Originally published on GoshenCommons.org March 3, 2014

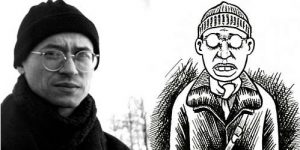

Image from The New Yorker

Joe Sacco is a pioneer—arguably the pioneer—of comics journalism. His 1993 breakthrough work “Palestine” told the story of his visit to the West Bank and Gaza Strip to learn about that area’s conflict directly from its people. This is also the work that introduced most readers to his narrator self, a blank-eyed and somewhat bumbling figure whom readers could easily project themselves into as he attempted to navigate the complicated and competing histories of this war-torn area. Here’s what Sacco really looks like, next to his narrator.

Image from culturalweekly.com

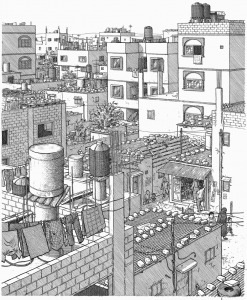

The black and white drawings in “Palestine,” as in all of Sacco’s works, are beautiful, precise and wrenching all at once. The book raised important discussions about the impossibility of pure objectivity when it comes to journalism: by placing himself visually into the story, Sacco acknowledged that this story, politically charged by default, was interpreted and conveyed by one person with one perspective. Yet it was a rare and valuable perspective: Sacco’s research and reporting was meticulous to a fault, as honest and objective as he could make it.

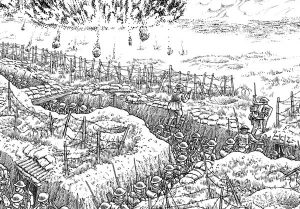

Since “Palestine,” Sacco has continued to win awards for his works about war zones and impoverished areas, from the Balkans to the slums of India to the Occupy Wall Street camps. Here are two images from his 2009 work “Footnotes in Gaza”:

Images from “The Comics Journal” and Mondoweiss.net

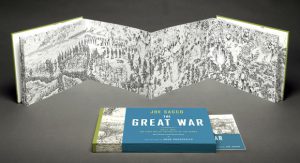

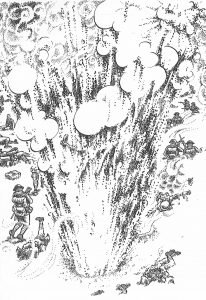

“The Great War” is a surprising topic shift on a number of levels: not only do readers lose Sacco’s narrator and narration—this 24-foot panorama contains no words—but the topic shifts from current conflict to 100-year-old history. Perhaps that explains the work’s overall shift in style, from his usually heavy lines to a slow-motion pointillistic dream.

Image from “The Guardian”

The 1916 Battle of the Somme in France is a “never again” story from World War One, a lesson in how it can take more courage to stop a bad plan already in motion than to barrel ahead, however assured the disaster. As Adam Hochschild explains in his introductory essay, excerpted from his World War I book “To End All Wars,” British artillery bombed the German front lines for a week before the battle, a “shock and awe” tactic that was supposed to clear the way for British soldiers to sweep in and occupy the territory. It was clear even right before whistles marked the start of the offensive at 7:30 a.m. on July 1 that the bombs hadn’t worked as expected, but the war machine was already humming along, unstoppable. This makes the first frame of the advance especially chilling, as one of the British officers climbs out of his trench armed with nothing but a handgun.

Image from “The New York Times”

“The week-long bombardment,” writes Hochschild, “had been impressive mainly for its noise.” Almost 20,000 British troops were killed within the first hour of the advance, and over 57,000 were killed or hurt by the end of that first day. The Germans had simply left the trenches during the bombing, then returned to pick off the British soldiers with machine guns and other weapons as they approached. A full week of bombing hadn’t even opened holes in the German barbed wire, because as Hochschild notes, shells that normally exploded upon impact would have had to explode midair, right at the level the wire was hung.

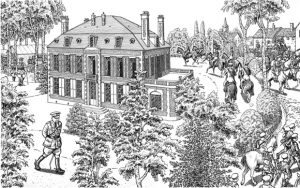

Sacco’s research for this project was extensive, as careful and detailed as you would expect from an acclaimed historian. In a recent “Slate” article, Sacco adds extra annotations to a single page of the published work (the original booklet contains 49 for the whole panorama), and discusses in his explanation of this image

Image from Slate.com

how time-consuming it was to draw 100-year-old history accurately. He spent hours in archives, looking especially for photos of the same visual artifacts from different angles. To draw this piece of artillery correctly, he watched You Tube videos to see “how far back the barrel went after each shot,” and where the soldiers stood to load and fire. If only the British commanders had researched as carefully as Sacco.

“The army was a single organism,” Sacco explains in his introductory author’s note, yet most brilliant about this work is the way he emphasizes simultaneously that that these men are all individuals, that they could too easily be us. The individual faces from before and after the offensive are particularly striking.

Images from W.W. Norton and Slate.com

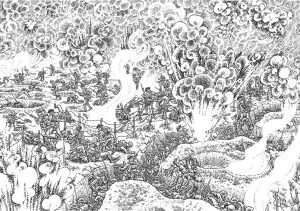

And of course there’s the battle itself. No color means no gore when a body is blasted open, but we do see a curl of heat? smoke? a soul? traveling up from the opened guts of that soldier on the bottom right.

In color, the entire work would have been bathed in red and its accompanying shades of carnage, but of course the World War I archives Sacco researched are also in black and white. Sacco expertly harnesses the simplicity of pen and ink, gathering his troops in a slow dance as the battle quite literally unfolds. The guts and explosions are pixellated on the battlefield, obscured by smoke or dust, the effect like encroaching television snow.

This debacle has become the stuff of sad legend, and Sacco’s style also conveys that dim film of hindsight and history in the panorama’s hazy, dreamy representation of time and scale: we see, for example, British commander in chief General Haig three times in the first panel, as he mentally prepares himself for the battle—which, as he wrote to his wife days before the attack, he felt was planned “with the Divine help”:

Image from The 9th Blog

Many words have been spilled in attempts to analyze this day, this battle, and its staggering carnage. Rather than try to explain yet again, Sacco gathers his readers for a moment of silence.

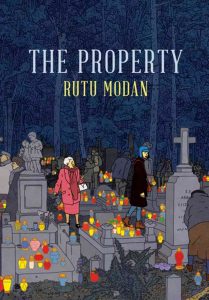

Next post, we’ll jump to a story spun out of World War II. We’ll return to both color and words with “The Property” by Israeli artist Rutu Modan.

Thanks to Better World Books in Goshen, Indiana for supporting this blog and for supplying Michiana with the good reading to get us all through this interminable winter. Keep the comments and suggestions coming, and see you in two weeks.