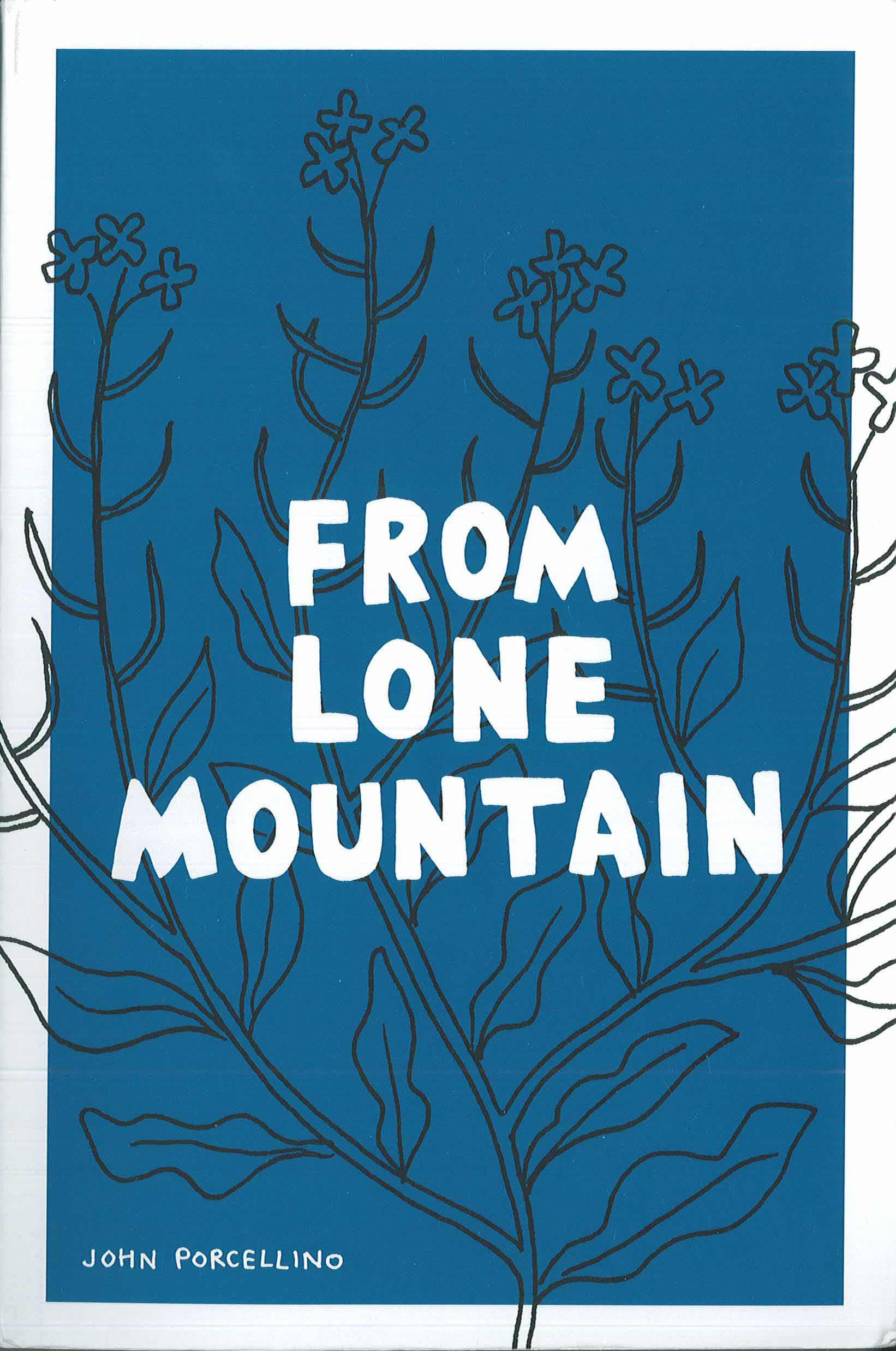

From Lone Mountain, by John Porcellino. 304 pages, Drawn and Quarterly, March 2018. Paperback, 22.95.

NOTE: Drawn and Quarterly sent me a free review copy of this book.

