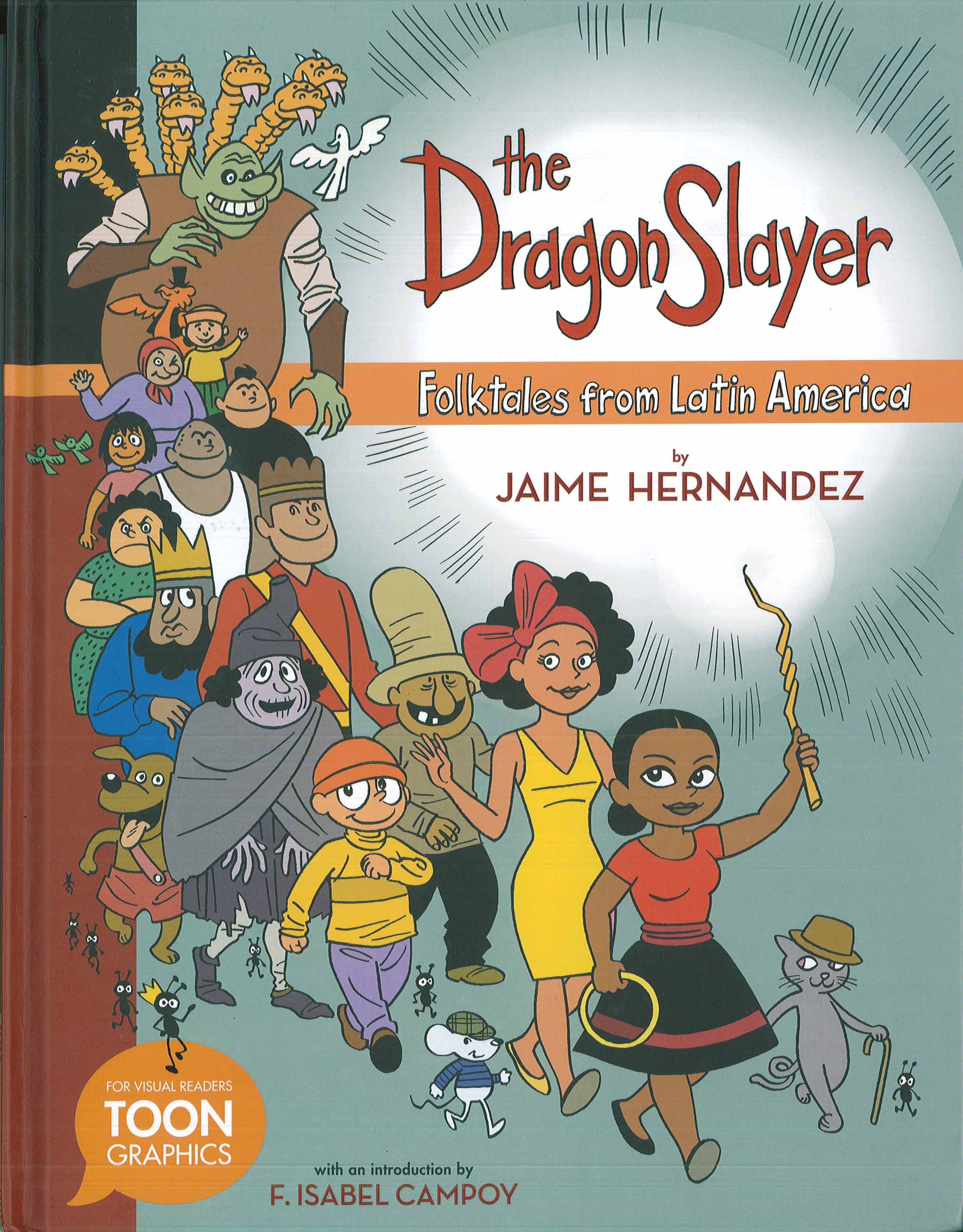

“The Dragon Slayer: Folk Tales from Latin America,” by Jaime Hernandez. TOON Graphics. April 2018. 48 pp. Cloth $16.95, Paper $9.99. Ages 4-10.

