Originally posted November 2014. Thanks to Better World Books, 215 S. Main St. in Goshen, for providing me with books to review. You can find all of these books at the store.

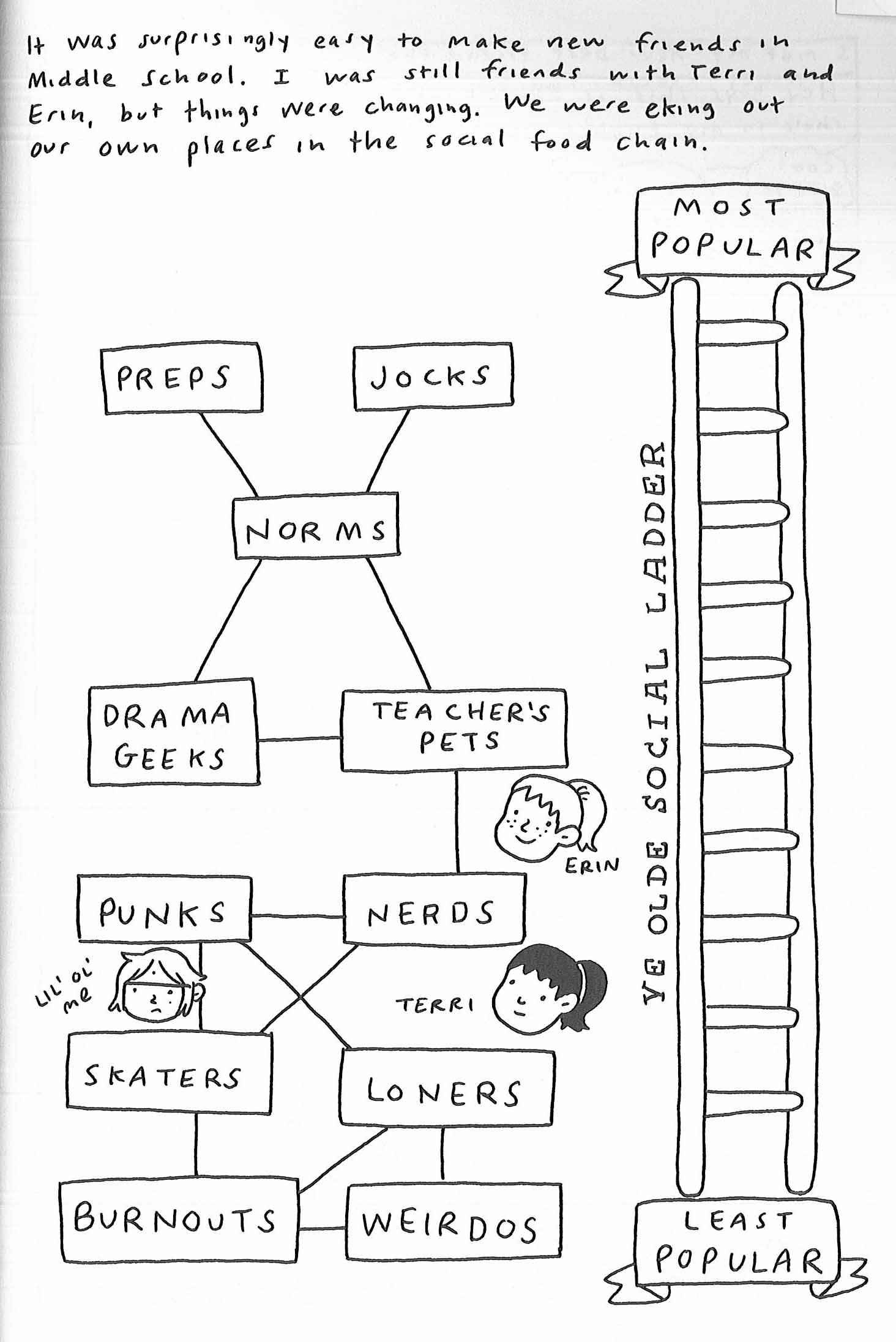

Did anyone actually enjoy middle school? According to my own (extremely) random polling, most people remember middle school not fondly, but as an early exercise in institutionalized torture. Part of the problem was its often baseless, incomprehensible, yet rigid hierarchies, codified here by Liz Prince in her graphic memoir “Tomboy”:

As the illustrated narrator version of Prince soon discovers, however, hierarchies never work as simply as a diagram would suggest. There are multiple subgroups to identify with and be ostracized from. Perhaps the worst social division to find yourself on the wrong side of—especially in the volatile soup of middle school—is gender.

The book begins earlier, however, with Prince’s four-year-old self screaming so loudly she can be heard down the street. The source of the tantrum is a gift from her grandmother: a dress, which she refuses to even try on. Fortunately for Prince, her parents listen and back her up, letting the relatives know that they should do their future clothes shopping for Prince in the boys’ rather than the girls’ section. Prince’s battle with her relatives was only the first of many such confrontations, not all of which were not so easily won.

Prince explains how she never experienced any confusion about her identity, never wanted to be a boy rather than a girl. She spends a good chunk of the story, in fact, pining for a boyfriend. She just very clearly and firmly doesn’t like the clothes and toys and other accoutrements meant to accompany girlhood in the U.S. Also (supposedly) more like a boy than a girl, she loves comics.

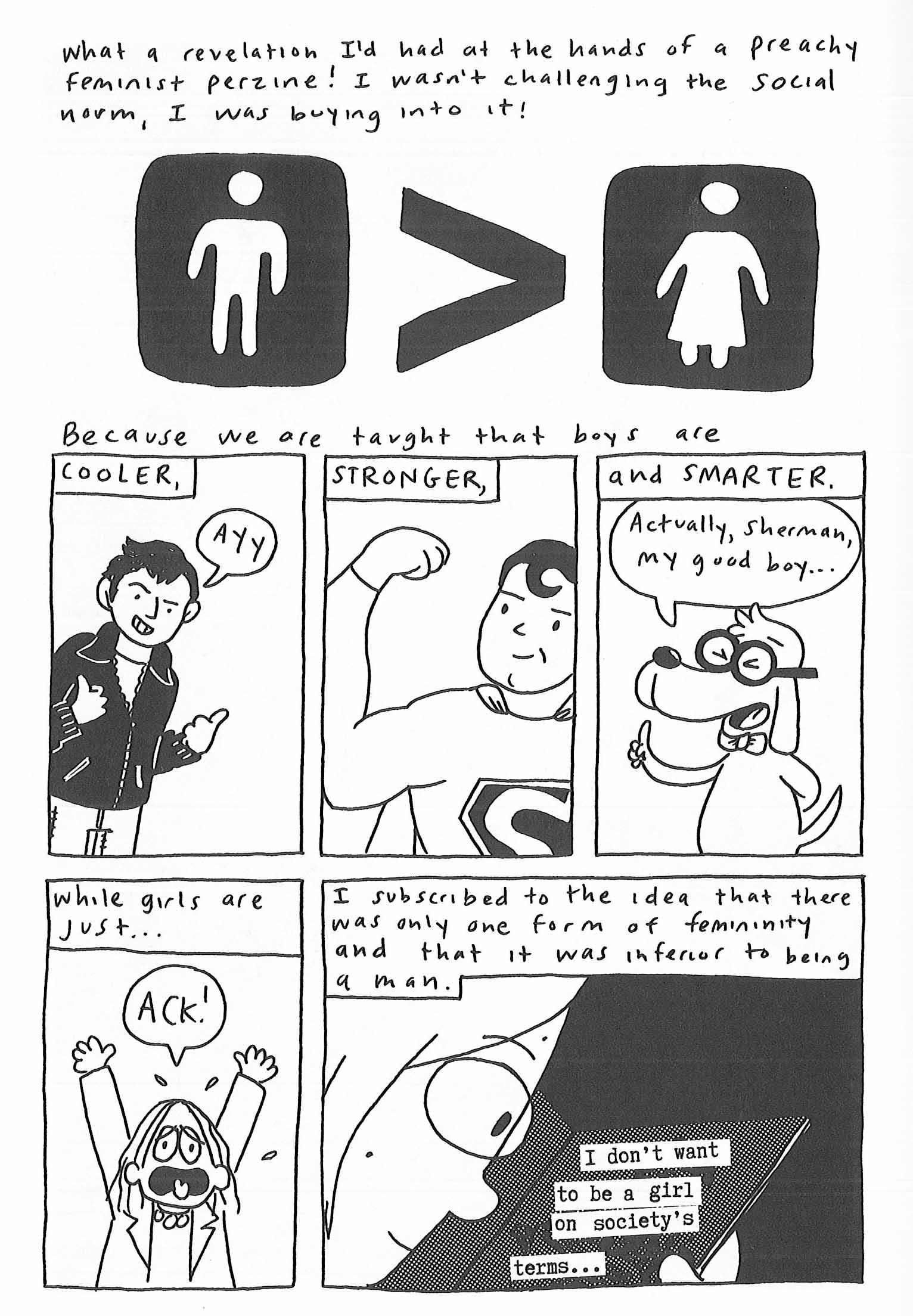

Not only does Prince make an outstanding case that comics are much better suited for kids, teens, and adults than for babies, she also demonstrates how comics are an ideal medium for telling her particular story. Both comics and gender representation, after all, thrive on the power of icons:

![]()

Prince’s simple but evocative line drawings are harder to pull off than you might think: less expert artists than Prince have tried this style and run into common problems like flat settings, character confusion, and narrative confusion, which in the world of comics often means that readers don’t know which frame comes next. Comic strip artists like Charles Schulz were masters of this style. Schulz constructed his strips so seamlessly that readers didn’t have to think about who was whom while they read. No one ever confused Charlie Brown’s little sister Sally with Frieda the red-haired girl, or Linus with Pig Pen. Schulz would throw readers an iconic element as a quick signal—Frieda’s pile of hair or Pig Pen’s dust cloud—so that they could stay focused on the action, and most importantly, the joke.