Thanks to Better World Books, 215 S. Main St. in Goshen, for providing me with books to review. You can find or order all of the books I review at the store.

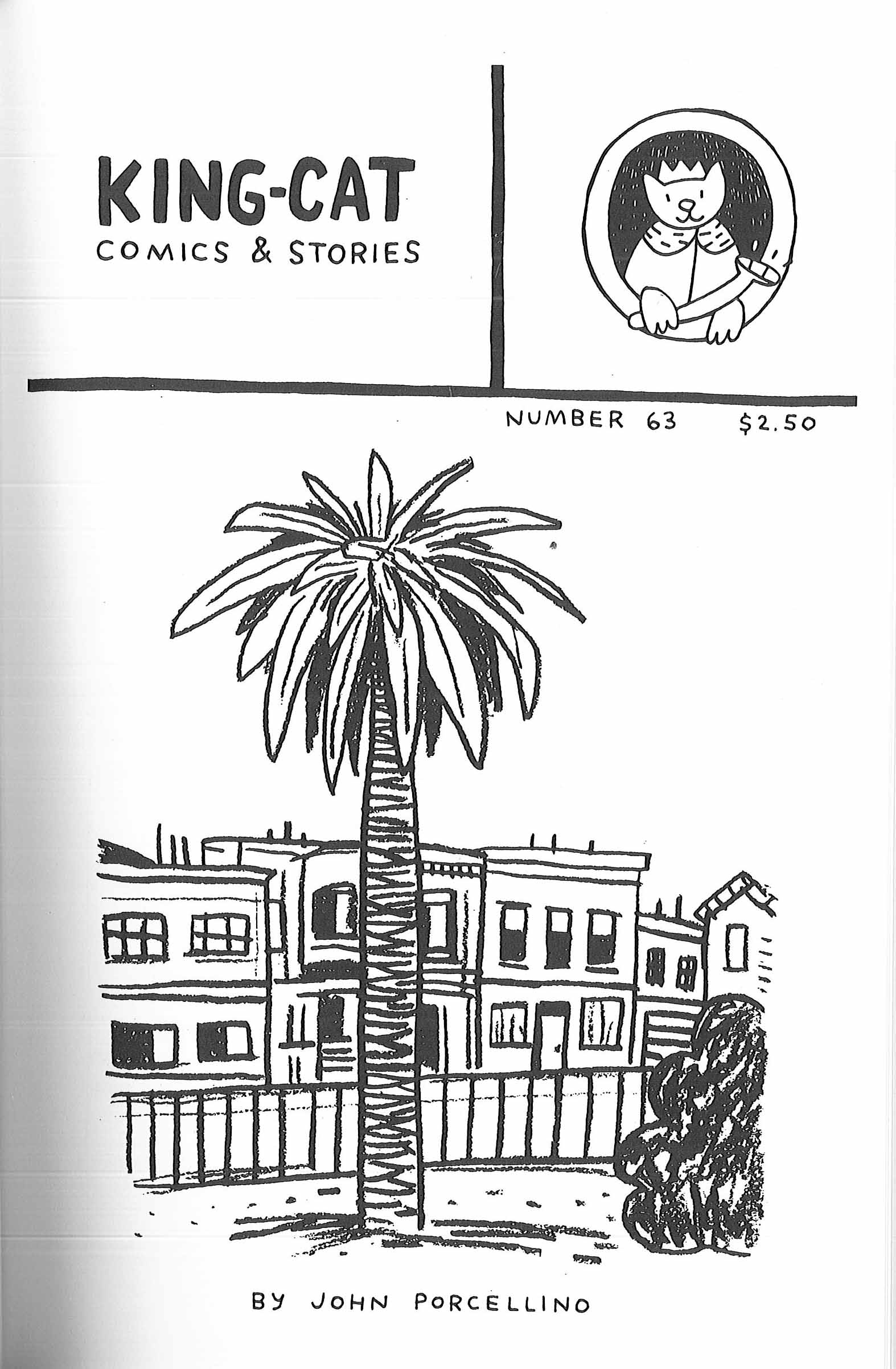

This is King Cat:

![]()

