Another lost post from the Elkhart Truth archives: this is one of my favorites. Check out the video links at the bottom if you don’t have time to read the whole thing. Enjoy your holidays, all, and stay tuned for more reviews in 2018!

Thanks to Better World Books, 215 S. Main St. in Goshen, for providing me with books to review. You can find all of the books I review at the store.

When veteran animator and illustrator R.O. Blechman graduated from high school, his art teacher refused to write him a recommendation. As Blechman told Jeet Heer in a 2011 interview in “The Comics Journal,” “She basically said ‘Look, I can’t say anything good about you, and I won’t say anything bad about you so I won’t say anything.’”

Blechman and his now-signature wobbly lines probably didn’t translate very well to traditional high school art assignments. Fortunately, his professors at Oberlin College encouraged him to develop his own style, however idiosyncratic. When he graduated and got his first break—to write a Christmas story for the publisher Henry Holt—he chose a simple story to match his simple illustrations, and drew up a manuscript in a single night.

“The Juggler of Our Lady,” originally published in 1953 and re-released by Dover Books in a 2015 reprint, retells the 1892 Anatole France version of a classic medieval legend about a juggler—read: young artist—trying to find his place and purpose in a violent, distracted, and unkind society. Cantalbert practices his craft every day despite his lack of an audience, and dreams of the ways that juggling, which makes him so happy, might inspire social reform.

In an introduction from 1980, Maurice Sendak asserts that this book marks Blechman as a pioneer of the “graphic novel” well before the term existed, but Blechman himself called the book a “picture story ” in a 2007 interview for Animation World Network.

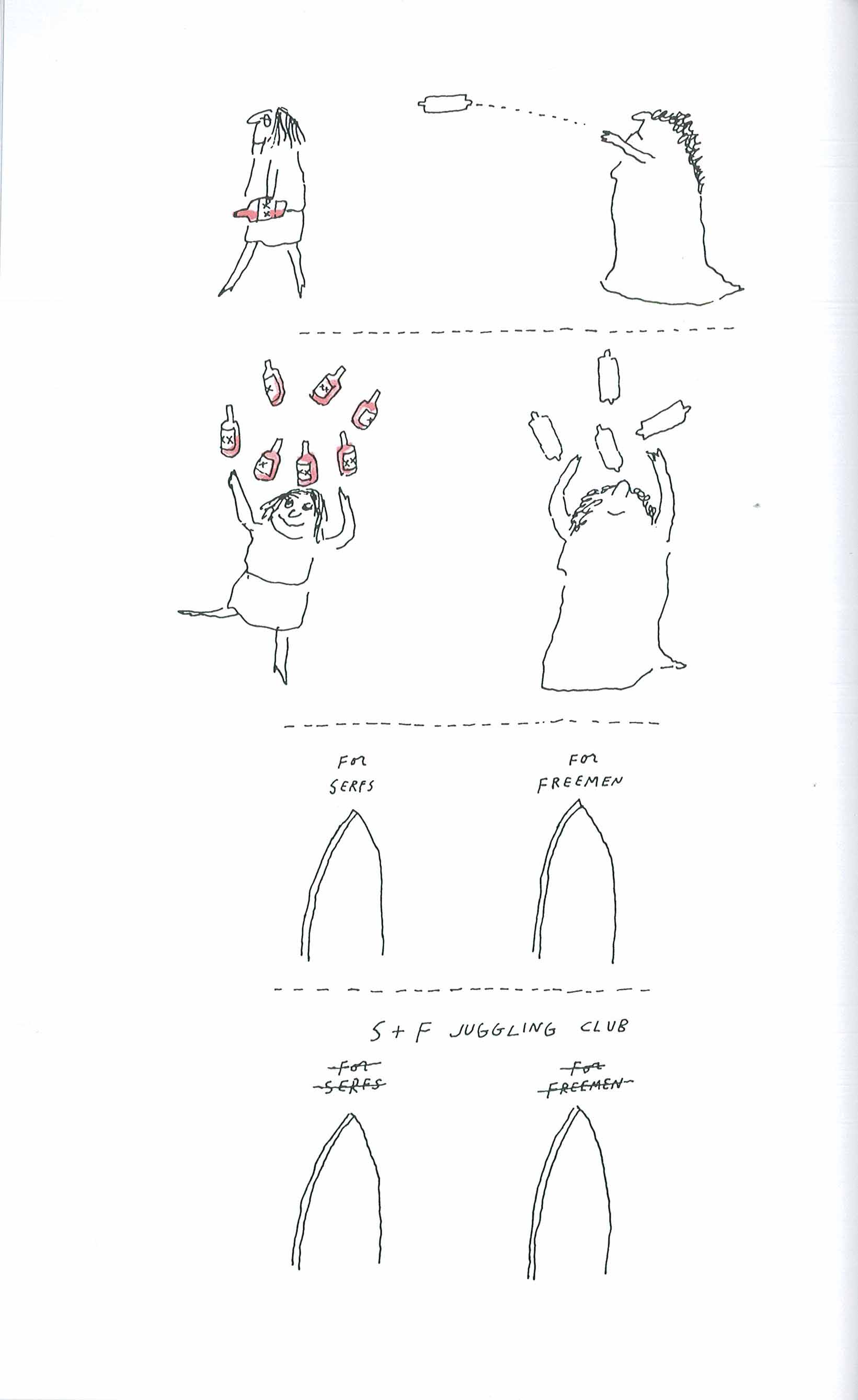

The following two pages, for example, might not have the frames that mark a comic or graphic narrative for most of us, but still achieve the multilayered storytelling that readers of the genre expect. Cantalbert, frustrated by his lack of a fan-base, attempts a more socially recognizable and acceptable vocation than juggling.

