In celebration of Black History Month, here’s a review originally published for the “Elkhart Truth” in May 2015. Other Rosarium titles I’ve reviewed are Whit Taylor’s “Ghost” (February 2018) and a double review of “Kid Code” and “Malice in Ovenland” (February 2015).

Rosarium Publishing allows me free access to their comics titles. Thanks to Better World Books, 215 S. Main St. in Goshen, for providing me with books to review. You can find or order all of the books I review at the store.

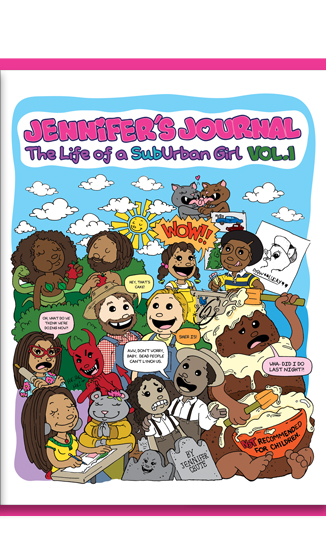

Artist Jennifer Cruté worked for years as a commercial illustrator, but always drew her own comics and sketches on the subway as she traveled to and from her job. Her comics were simple, short sequences depicting funny and often uncomfortable moments from her life as a woman, an artist, and particularly a Black female artist. Her friends loved them, but she just saw them as doodles, until, as she told “Bitch Magazine,” in 2012, “I had a dream where Shirley Chisholm grabbed me and shook me while screaming, ‘It’s not just a stupid comic! Finish it!’ Pretty scary. So, I got on it.”