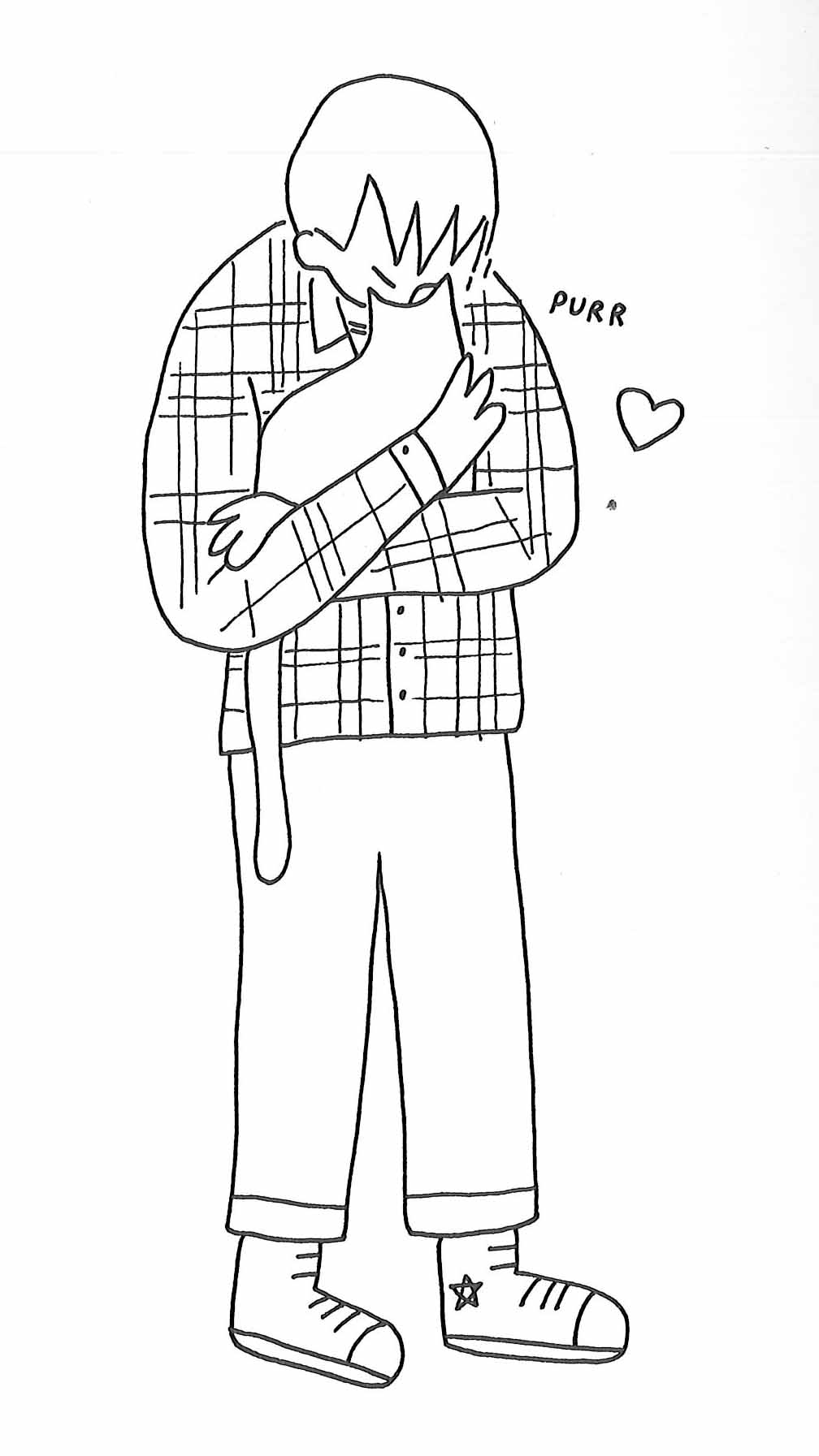

This is his creator, John Porcellino:

Pause for a minute to bury your face in that cat’s fur, to feel that same purr. As long as you don’t suffer from allergies, this is a fair representation of the effect on its readers of the most recent King Cat collection, From Lone Mountain.

