliation, or FOR.

“Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story” was designed to teach the fast-growing ranks of nonviolent protesters about the bus boycott in Montgomery, Ala., the site of Rosa Parks’s famous protest, and also to educate them in the most effective methods for continuing the practice in other locations.

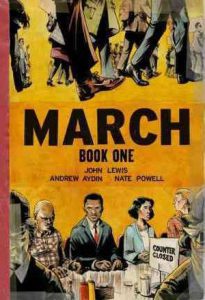

Congressman John Lewis, one of the most prominent surviving figures from the Civil Rights movement, was inspired by the 1958 comic book, and was convinced by his comics-nerd staffer, now co-writer, Andrew Aydin, to tell his own story in comic-book form. The result is “March: Book One,” the first of a projected trilogy.

Just released this past August to coincide with the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington, this first book details the early years of Lewis’ life, particularly his role in the successful lunch-counter sit-ins in Nashville. Illustrated by Nate Powell, this brilliant and gorgeous book manages to succeed in both the educational and artistic spheres.

For many of us, the phrase “Civil Rights Movement” has become oversimplified and monolithic, evoking statuesque images of Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, and a handful of other heroic figures, many of whose names only became well known once they had been murdered. This first section of John Lewis’s story, however, is about a very real person still at work in Congress, and still engaged in protest for social equality. (He just got arrested this past October for what he thinks was the 45th time—he ‘s lost count—at a Washington, D.C., immigration reform sit-in.) “March” illustrates how real people like Lewis, not just outsized legends, made the Civil Rights movement a success, and can continue to effect change in society.

The main storyline starts in the recent present, on the morning of President Obama’s first inauguration. Most of us can relate to Congressman Lewis in this opening scene: his groggy response to his alarm on that cold January morning is certainly one that most “real people” would understand.

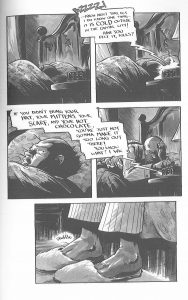

Lewis stops by his D.C. office on his way to the inauguration, and receives three surprise visitors, a mother and her two young sons. Readers learn Lewis’s backstory as he answers their questions about his life. It’s a bit of a clunky plot device, but the story that follows is so specific and well told that readers are unlikely to care how they got there. Lewis grew up on a farm in Pike Country, Ala., and when he decided as a child that he wanted to be a preacher, the family’s chickens served as his congregation:

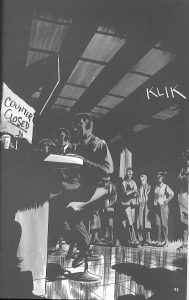

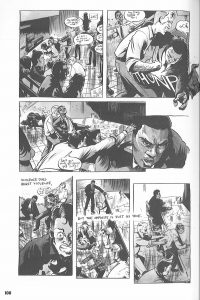

This image illustrates one of the most powerful tools of a black-and-white comics artist, the use of background contrast. Here are two different scenes of lunch-counter sit-ins from later in the book, and later in Lewis’s story:

Remember Scott McCloud’s discussion of the power of icons in “Understanding Comics,” which I referenced in my second post?

If we buy McCloud’s argument that iconic cartoon faces help readers project themselves into a story, then a comic book is the ideal medium to bring readers, especially young readers, into the story. Photographs and films have told this story, but their realistic representations tend to distance their viewers from the scene. Powell’s not-too-fuzzy but not-too-detailed faces help readers realize that they, too, could sit at those lunch counters if they were called to, if the need ever again arose.

The book closes with two calls, one from each of the main storylines. First, the phone on the left rings in Lewis’s Nashville dorm in 1960 with the news that the lawyer who defended the 82 protesters jailed after the sit-ins has been firebombed at his home. The incident pushes the mayor of Nashville to finally order the integration of the city’s lunch counters, yet the last few pages of the book make it clear that the battle is far from over. The final page returns to the recent present, with Lewis’s cell phone ringing in his office after he has left for the inauguration. We don’t yet know whom this call is from, or what it means that Lewis has left his phone behind and is unable to answer it, but we do know that we have two more installments to look forward to.

In my next post, I’ll review two books that represent history much further back and much further away. Gene Luen Yang, acclaimed author of, among many other works, the groundbreaking young-adult comic “American Born Chinese,” and co-author of Dark Horse Comics’ adaptation of the series “Avatar: The Last Airbender,” has just released a pair of linked books. “Boxers” and “Saints” tell the story of the Boxer Rebellion, each from a different perspective. I’ll review both books in two weeks, but if you can’t wait, you can find them at Better World Books in Goshen, Indiana, a much more pleasant place to get started on your holiday shopping than those big box stores.