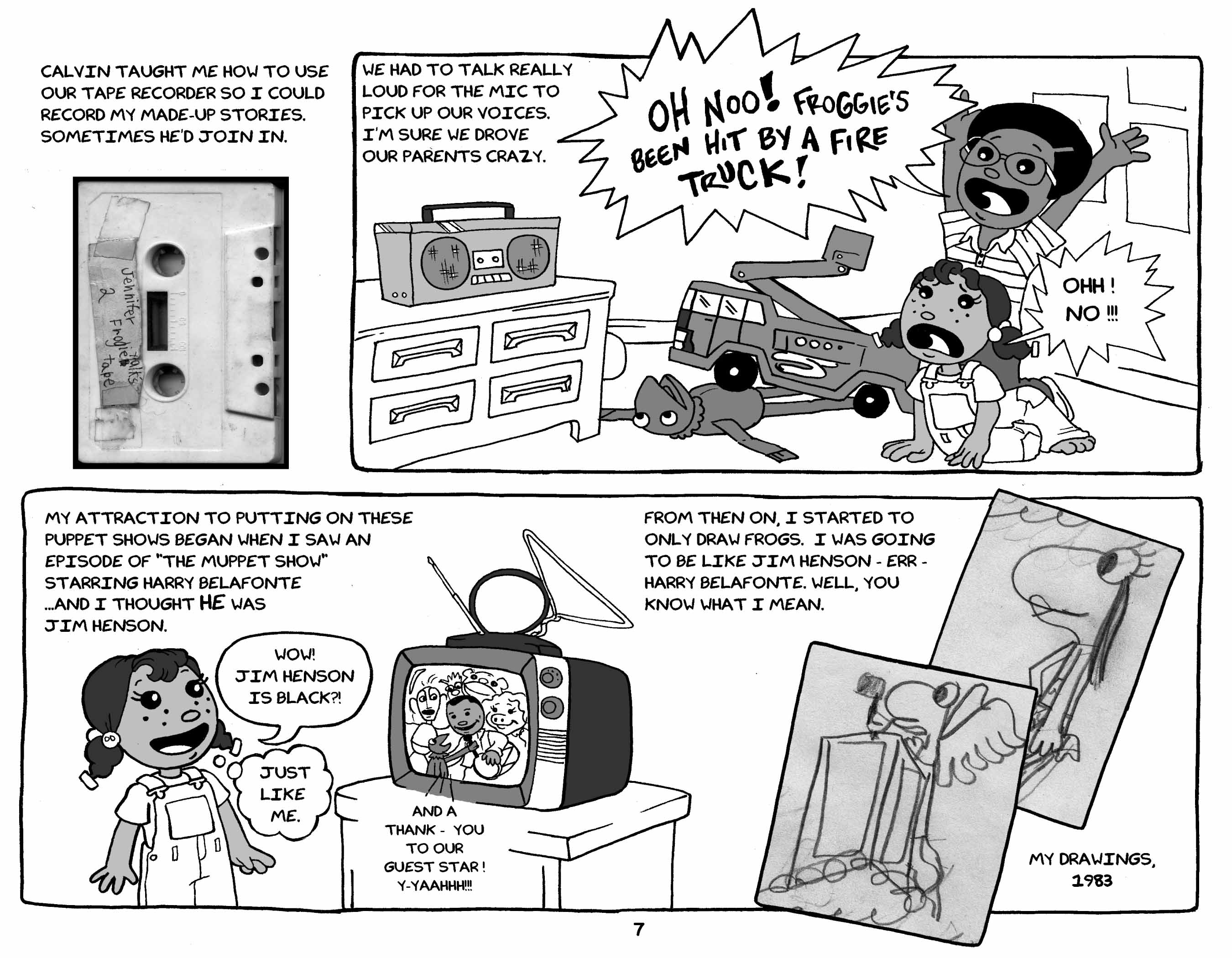

Cruté’s subconscious Chisholm was right: “Jennifer’s Journal” is definitely more than a “stupid comic.” The stories are fragmented, a collection of experiences rather than a polished narrative, but that slice-of-life quality only adds to the book’s charm and impact. This page, for example, where she’s discussing the influence of her older brother on her life as an artist, draws readers in with a story that most can relate to: siblings entertaining themselves in creative and sometimes ridiculous ways.

It also serves to educate readers who didn’t have to struggle as kids to find positive media role models. As Cruté explained in a recent podcast interview, whenever she tried to talk to her white friends and acquaintances about the challenges of growing up Black, “if I got angry or showed any emotion, people wouldn’t listen.” She began to ask herself, “how can I make [people] look and listen?” She found that her comics served the dual purposes of education and affirmation, depending on whom she showed them to. For her white friends, she noticed laughter, “an uncomfortable laugh [that] . . . means that some gears might be turning in your head now.” Friends of hers who had experienced racism would respond entirely differently, more like, “Oh my god, I’ve been trying to explain this my whole life!”