Thanks to Better World Books, 215 S. Main St. in Goshen, for providing me with books to review. You can find or order all of the books I review at the store.

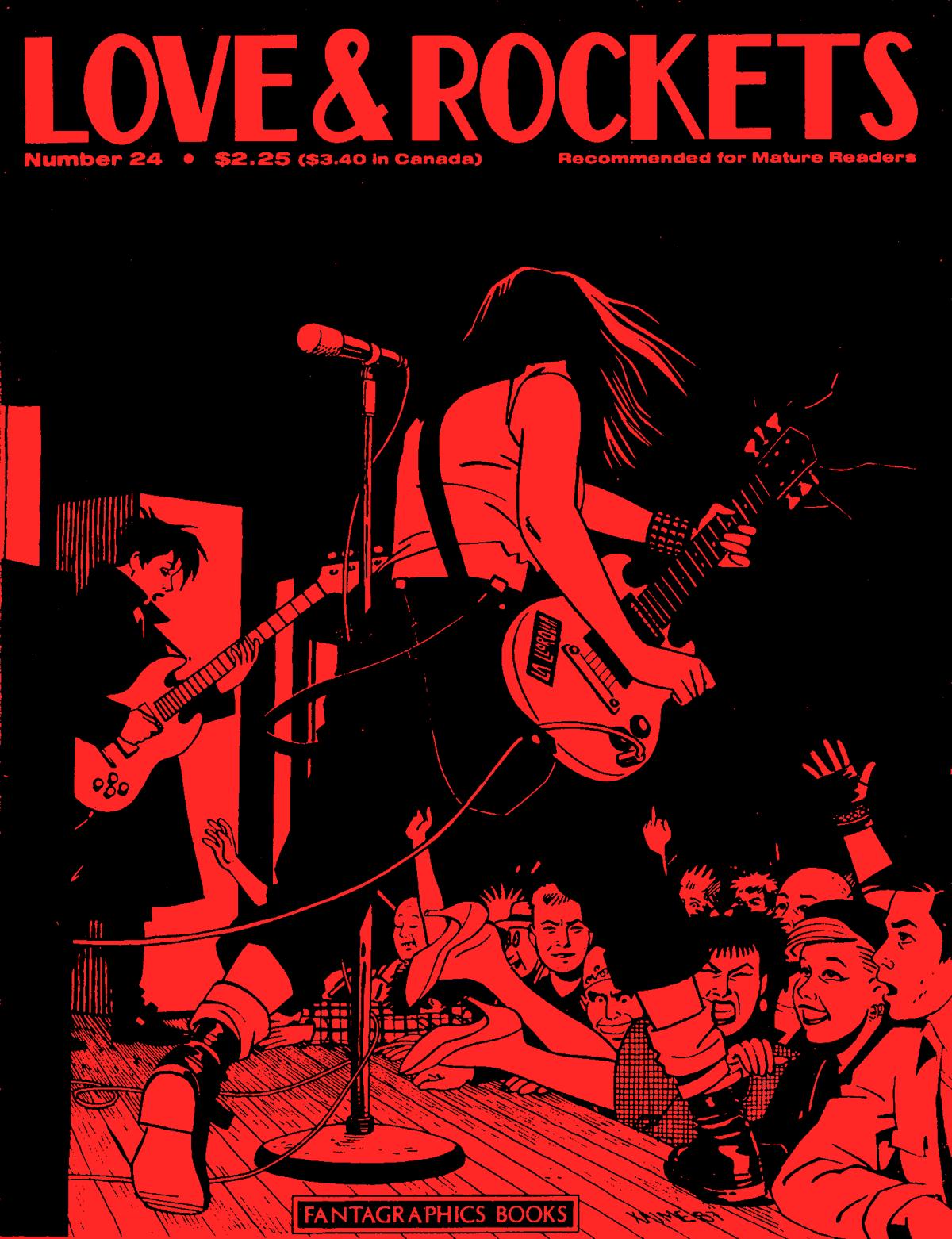

At first it might seem unlikely that Jaime Hernandez, one of the creators of the edgy adult comics series “Love and Rockets,” famous for covers like this:

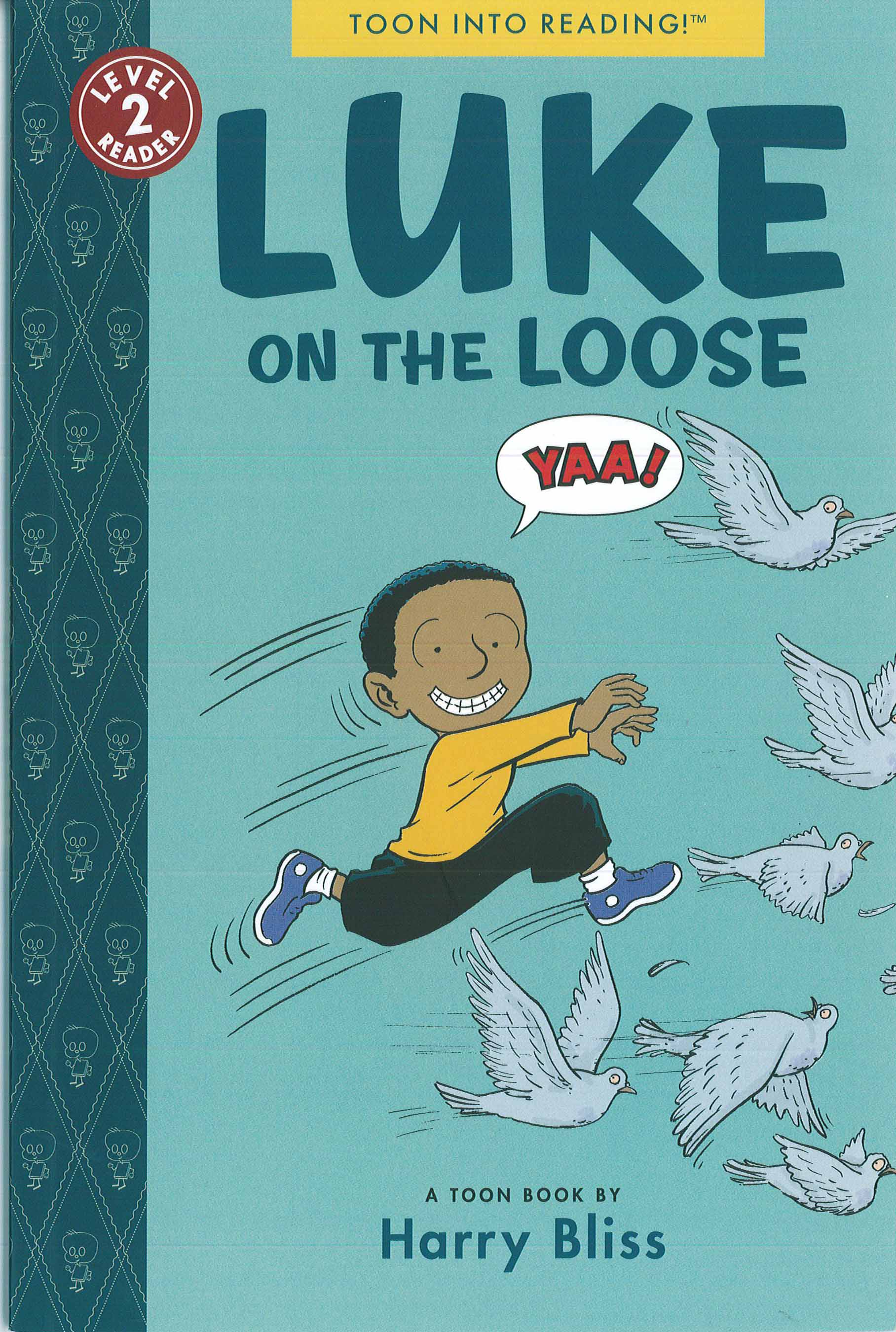

would publish on TOON Graphics, a comics press for kids, famous for covers like this:

It makes more sense, however, than you might think. In the past, Jaime Hernandez’s work has been decidedly NOT for kids, as you can see from the top right of the “Love and Rockets” cover above, and as I made sure to note at the beginning of my review of Hernandez’s “Love Bunglers” a few years back.

With the 1981 inception of “Love and Rockets,” Jaime and his brother Gilbert, two of the three creators of the series (the third brother Mario faded out after a while), helped shape and define the counterculture of comics, as well as music and fashion, from their base in Oxnard, California. They pushed visual boundaries, but with respect: after all, it was their mother who introduced them to comics, so while the female characters may have looked at first glance like top-heavy bimbo stereotypes, once you got to know them, it became clear that they were tough, brilliant, complicated, and—most important—not to be messed with.

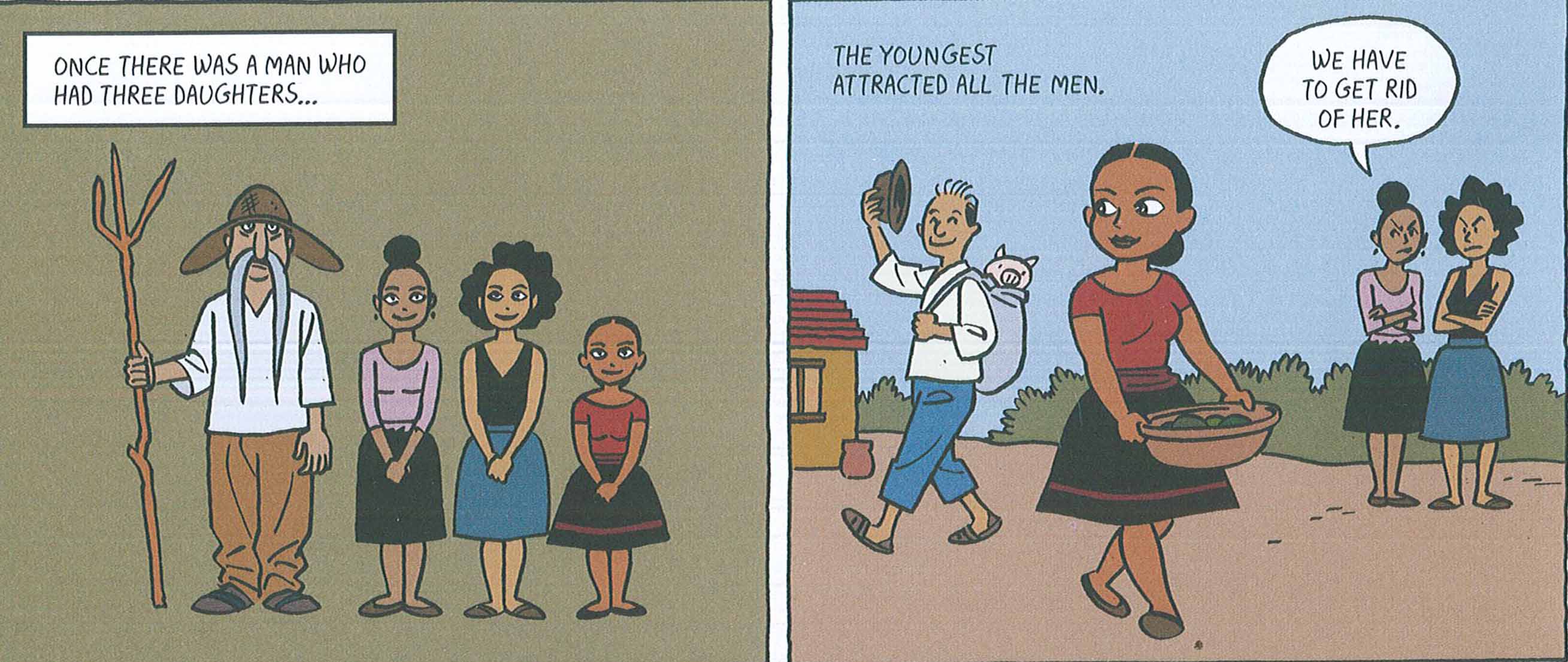

The same is true of the title character in “The Dragon Slayer,” Jaime’s first foray into children’s lit. Her story begins when she’s kicked out of her family by her sisters.

Much like the women from “Love and Rockets,” this dragon slayer doesn’t waste time wallowing in her misery, and soon lives up to the only name readers know her by:

Jaime’s brother and “Love and Rockets” co-conspirator Gilbert made his first kids’ comic, “Marble Season,” back in 2013. Jaime took a bit longer, but much like Gilbert’s children’s book, the three stories in Jaime’s “The Dragon Slayer” are sandwiched between brief essays that locate the tales within their cultural and geographical context.

“The Dragon Slayer,” for example, as Latinx children’s author F. Isabel Campoy notes in her opening essay, mashes up medieval stories of knights and dragons, brought to Latin America from Spain, with stories of tough Latin American women. Many earlier versions of “The Dragon Slayer” contain religious references as well, an old woman who helps her early in her journey representing the Virgin Mary, and the dragon’s seven heads representing the seven deadly sins. As Campoy explains, Spain already held a “crossroads” of Catholic, Jewish, Arab, and “Moorish” within its cultural history, which, when imported to Latin America, got mixed up with an even wider range of stories from Maya, Aztec, Inca, and other indigenous cultures.