King Cat is a zine of comics and stories that Porcellino has been creating and self-publishing since 1989, when he was in his early 20s. The first run of King Cat was fewer than 20 copies, and sold for sixty cents. The zine now goes for five dollars, and you can get a four-issue subscription for twenty bucks at Porcellino’s comics and zine distribution site Spit and a Half.

From Lone Mountain, just released in March by Drawn and Quarterly, collects issues 62 through 68, which were initially published from 2003 through 2007. The book also includes a few outtakes from that time, as well as a couple more recent bonus comics.

For my money, King Cat is one of the best deals in comics. Not only does each issue deliver drawings, stories, and illustrated “top-forty” lists (which rarely add up to forty), it also exudes a calm that seems to transfer from its pages to your fingertips. Seriously. Insurance companies should give health discounts to readers of King Cat. I swear, peace washes over my body and lowers my blood pressure the minute I pick it up. I trust Porcellino’s measured narration to slow me down, to guide me through his world at a more reasonable pace than I’m able to navigate mine.

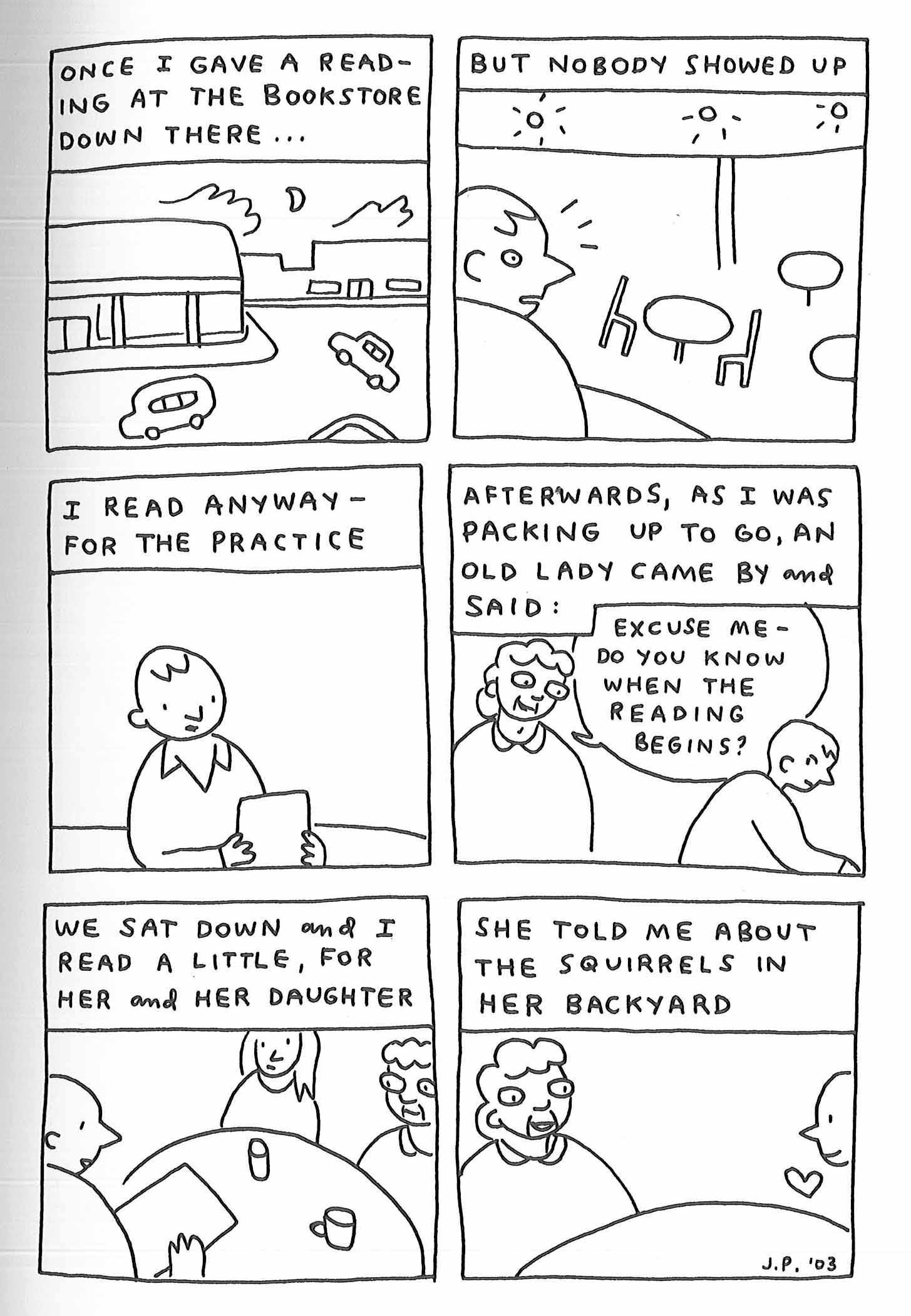

Part of the source of this magical calm is Porcellino’s simple drawings, black lines on a sea of whitespace. Porcellino also seems to weather ups and downs, highs and lows, with ease. Here, for example, he arrives at a bookstore where he’s scheduled to read, but no one shows up. Yet he takes it in stride, delivering his reading to an empty room just “for the practice.” When an audience of two shows up late, the three of them sit down for a while, and talk about squirrels.

That heart in the bottom right corner represents where Porcellino has come in his nearly 30 years of creating King Cat. Many of his early comics bubble with the dark and sometimes biting humor of the punk rock scene of his youth in the 80s. After the 90s brought a major medical crisis, the loss of his father, and continuing struggles with mental health, however, Porcellino has—to put it lightly—mellowed.

Yet from Porcellino’s perspective, his current practice of Zen Buddhism was already nascent in his punk sensibilities. As he recently explained to the Buddhist magazine Lion’s Roar, punk and Zen Buddhism have a lot in common: a DIY aesthetic, as well as an unvarnished view of reality. “Punks find beauty in the forgotten parts of our world—in the concrete underpasses, drainage ditches, and back-alleys. These are all things Zen has taught me, too.”