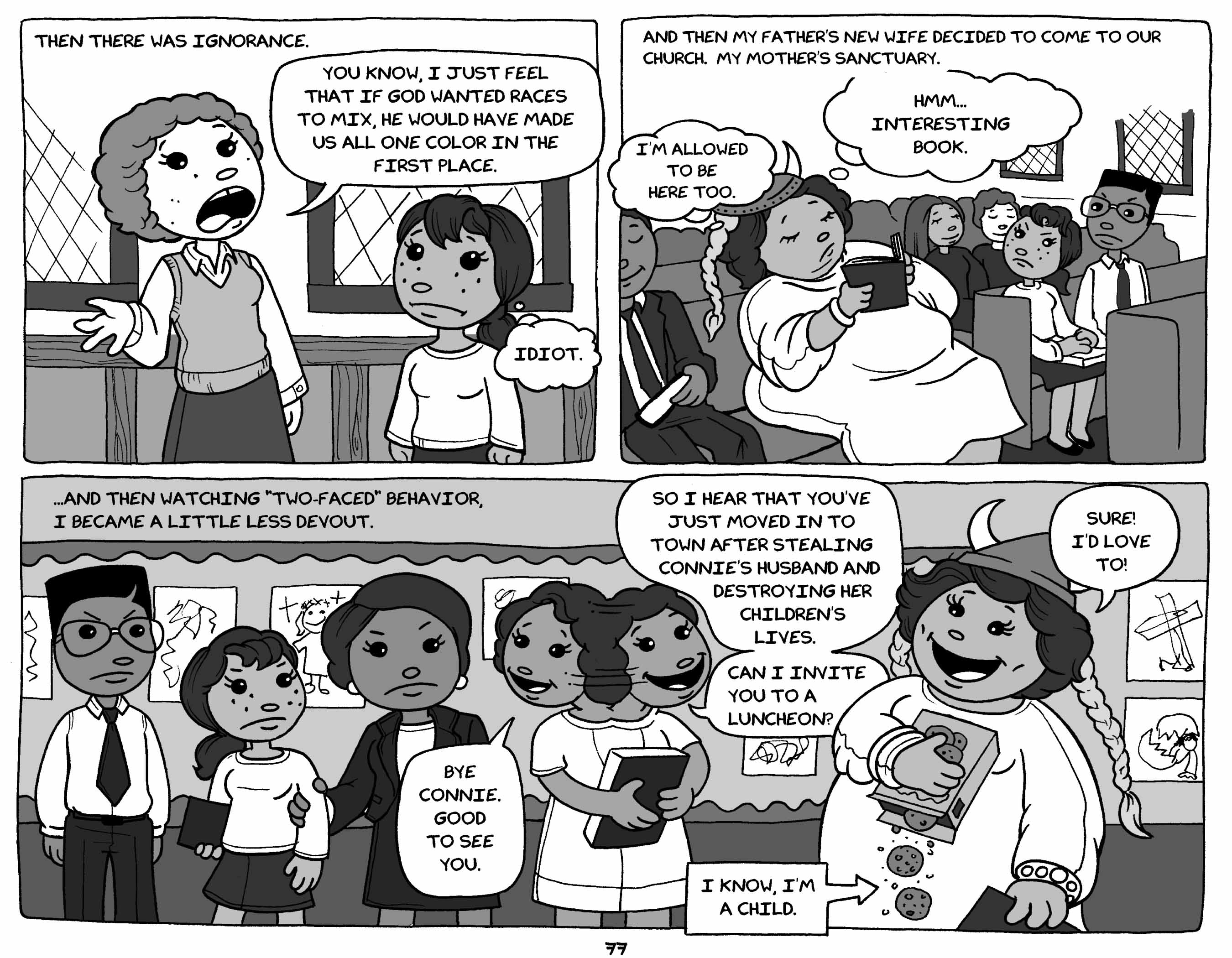

The back-cover blurb downplays the book’s more intense scenes. “I draw simple characters with round figures to soften the complex and contradictory life situations I depict,” writes Cruté. She might “soften” some of these situations, but that doesn’t mean she avoids them—and for good reason, a handful of pages aren’t “soft” at all. One frame illustrates a trip to the grocery store when Cruté and her father were greeted with the “N word” by a perky toddler in a grocery cart. His mother wheels him away whispering “Honey, that’s an inside word,” while another shopper looks on in shock. In a later section of the book that narrates Cruté’s spiritual journey, she illustrates some of her worst experiences at her mother’s church.

The racism in the top left frame, especially, is far from “simple,” but putting it out here in these “simple,” “round” characters can help readers think more carefully about how it works and why it’s so pernicious.