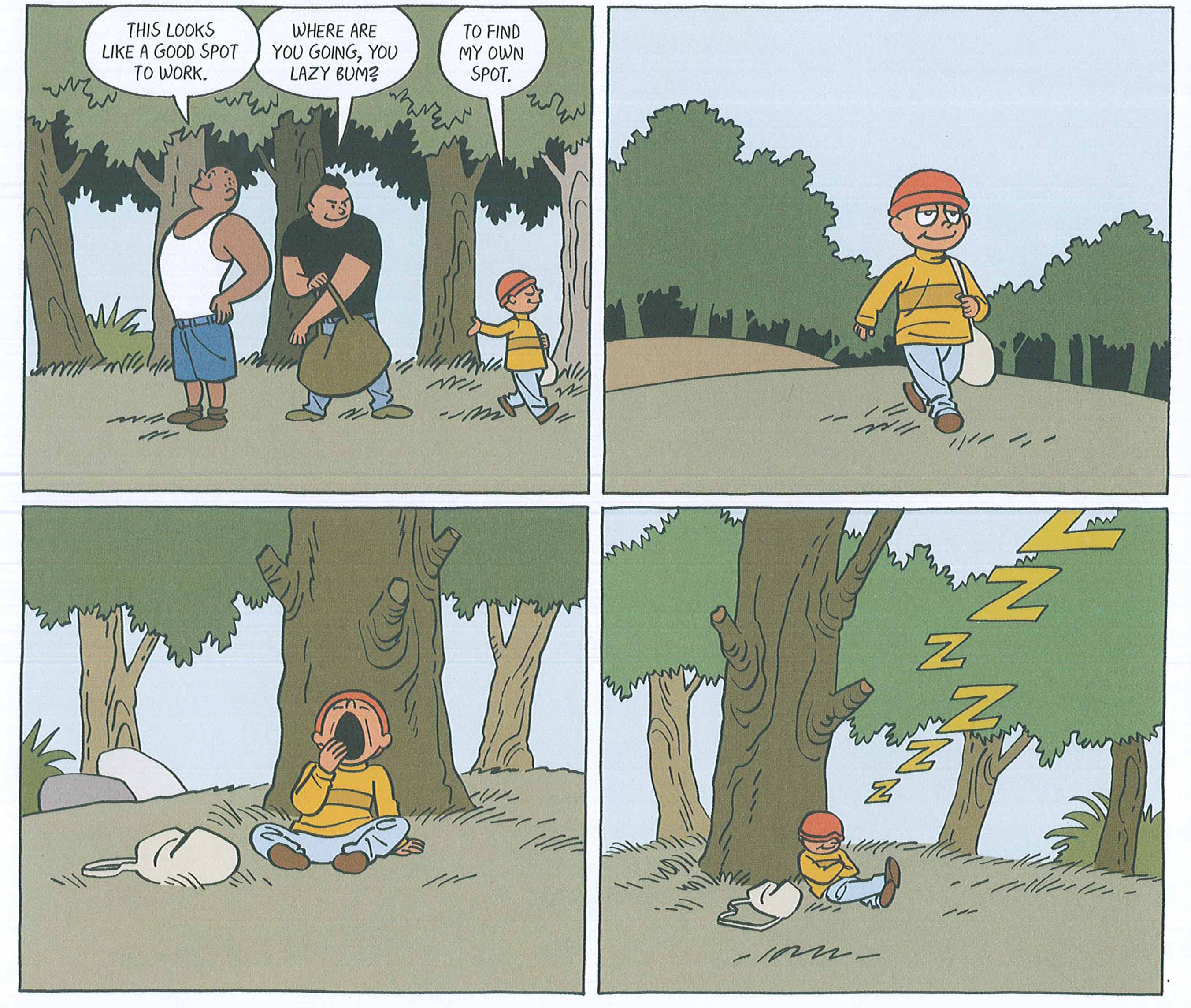

All of these stories are recognizable on some level, however, to anyone who grew up with any bedtime stories at all. The closing piece, “Tup and the Ants,” smacks of Tom Sawyer,