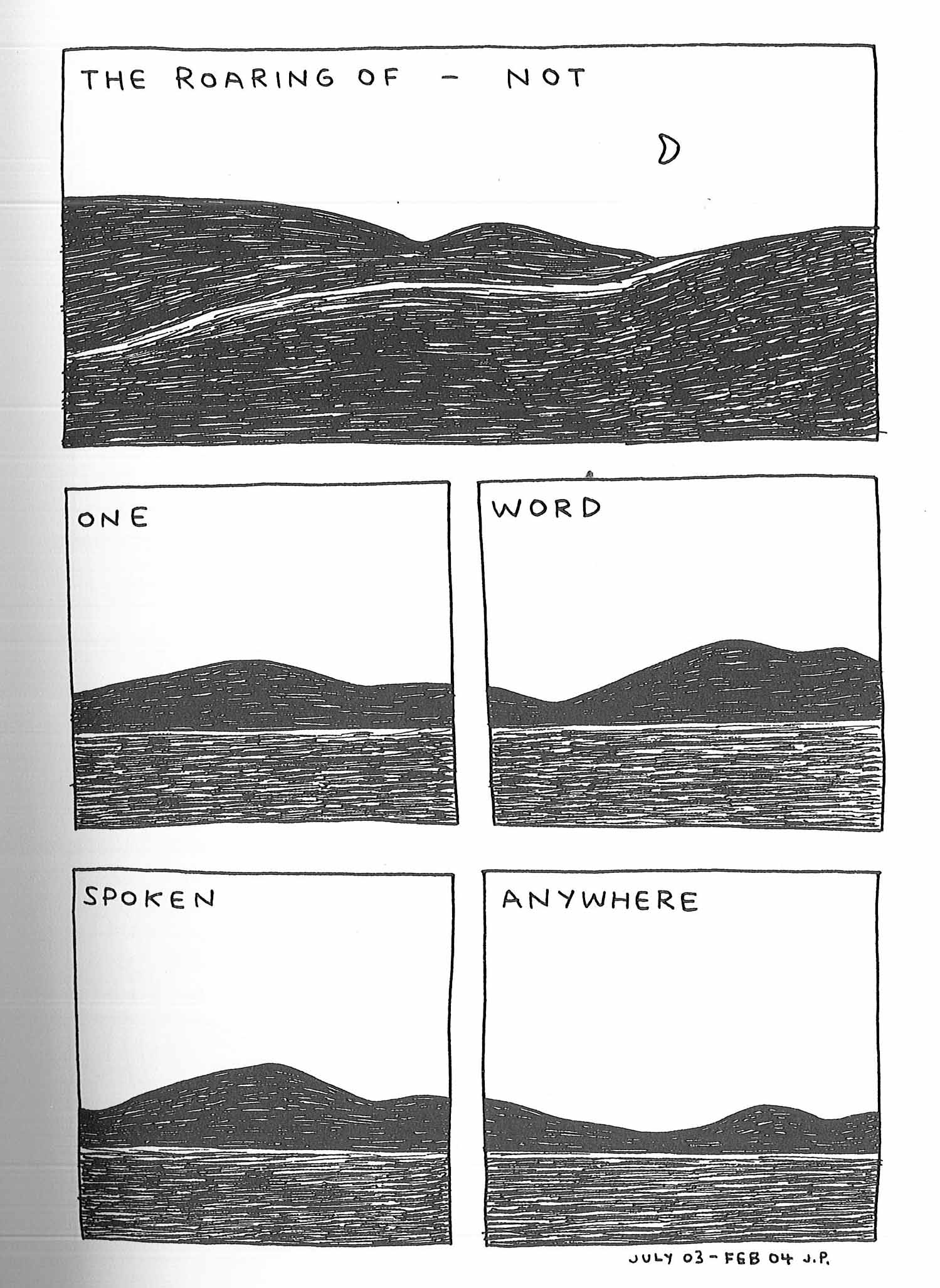

If punk rock and Zen Buddhism don’t seem like an obvious pairing to you, comics and Zen Buddhism might make more sense:

From Lone Mountain also tells stories—a few in prose form rather than comics—about random, rambling road trips and early, seemingly pointless jobs in tiny Midwestern towns. As calming as it is to read, however, Porcellino’s endnotes detail the struggle behind this collection of measured, peaceful drawings. Porcellino had recently recovered from major surgery that saved his life, but his newfound realization of his own vulnerability and mortality—as well as the still recent attacks on September 11, 2001—launched him into a near-paralyzing bout of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

In all of his zines, collections, and books, Porcellino writes and draws and self-publishes his way through both physical and mental illness. His 2014 book The Hospital Suite (also published by Drawn and Quarterly) details his surgery, as well as his mental health challenges both before and after. The issues collected in Lone Mountain overlap with the anxiety he writes about in The Hospital Suite.

