This review first ran in the “Elkhart Truth” in April 2015.

Thanks to Better World Books, 215 S. Main St. in Goshen, for providing me with books to review. You can find all of these books at the store.

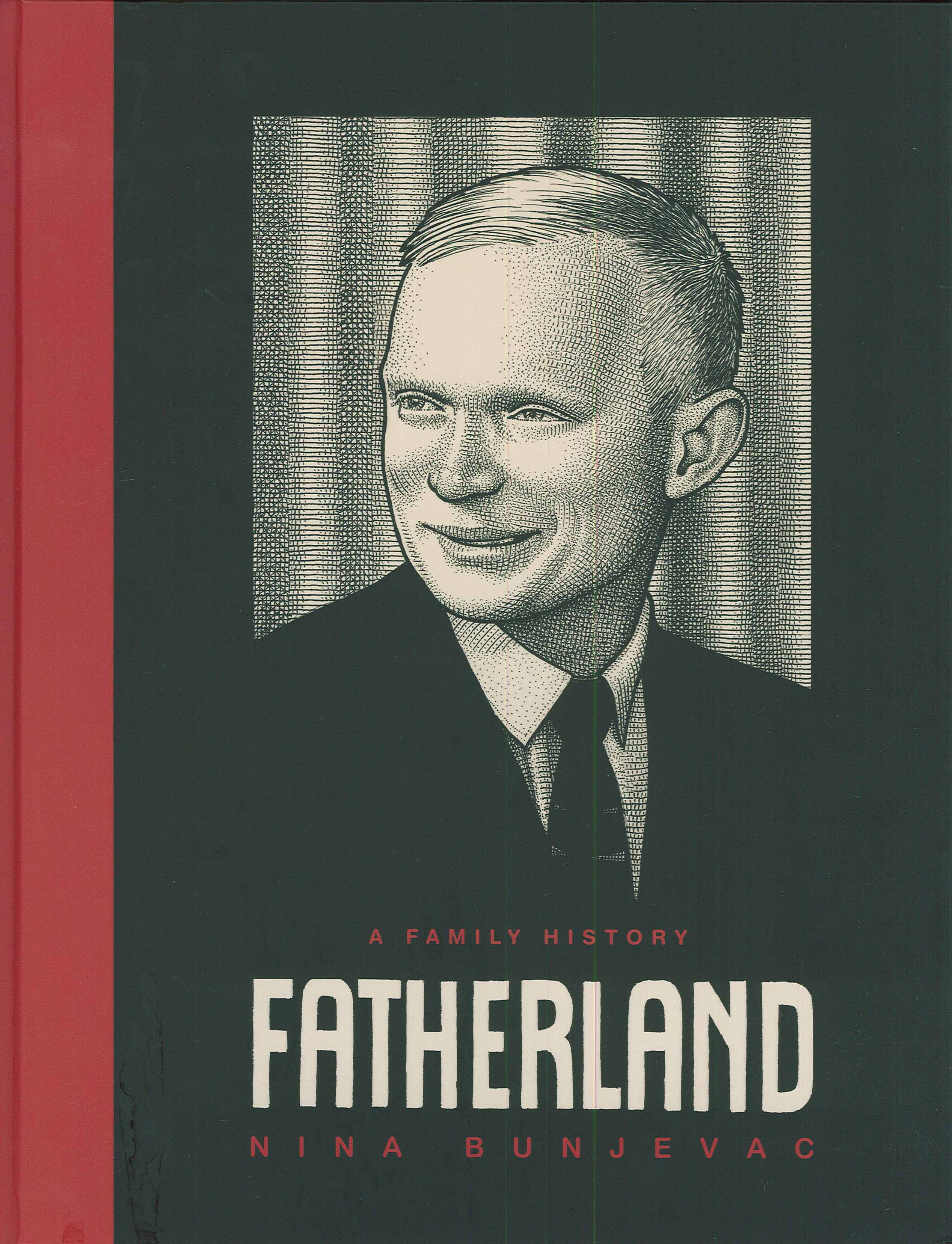

Nina Bunjevac’s “Fatherland” is about many things, some quite difficult, some—like the history of the former Yugoslavia—quite dense. At root, this story is about a young girl losing a father she barely knew. Peter Bunjevac, a Serbian nationalist, died in a garage explosion in 1977 in his adopted country of Canada. No one knows exactly what happened, but he was likely assembling bombs. His daughter Nina was preschool age at the time, living in Yugoslavia with her mother, sister, and grandparents.