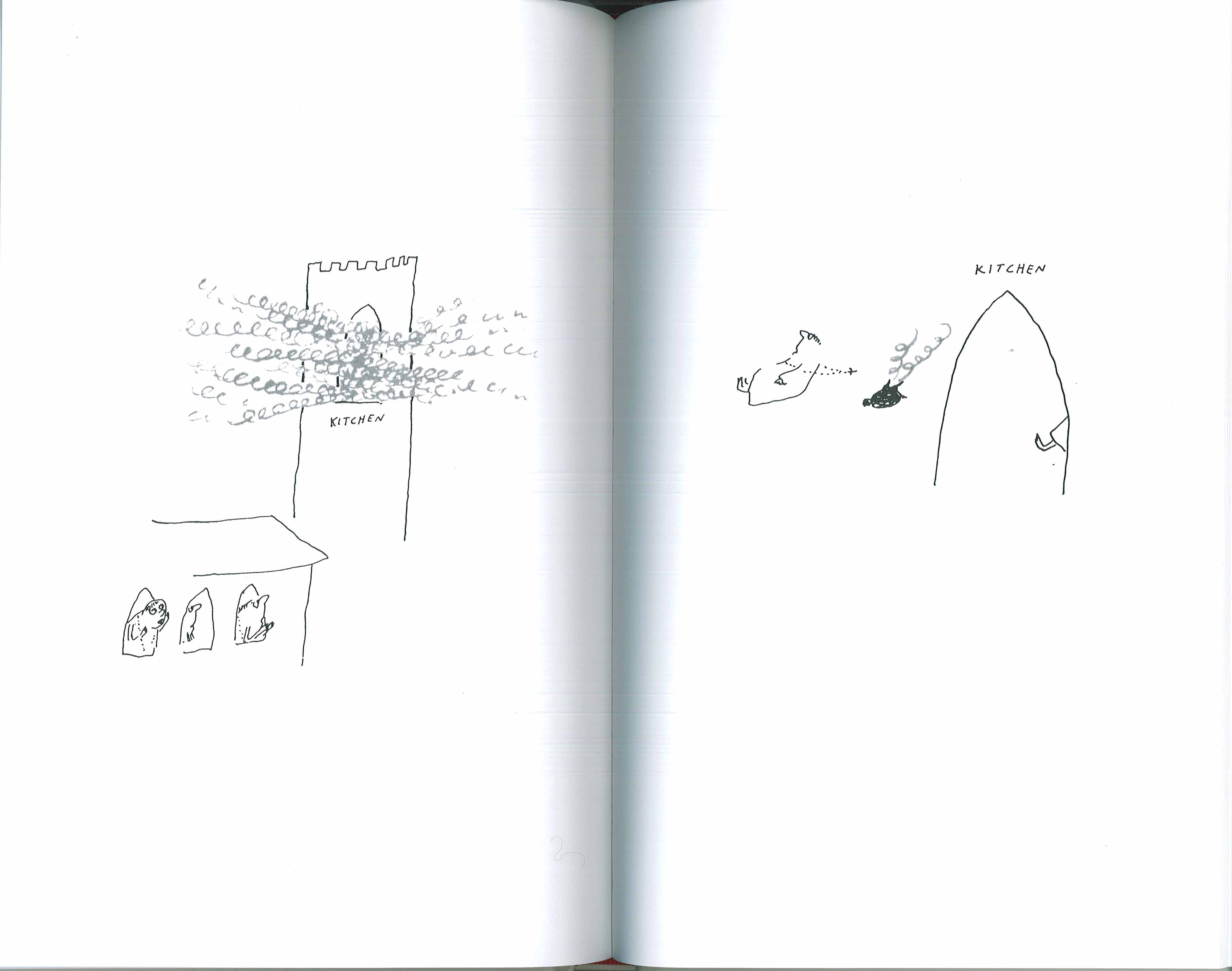

Cantalbert tries and fails not only at cooking, but at poetry, music, sculpture, and painting, echoing a basic story retold many times over from “The Little Drummer Boy” through centuries of children’s books.

But what catapults this book from cliche to masterpiece is the density of action and sensory information contained within so few lines and squiggles—and dots, for that matter, as the beads of his rosary hover just above the charred goose soaring behind him. We feel the heat, smell the smoke, and hear the whispering of the monks. Our childhood cartoons—also prefigured by Blechman’s early work in animation—have trained us to hear the projectiles’ whistling descent and to picture a couple of bumps and a skid for the landing. We’re so well trained, in fact, that Blechman doesn’t need to draw the landing or Cantalbert’s likely “oomph.”