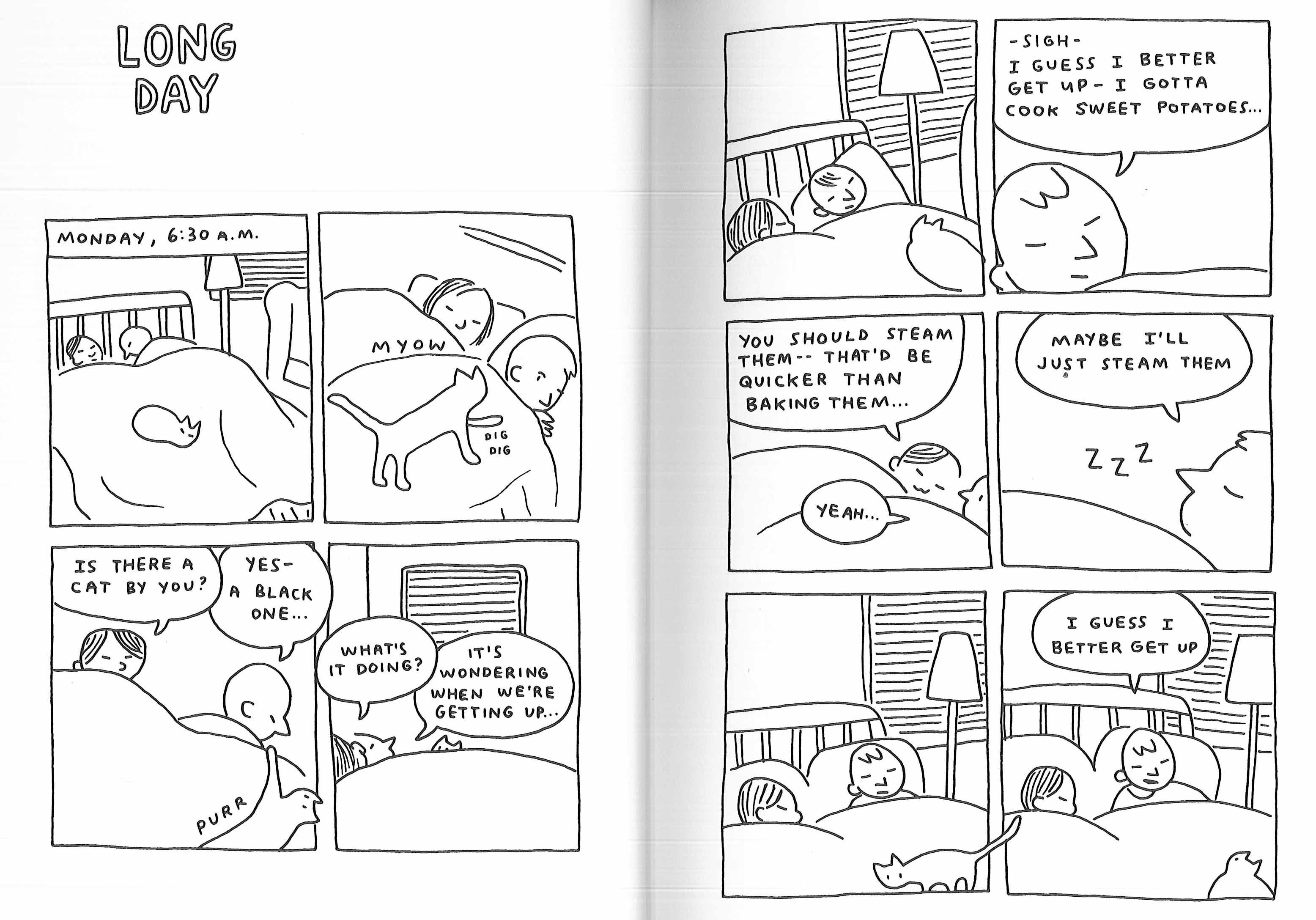

This anxiety rumbles beneath Lone Mountain as Porcellino struggles, for example, with getting out of bed:

But the reigning emotion? Again: Quiet. Calm. Plus humor, as that cat circles the frames, kneading and purring and looking barely a cat, especially when it’s curled up into a potato shape with two ear bumps and two small dots for eyes.

In a 2014 interview with The Comics Journal, Porcellino paraphrased cartoonist Ivan Brunetti, who “always used to say that cartoonists take the whole world, their whole life, and they try to cram it and fit it into these little tiny neat boxes.” The majority of Porcellino’s work is organized into panels, but he consistently reminds his readers that although those black lines are useful organizational tools, they’re permeable, not solid, as the cat’s tail, the narrator’s head, and the word balloons themselves slip out of those boxes in “Long Day” with ease.

Sweet potatoes, touch football, and punk rock coexist in Lone Mountain alongside roads, flowers, skies, and a few Zen koans. Honestly, though, the topics don’t matter as much as the whitespace, pacing, and care with which Porcellino writes and draws his life. It’s fun to note the echoes of two early influences that ran in the Chicago Reader when Porcellino was coming of age: Lynda Barry’s Ernie Pook’s Comeek and Matt Groening’s Life in Hell , a comic strip precursor to The Simpsons. Like the late Harvey Pekar, too, Porcellino chronicles mundane, everyday stories.

Unlike Pekar, however, Porcellino has been perfecting his own illustrations for years. As he told The Comics Journal, “One of my little tidbits of advice I give to younger cartoonists is: Don’t compare yourself to other people. You will always lose that game. There’s always somebody you’re going to crumble in the face of. And you don’t need that as an artist, that pressure and doubt. Your job as an artist is to bring what’s in you out.” From Lone Mountain illustrates in words, pictures, and an excess of peace, that Porcellino has unquestionably come into his own.