Now in her forties and living in Toronto, Bunjevac understands a lot more, both about the history of the region that her parents came from—now Croatia—and about the politics behind the Serbian loyalist terrorist organization with which her father became entangled.

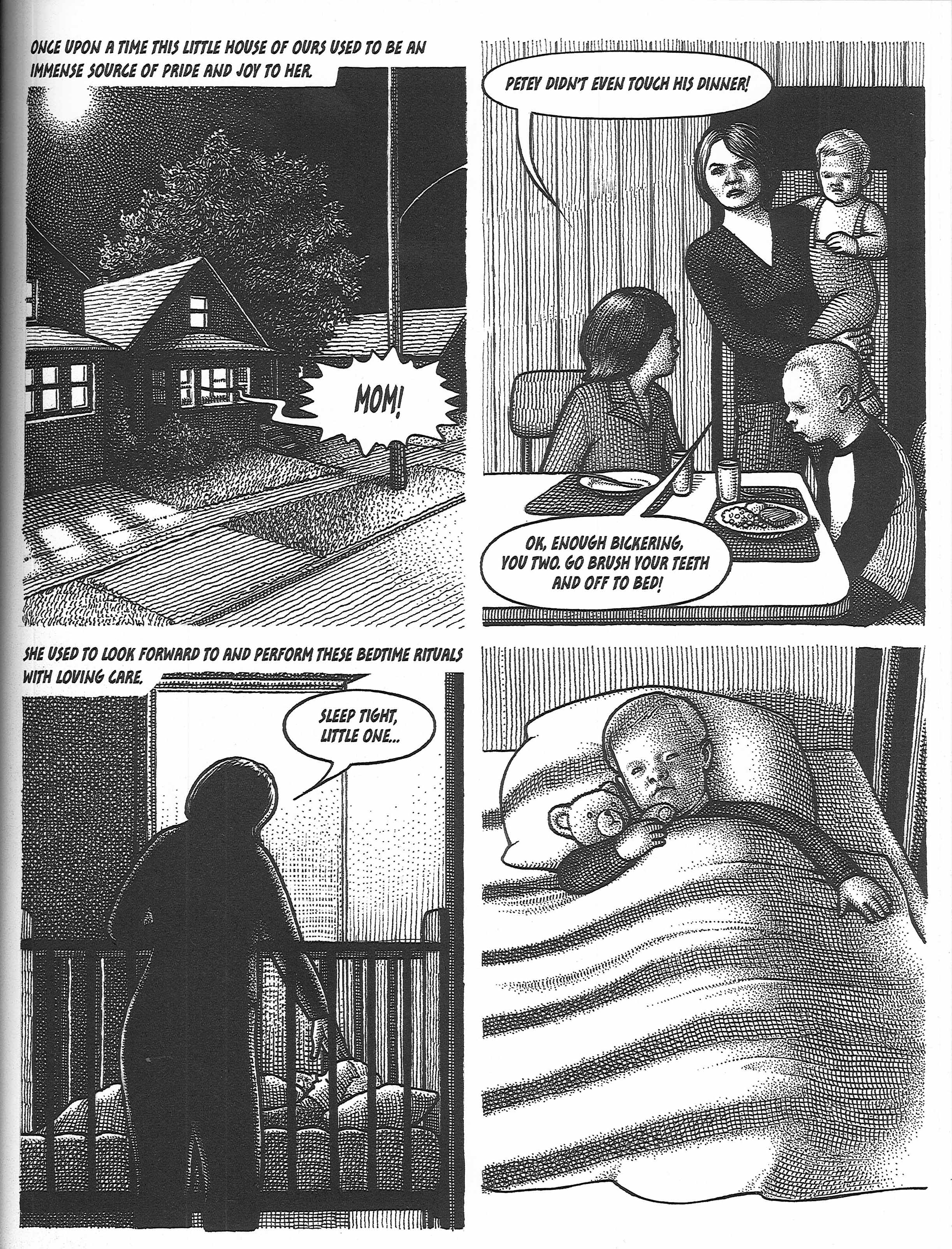

In the early 70s, Bunjevac’s family was living in Welland, Ontario. Her mother would get suspicious when her father stayed out late, but not for the reasons that usually crop up in a marriage (drinking, gambling, or having an affair). One morning when Bunjevac’s father is supposedly on an “overnight trip,” her mother hears headlines on the morning news about an explosion in a Croatian community center, and realizes that her husband was involved. She resolves to take her children back to Yugoslavia to live with her parents. In the most heart-wrenching decision of her life, when her husband insists that her son Petey stay behind, she leaves father and son together so that she and her daughters can escape.

Bunjevac grew up with no recollection of her father or of Canada. Her grandparents were Communist partisans, political polar opposites of her father. As she told a National Public Radio interviewer in January, “Once I started discovering more and more, . . . I realized that his ideology was exactly responsible for the dissolution of the country that I had lived in, and that brought a shock to me. I was very resentful for a long time.”