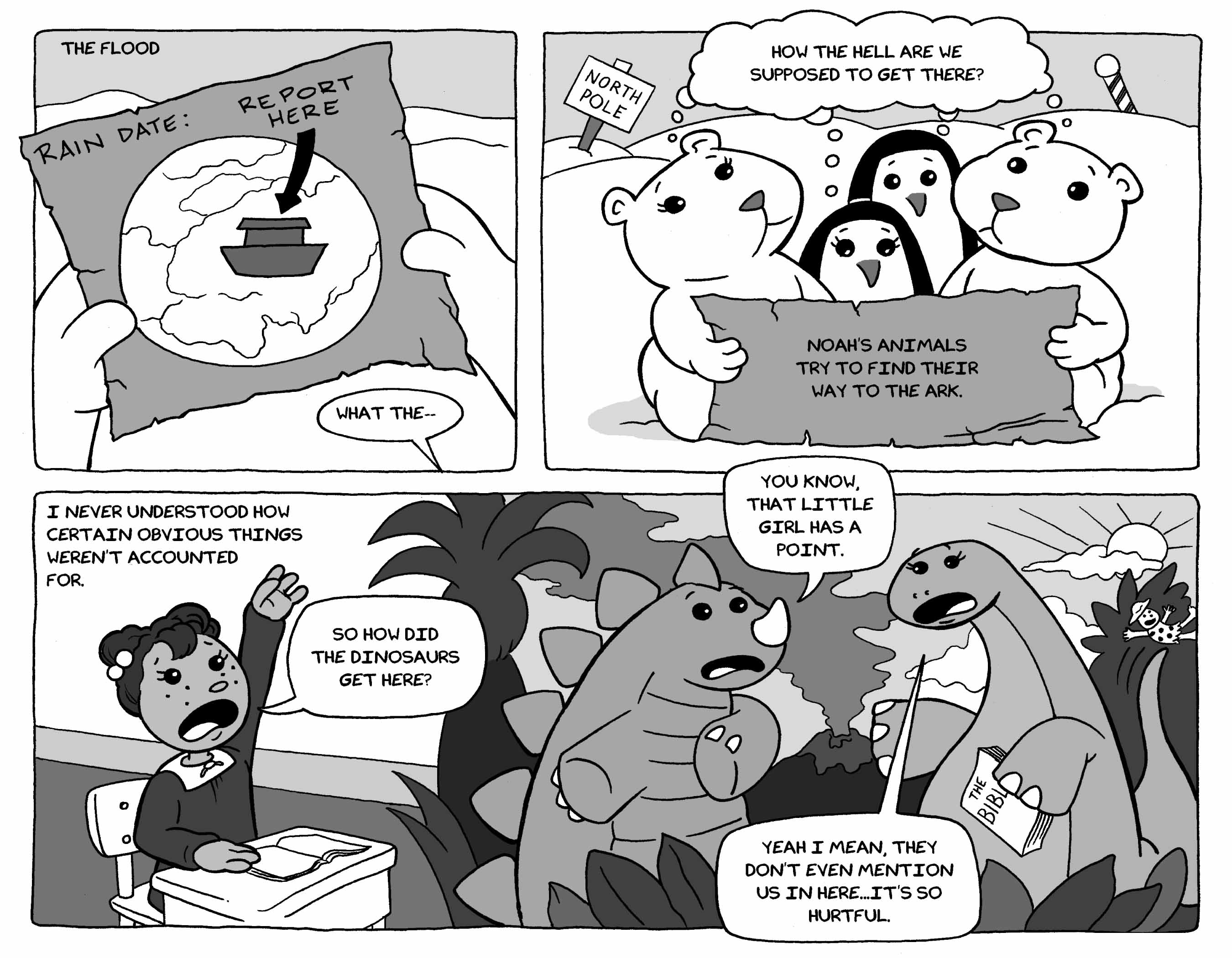

Much of the success of “Jennifer’s Journal” is in its power to ring true with practically anyone who’s been a kid in the US, whether black or white, urban or suburban. Even those who didn’t go to Sunday School can relate to the following frame just having been a kid in a classroom getting vague or unsatisfactory answers to really good questions:

Visual simplicity is hard to pull off well. Just because a drawing looks simple doesn’t mean it was easy to create. This is why advertising agencies are paid so much to develop “simple” logos. Comics have rarely proved as lucrative—for individual artists, at least—but I sure wish this one could be, especially having learned how challenging it was for Cruté to navigate the world of commercial illustration. She shares one of her most disheartening stories, about developing an ad for a haircare product, in her podcast interview. “They kept asking me to change the features of the woman,” she explained, but she couldn’t get her face quite “right,” and couldn’t figure out what she was doing wrong until her boss finally said, “just make her look more European.” Cruté became a lot pickier about her commercial work after that experience. As awful as it was, it helped her realize, “I don’t want to use this talent that I have and pour it back into a system that made me feel so inadequate in the first place.”

Fortunately for comics fans, the “Volume 1” in the title of this book implies that Cruté plans to channel her talent into a Volume 2. Also keep an eye out for a graphic novel Cruté is developing about her uncle, hip hop legend DJ Red Alert, who is credited with helping artists like Queen Latifah and Tribe Called Quest rise to fame.

Now that Cruté’s comics career has some momentum, she shouldn’t need Shirley Chisholm’s help to finish Volume Two, but let’s hope the congresswoman is still lurking in Cruté’s subconscious, just in case she could use another nudge.