Readers can easily and instantly identify Liz Prince the narrator by two pointy cowlicks that look like horns. Most importantly, they also contribute to more subtle messages, like the connection between Prince and her mom, who sports the same hairdo.

Prince owes a lot to Charles Schulz, as well as more recent comics artists, such as Jeffrey Brown, best known for “Darth Vader and Son” and its subsequent spinoffs. Whereas Schulz’s and Brown’s storylines are fueled by their characters’ iconic simplicity, however, Prince challenges the stereotypes within her own story, as well as within our culture at large. Step by step, Prince as narrator puzzles through the gender messages she both gives and receives, until she has a revelatory encounter as a teen with the work of another subversive comics artist, Ariel Schrag. (Not coincidentally, Schrag is also the editor of “Stuck in the Middle,” a 2007 anthology of comics about middle school.)

Unless you’re very young or not terribly reflective, you’re not likely to learn anything new about gender roles in “Tomboy”—but that’s not the point of reading this book. Prince’s wit is both engaging and contagious. If you know of any middle or high school students trying to figure themselves out, definitely pass this book on to them. Do make sure, however, that their parents are okay with a bit of edgy language, because the F word is a frequent tool for self-defense as Prince and her friends navigate the brutal worlds of both middle and high school.

For the rest of us, grateful to have moved beyond middle school into a somewhat saner world, not only is “Tomboy” a good read, it’s also an excellent reminder of what it feels like to be an outsider. Its all-too-poignant details about life in middle and high school create, in their cringe-worthy glory, a memoir of mean—but also a reminder of why feeling like an outsider every once in a while can serve as a good check-in with our identities, and our capacity for compassion.