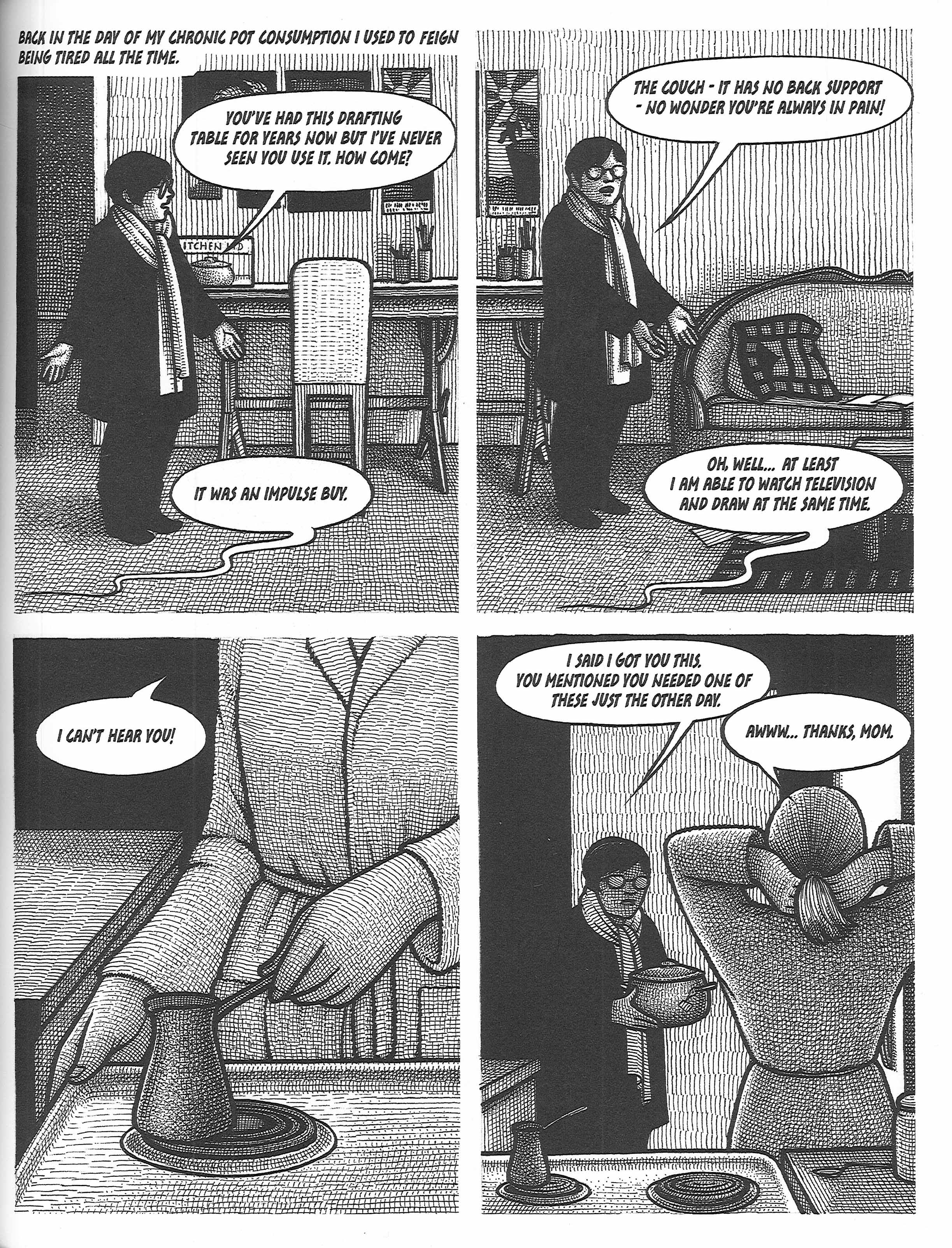

The history of Bunjevac’s family and nation would be heavy for anyone, child or adult, and her illustrations reflect that weight. Her figures are thick, obsessively dotted and crosshatched, making Bunjevac and her whole family look stiff-limbed, like refugees carrying multiple layers of clothing on their bodies instead of in suitcases.

Despite the paternal emphasis of the book’s title, this story is also about Bunjevac trying to make sense of her mom: how she could have ended up with a person like her father, how she could leave her son behind, how she struggled through and made sense of her life, a life in which she still can’t walk away from her daughter’s apartment until she hears the click of the lock behind her.

Despite the paternal emphasis of the book’s title, this story is also about Bunjevac trying to make sense of her mom: how she could have ended up with a person like her father, how she could leave her son behind, how she struggled through and made sense of her life, a life in which she still can’t walk away from her daughter’s apartment until she hears the click of the lock behind her.

Bunjevac circles around moments, and especially images, the way a grieving mind circles around any traumatic event. We see her childhood house, for example (top left below), multiple times, from multiple angles.

This was the last house Bunjevac’s nuclear family lived in together, and its visual repetition creates the impression that she’s holding its memory up like a crystal, slowly turning it in the light to look for any new angles, any new shoots of color that might illuminate and help her make better sense of her family’s story.

Readers also see the history of the western Balkans from multiple angles. In the middle section of the book, Bunjevac juxtaposes maps and military leaders with stories of her young parents and grandparents, her structure and style heavily influenced by graphic journalist and historian Joe Sacco. Both Sacco and Bunjevac contrast intense, precise historical detail with personal narratives of individuals struggling to survive. (See my review of Sacco’s “The Great War” here.)