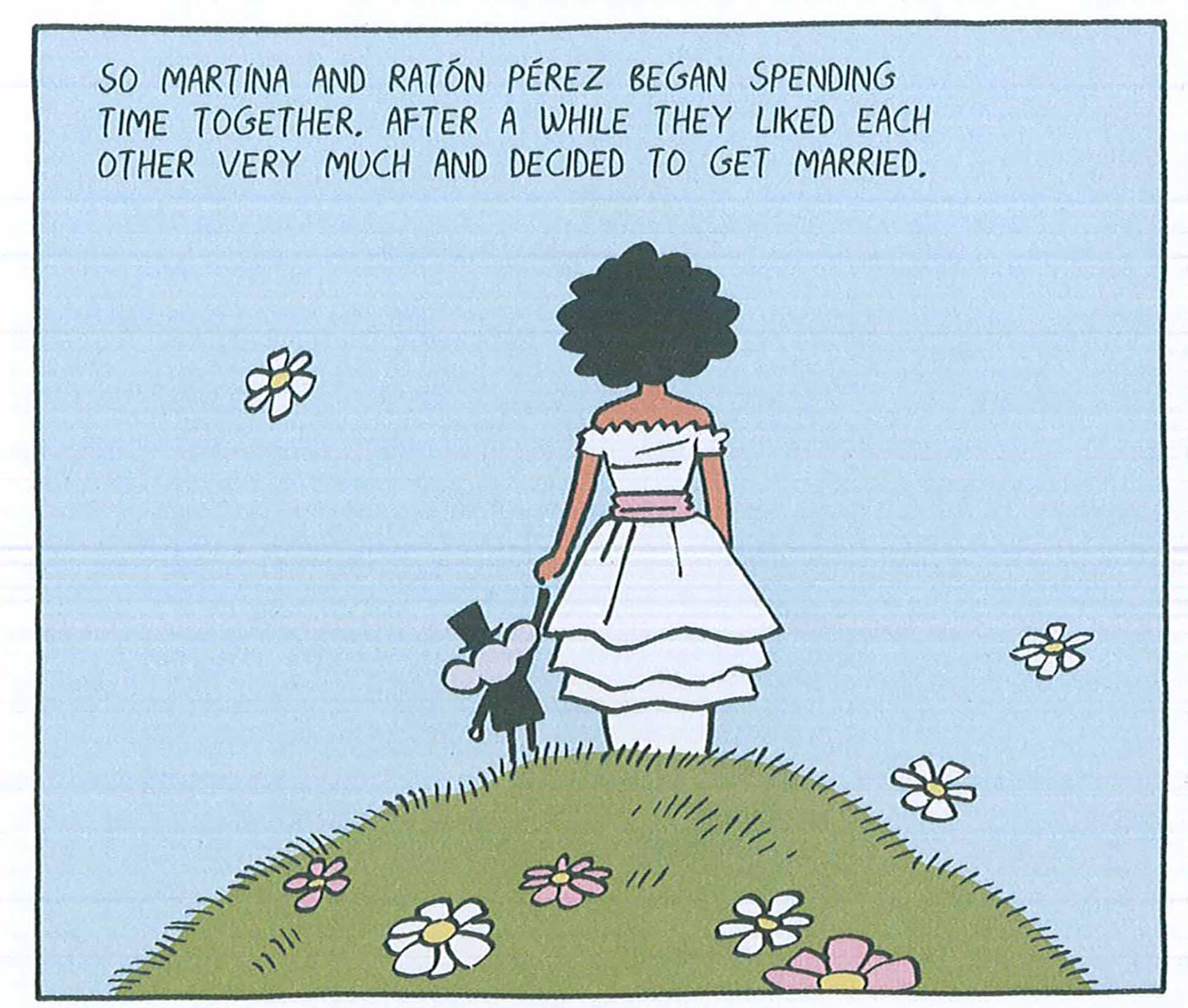

as the lazy Tup enlists feisty ants to do his work for him. The middle story, “Martina Martinez and Perez the Mouse,” echoes “Froggie Went a Courtin’.” The title character rejects feline, canine, and feathered suitors

in favor of a mouse:

Hernandez sticks to simple storytelling for young readers, at a steady pace of six panels per page. As you can see from the full page above, he expertly mixes color and perspective, in each frame showing characters from different angles and perspectives. The bold bright tones, framed on the title pages by black and white Aztec-like designs, are especially fun for his longtime fans, notes Rob Clough of “The Comics Journal,” because aside from his covers, we don’t usually get to see his drawings in full-color glory.

“I have kid [characters] in my adult comics,” Hernandez confessed to Calvin Reid of “Publisher’s Weekly,” “but they play by my rules. Now that I’m writing for children, I’m playing by their rules.” Hernandez notes that he didn’t grow up with these stories himself, but “they had that ring of truth” and “sheer wackiness” that he “connected to [his] own childhood.”

Since this was Hernandez’s first shot at children’s lit, he wasn’t sure whether or not he’d succeeded. As he told Alex Dueben of “Smashpages,” “I was really nervous when I finished it. I was happy with what I did, but I was like, ‘Kids are going to think I’m a dork.’ Why didn’t I make things blow up more? But it seems to be getting good response, and I’m happy about that.”

Campoy claims in her introduction that folktales “teach us how to be better human beings.” I’m not sure how universally true that is—especially since Tup’s tale seems to extol the virtues of laziness—but these stories do convey positive messages about strength, common sense, and kindness. Despite its notable lack of explosions, “The Dragon Slayer” will entice kids and parents alike to join the parade on its cover.