Originally published on GoshenCommons.org September 2, 2013

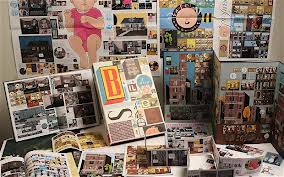

At the end of my last post about “image” in comics, I began discussing this week’s book for review—”Building Stories” by Chris Ware—which is really a box of 14 small books, pamphlets, magazines and even what looks like a game board. Here’s an image of the whole shebang from Britain’s newspaper “The Telegraph”:

I mentioned how reading this work is a visceral experience, much the way that rummaging through a box of papers and keepsakes in an attic can engage all five senses. Such physical reading experiences are increasingly rare in our new age of e-books, which might explain the mainstream success of “Building Stories”: it topped the bestseller lists from its fall release through Christmas 2012.

I mentioned how reading this work is a visceral experience, much the way that rummaging through a box of papers and keepsakes in an attic can engage all five senses. Such physical reading experiences are increasingly rare in our new age of e-books, which might explain the mainstream success of “Building Stories”: it topped the bestseller lists from its fall release through Christmas 2012.

The “book in a box” concept has been done before: perhaps the best known is B.S. Johnson’s 1969 novel “The Unfortunates,” and there have been multiple more recent contributions, such as the poet Ann Carson’s “Nox”—but none yet that I know of in graphic novel form. (Comments, please, if I’m wrong! And thanks to my colleague Ann Hostetler for showing me “Nox.”) Most of Johnson’s pamphlets were meant to be read in any order, but he did specify which should be read first and last, which provides focus and a framework for the story sandwiched in between.

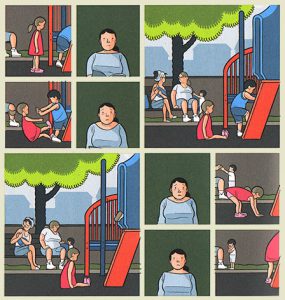

No such direction from Ware. Not only does he complicate the form and function of his work’s many pieces, but he also relinquishes control of the storyline entirely to the reader. Here are the basics: the main protagonist is an unnamed woman in Chicago who lost the lower part of one of her legs in an accident as a child. We see some flashbacks to her childhood, but we mostly follow her from her early 20’s as a graduate school art student into her middle age as a stay-at-home mom.

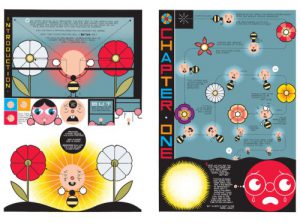

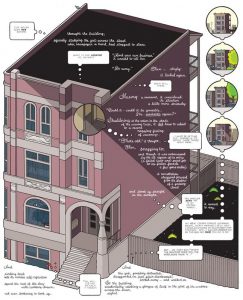

Other characters who briefly take on storytelling are an anxious and depressed bee named Branford and the Chicago apartment building that the woman lived in as an art student, on the top floor.

The building qualifies for the list of characters because it talks in the first person about its former and current inhabitants. Other characters from the apartment building, such as the bickering couple on the second floor and the aged landlady on the first floor, circle each other in minor but engaging storylines.

Most critics who have reviewed “Building Stories” so far find it A) groundbreaking, and worthy of recognition on the level of major literary masterpieces like David Foster Wallace’s “Infinite Jest” and Marcel Proust’s “Remembrance of Things Past.” They also find it B) depressing as all get-out. I wholeheartedly agree with A), and just as emphatically disagree with B). Yes, the main character is depressed, the rest of the people in her building are depressed, even the building itself and the insect life are depressed—but not depressing, I’d argue.

Image from The Comics Journal

Check out the above page, where the protagonist dreams that she finds a version of this very work on the shelves. Her daughter may dismiss the dream, but we realize that our depressed protagonist really has accomplished something significant: these six frames are the only ones in which she has gray hair, so we don’t know a lot about this stage in her life, but we do know that her daughter sees her as a success: “You’ve got your own business, Mom.” The protagonist may still feel guilty and embarrassed, but this revelation is a triumph. Even if you don’t happen to end your reading on this page, it gives the whole project purpose.

Clearly, A) and B) are more related than we might realize: the most “important” works are those with enough space for readers to fill in their own interpretations. To me, Ware’s point seems to be that although there might be a “proper order” in fiction, there isn’t in life, and there certainly isn’t a “proper order” in the way our memories flash and loop and pick moments in time as we’re rummaging through that box in the attic.

For my next post, I’ll get to that discussion I referenced last time: the way Ware contrasts straight-lined and geometric scenery with droopy, bulbous humans—and to pique your interest, check out the way these contrasts in Ware’s work echo and redefine the bubble-like landscapes of another iconic North American artist, Grant Wood. Here’s a link to a fabulous Grant Wood site created by Janet Haven of the University of Virginia American Studies Program: http://xroads.virginia.edu/~ma98/haven/wood/landscape.html

Thanks again to Better World Books, on Main Street in Goshen, where you can find “Building Stories” and many, many other fine comics.