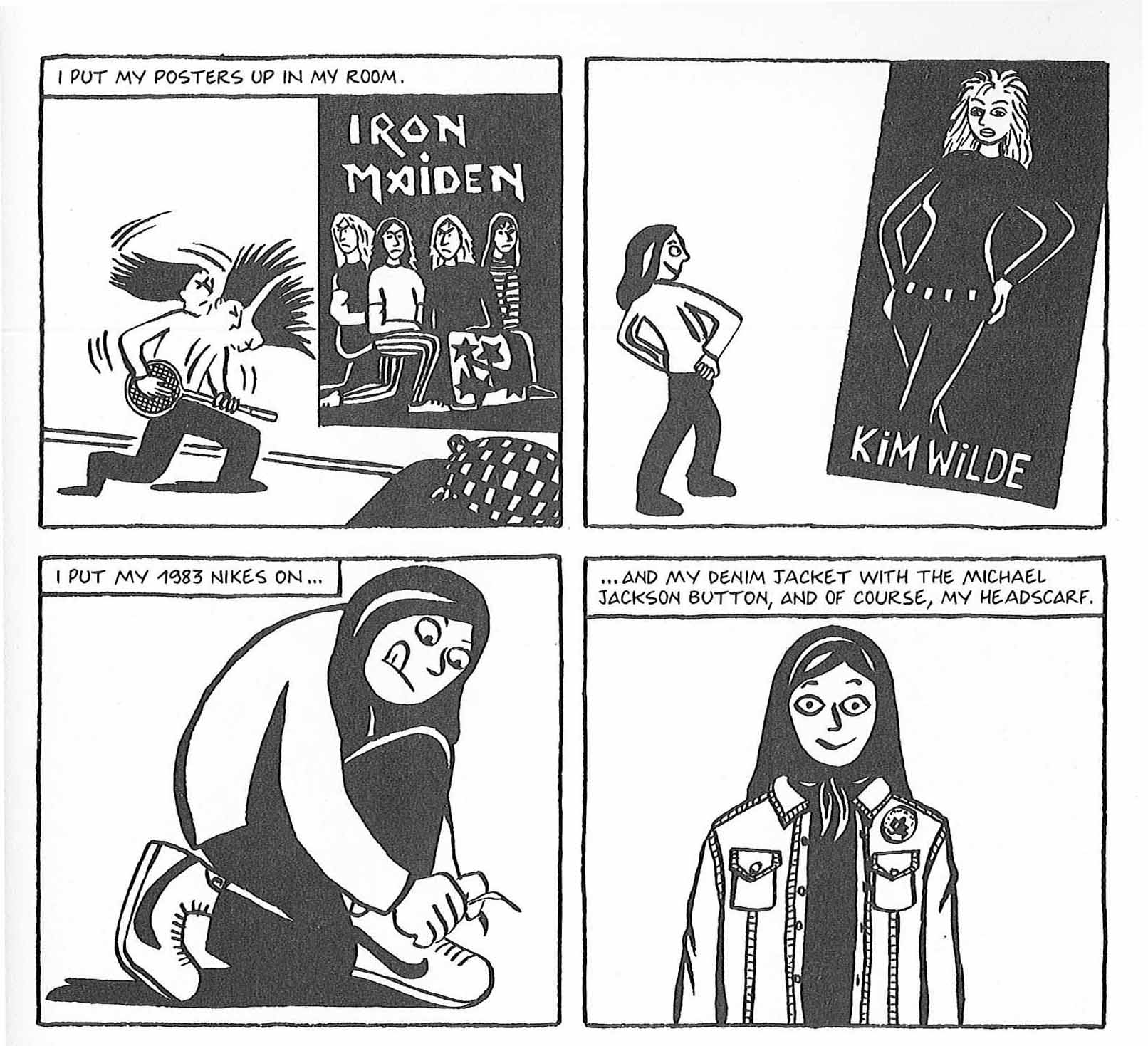

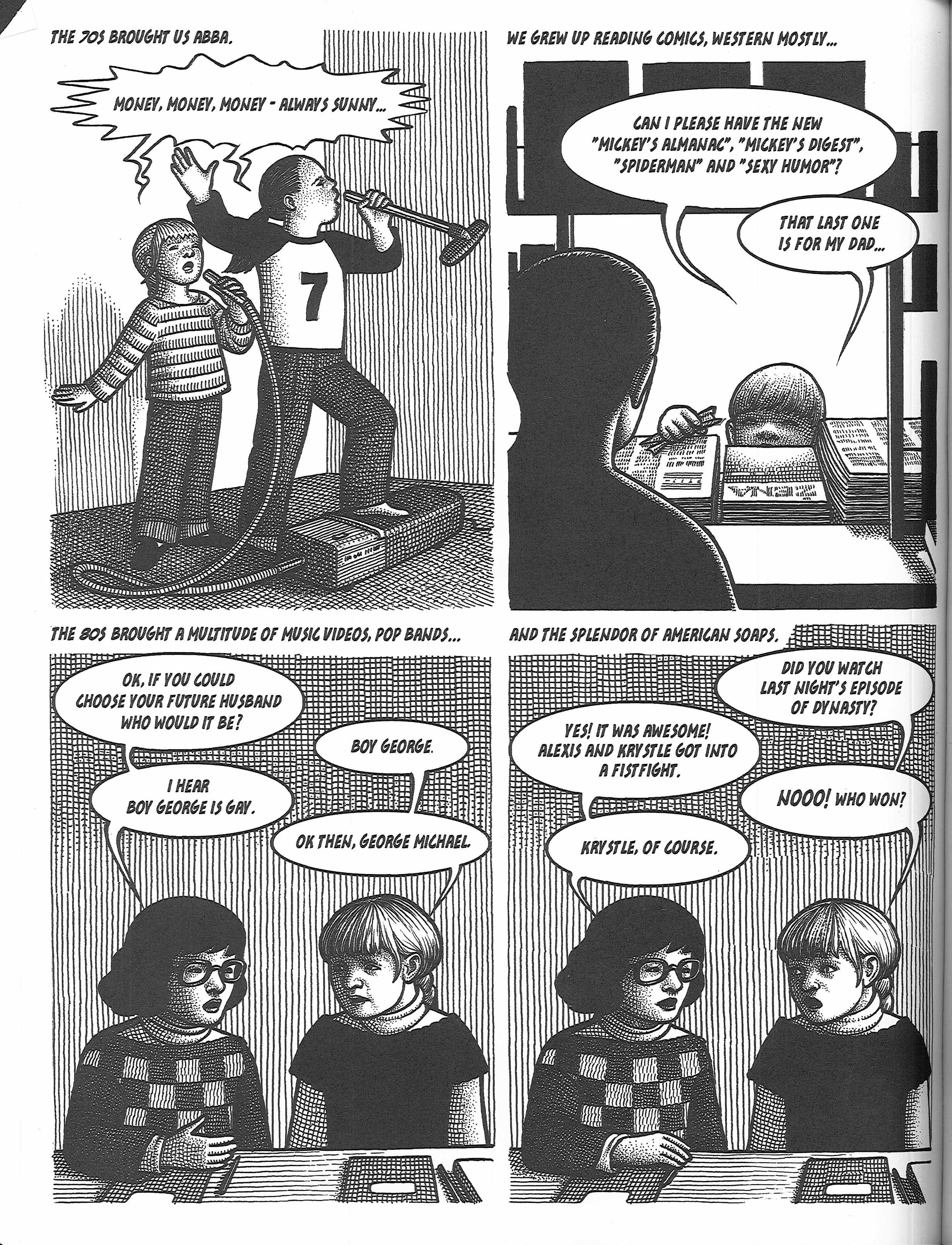

Thematically if not visually, “Fatherland” also echoes the work of Marjane Satrapi, whose 2004 “Persepolis” uses her family history to humanize the history of Iran, and allows Western readers to learn about her nation alongside a young version of herself. These works stress how kids are kids, whether growing up amid dangerous geopolitical conflict, Western media saturation, or both. Here’s Satrapi in 80s Iran,

and here’s Bunjevac and her older sister in the Yugoslavia of the 70s and 80s:

A less obvious influence than Sacco and Satrapi is humorist David Sedaris. As Bunjevac told a writer for “ArtReview” magazine in 2012, when “Fatherland” was in its early development, “As for the format of my new book, I must say that the major influence was David Sedaris. This man has told some pretty heavy stories disguised through humour and wit.”

But what really elevates “Fatherland” from notable book to masterpiece is the simplicity of the ending. After such visual and historical weight and density, a simple yet convincing ending is no mean feat. I’ve read many powerful and emotionally devastating graphic novels, but none of them has made me cry. I shed a tear, quite literally, at the end of “Fatherland,” surprised by a jolt of improbable hope, of a flash of light and lightness after bearing witness to Bunjevac’s crushing, cyclical, multigenerational tragedy.

“At first I wanted to do a graphic novel about every single crime against humanity committed in the former Yugoslavia,” said Bunjevac, discussing the origins of “Fatherland” in her “ArtReview” interview. But after visiting Croatia in 2012 to participate in a workshop sponsored by the Centre for Peace Studies, she explained, “I decided not to write about things I have not experienced. Reconciliation needs to be brought to the generation responsible for the terrible things that happened in the 1990s, but peace-building is up to the new generation, who are more likely to read comics.” As Bunjevac said of her fellow workshop participants—artists, writers, and activists all from former Yugoslav republics—“Put us together under the same roof and what you get is tears and laughter and nostalgia you could cut with a knife,” a fitting description for “Fatherland” as well.