Originally published on GoshenCommons.org September 30, 2013

Last post I finished my review of Chris Ware’s “Building Stories” by arguing its place in North American visual history. This week, something much lighter, but not to be underestimated: “Love in Yop City.”

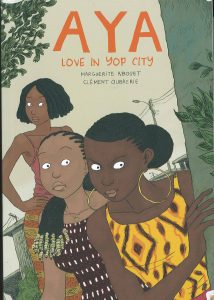

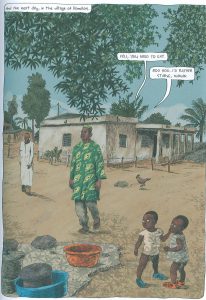

The story, by Marguerite Abouet, is the second in a series, and was just released in English translation by the Canadian publisher Drawn and Quarterly. Abouet, born in the Ivory Coast but raised in Paris, works with the French illustrator Clément Oubrerie. The series immerses its readers in the Ivory Coast of the 1970s—the country that Abouet knew before she moved to Paris at age 12.

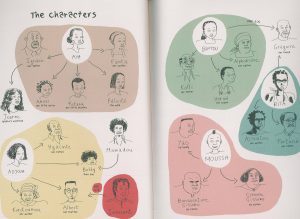

The key skill for reading “Building Stories” was the ability to slow down and notice small changes from frame to frame. With “Love in Yop City,” the challenge is to keep up with Abouet’s 10 main storylines; fortunately, she provides a visual cast of characters at the start of the book to help the reader navigate.

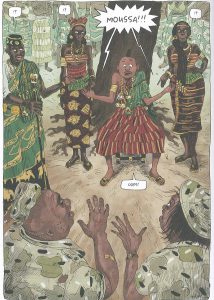

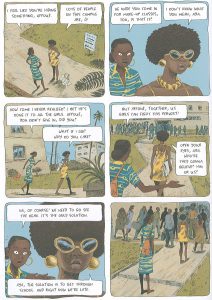

Abouet is a master of plot: the pace runs faster than the Biff! Bam! Pow! of a traditional superhero comic. But while these storylines are rife with sight gags and exclamatory “zoinks” bubbles that give sections of the book a “Scooby Doo” feel (see below), they’re much more serious than they first appear—appropriate, I’d argue, for a book that claims to be about “love.” The character Innocent, for example—visually, a “Thriller”-era Michael Jackson clone—helps his new Parisian boyfriend, Sébastien, simultaneously come out to his family and hold them together while Sébastien’s mother is still unconscious in the hospital after a heart attack.

This juxtaposition of the ridiculous with the serious helps immerse Western readers gradually into a likely unfamiliar world. The plot lines specific to the Ivory Coast subtly address the wide-ranging effects of modernization on class, gender, race and other weighty issues. For example, Aya, the most ambitious character in the village, and the “modern girl” namesake of the whole series, while making her way through college to become a doctor is threatened with a failing grade by a predatory professor. When Aya resists his advances, rumors start to circulate about her on campus. Another female classmate tells her on the way to class, “When it comes to decent grades, we all do what we can.”

Another rich storyline addresses Félicité, the maid for Aya’s family, but also one of Aya’s best and oldest friends, since the family adopted her when they both were children. In the last book of the series, Aya helped Féli win a beauty contest. When Féli’s father—who originally sold Féli to Aya’s family—hears from a friend who saw her on a billboard, he decides that if Feli is so rich and successful, he wants her back with him in his remote village—whether she wants to come or not.

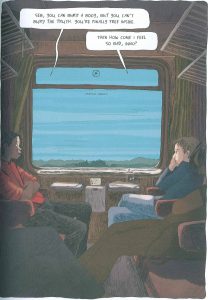

Snapshots such as this illustrate the best that the genre of international comics can do. As with a film, images—gorgeous images in many cases—give you a visual taste of the location, but the “gutters,” the spaces between the frames, suggest two crucial differences. First, they remind the reader of her or his critical distance and visitor status in this likely foreign land. The gutters also, however, make the reader a closer participant in the action than a film would, as the reader works to fill in the spaces between those frames. This ideal critical distance makes the reader a participant in the action more than a novel about the Ivory Coast might, but maintains that participatory status in a way that a traditional plot-based film might not: when you read “Aya,” you’re not a passive theatergoer letting “exotic” representations of the Ivory Coast wash over you. Oubrerie’s rich but still images keep you thinking—even about your own role in this story from your faraway, likely Western, reader’s perch.

Am I taking this argument too far? As an unabashed evangelist of this genre, I very well might be—but read it yourself. I’d love to hear what you think. In the meantime, you can try out one of the recipes from the appendix of the book, which also includes a glossary and short essays explaining the cultural history of the Ivory Coast. My next post will also be food-related, a review of Lucy Knisley’s cooking memoir, “Relish.”