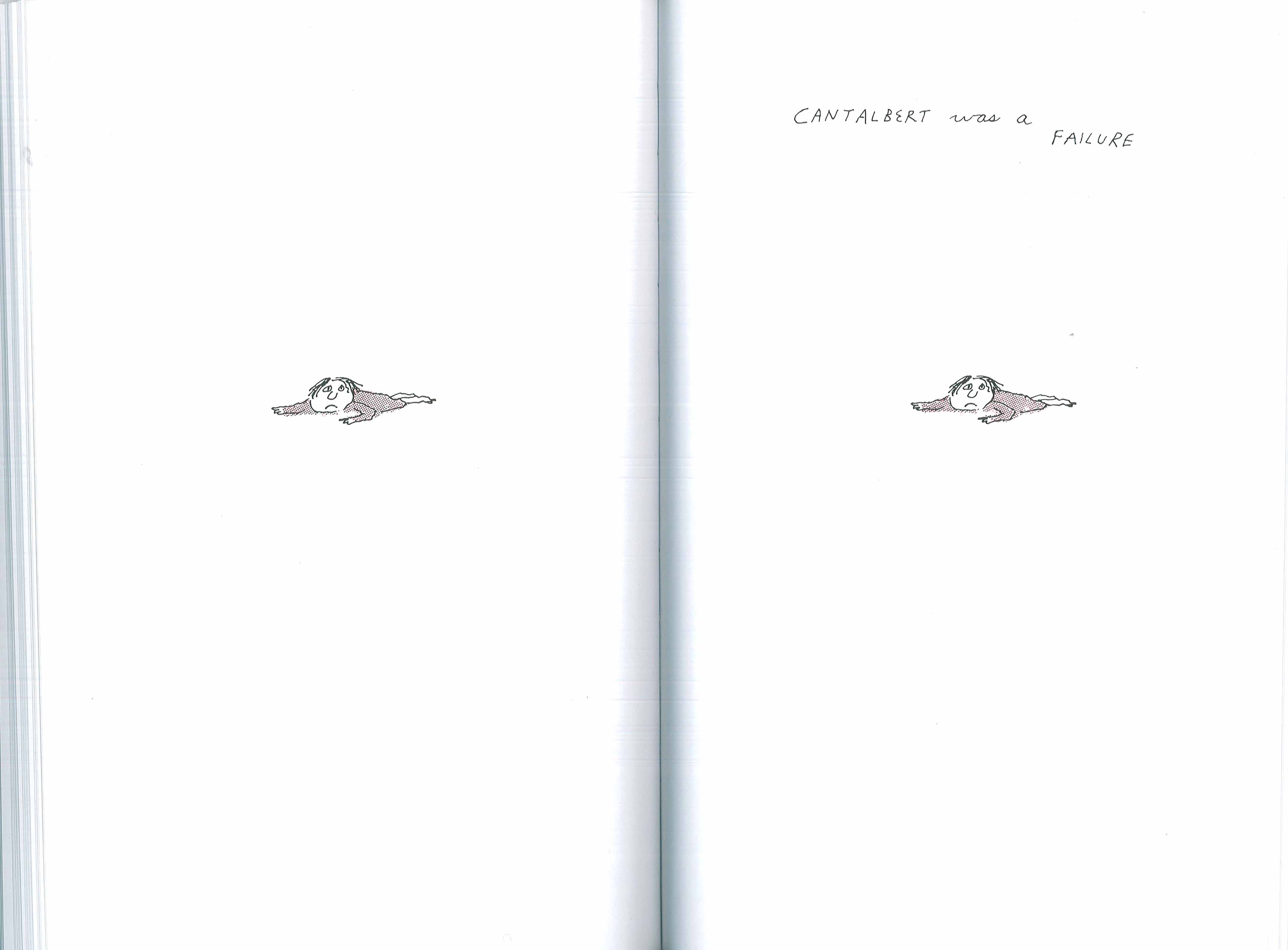

Master of white space, Blechman doesn’t need to waste ink on frames, or even on a line for the ground that Cantalbert falls on when some pranksters knock him over during a performance in the town square.

Blechman manipulates space so well that Cantalbert doesn’t look like he’s floating: we can see the invisible ground that his body has flattened to meet. Clearly it hurts, both physically and psychologically—and metaphorically, too. Blechman reminds his readers of the difference between the beauty of simplicity and the brutality of the McCarthy-era oversimplification in which his book was first released, and amidst which he saw many artists around him blacklisted.

What connects all of Blechman’s art, from his 1970s political cartoons protesting the Vietnam War, to his animated features, to even his commercial work (he’s especially famous for a 1967 Alka Seltzer ad) is his quiet advocacy for compassion and reconciliation—something we could all use amidst turbulent times. I leave you with his 1966 Christmas cartoon for CBS. Peace.