Re-posted from February 2018, in honor of MLK Jr. Day tomorrow. See links below for reviews of Book One and Book Two. If you haven’t read any of these yet, look for the Top Shelf boxed set of the whole trilogy.

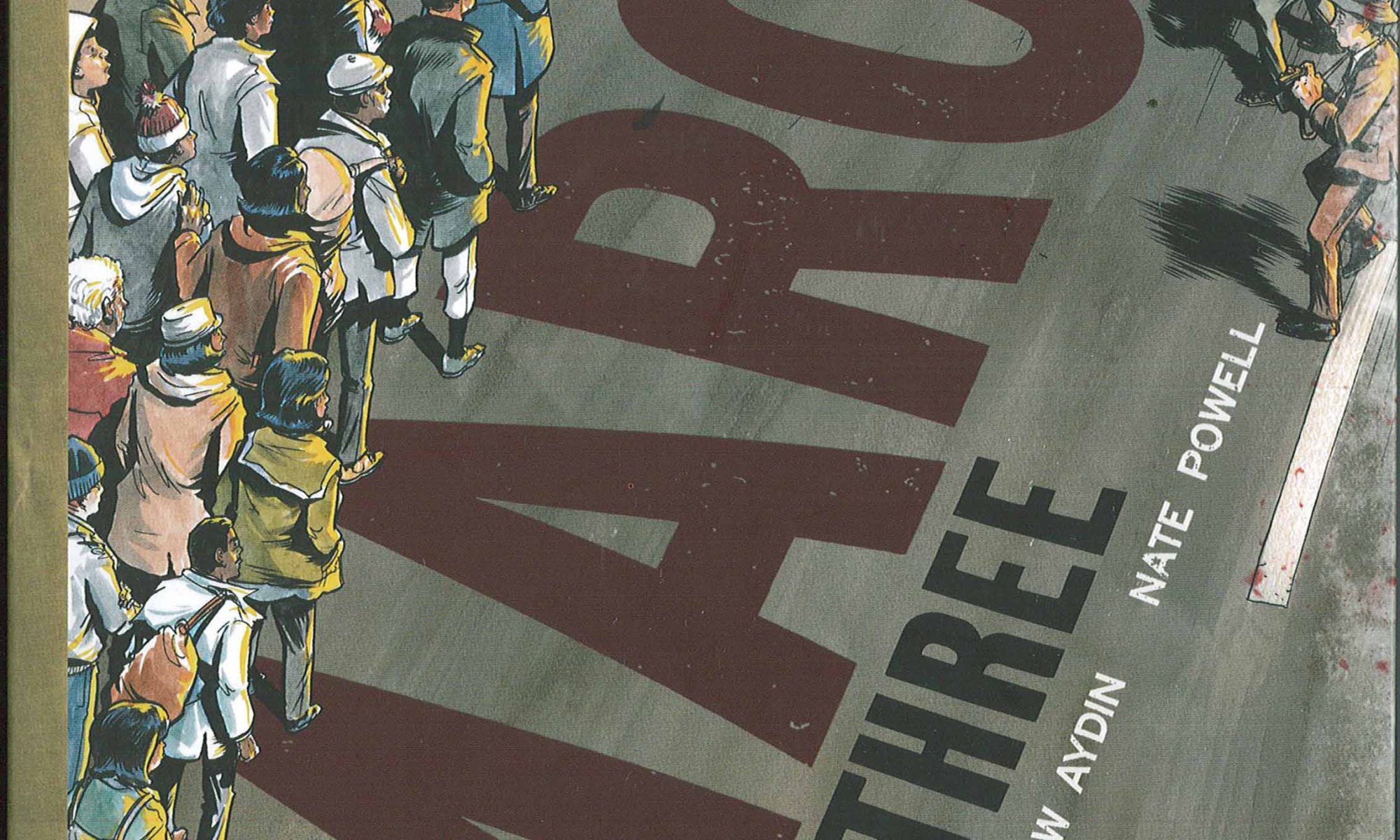

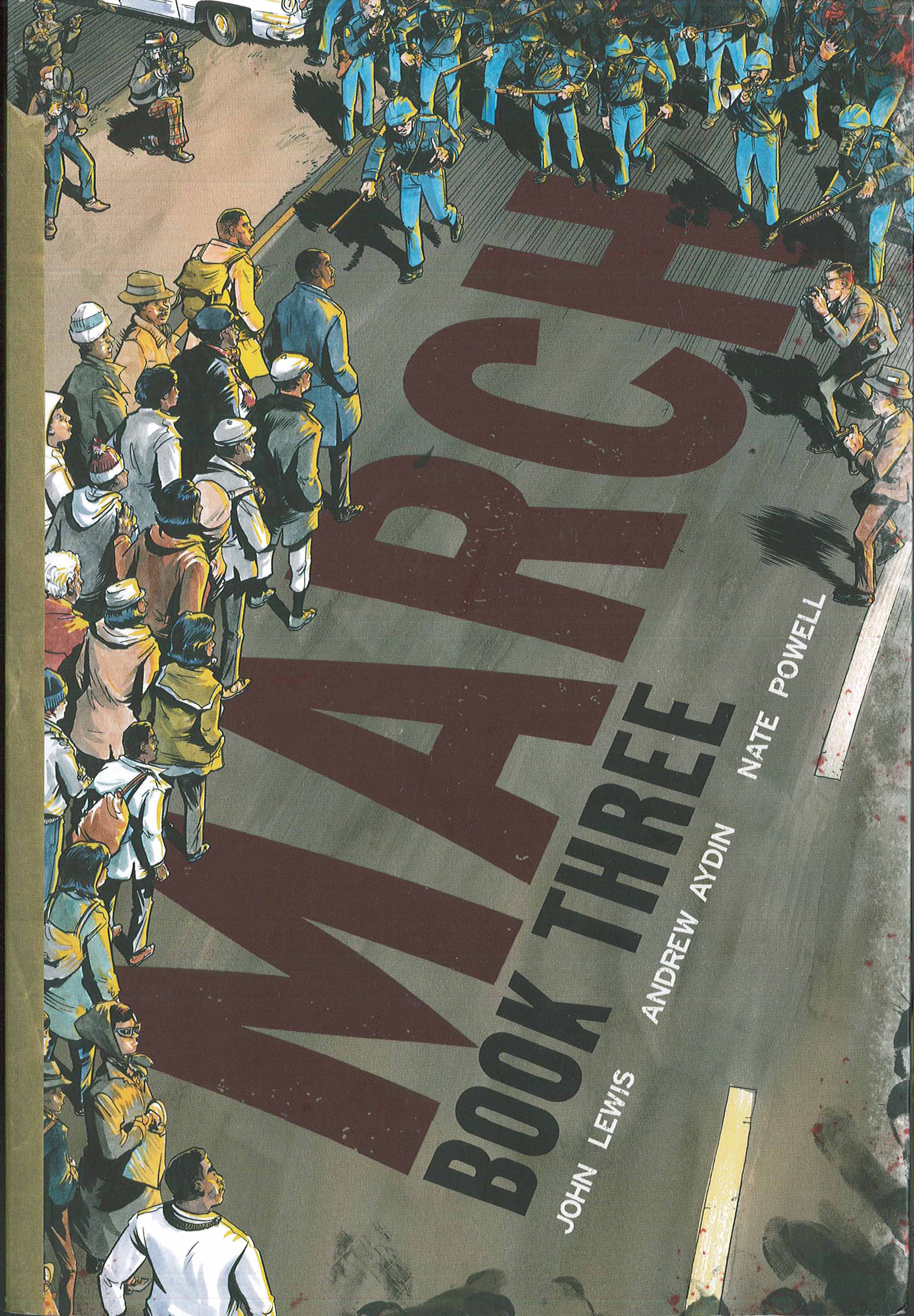

“March: Book Three,” by John Lewis, Andrew Aydin, and Nate Powell. 192 pages, Top Shelf Productions, Aug. 2016. Paperback, $19.99, 8th grade and up.

Thanks to Better World Books, 215 S. Main St. in Goshen, for providing me with books to review. You can find all of these books at the store.

U.S. Representative John Lewis, who narrates the conclusion of his civil rights journey in “March: Book Three,” has been arrested at least 45 times, most recently in a 2013 rally for immigration rights. As one of the founders of the Civil Rights Movement and the last surviving speaker of the 1963 March on Washington—which culminated in Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech—Lewis remains an advocate for getting in trouble. He calls this type of trouble “necessary trouble,” imperative when something in society is “not right, not fair, not just.”

In the sweep of the whole “March” trilogy, Lewis recounts how he went from being a kid in rural Alabama who preached to his chickens, to chairing the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), to receiving the Medal of Freedom from Barack Obama in 2011. I reviewed Book One when it came out in 2013 and Book Two in 2015. Book Three, which covers his civil rights work from the fall of 1963 to Selma in the spring of 1965, wraps up the trilogy with beautiful and devastating power and grace.

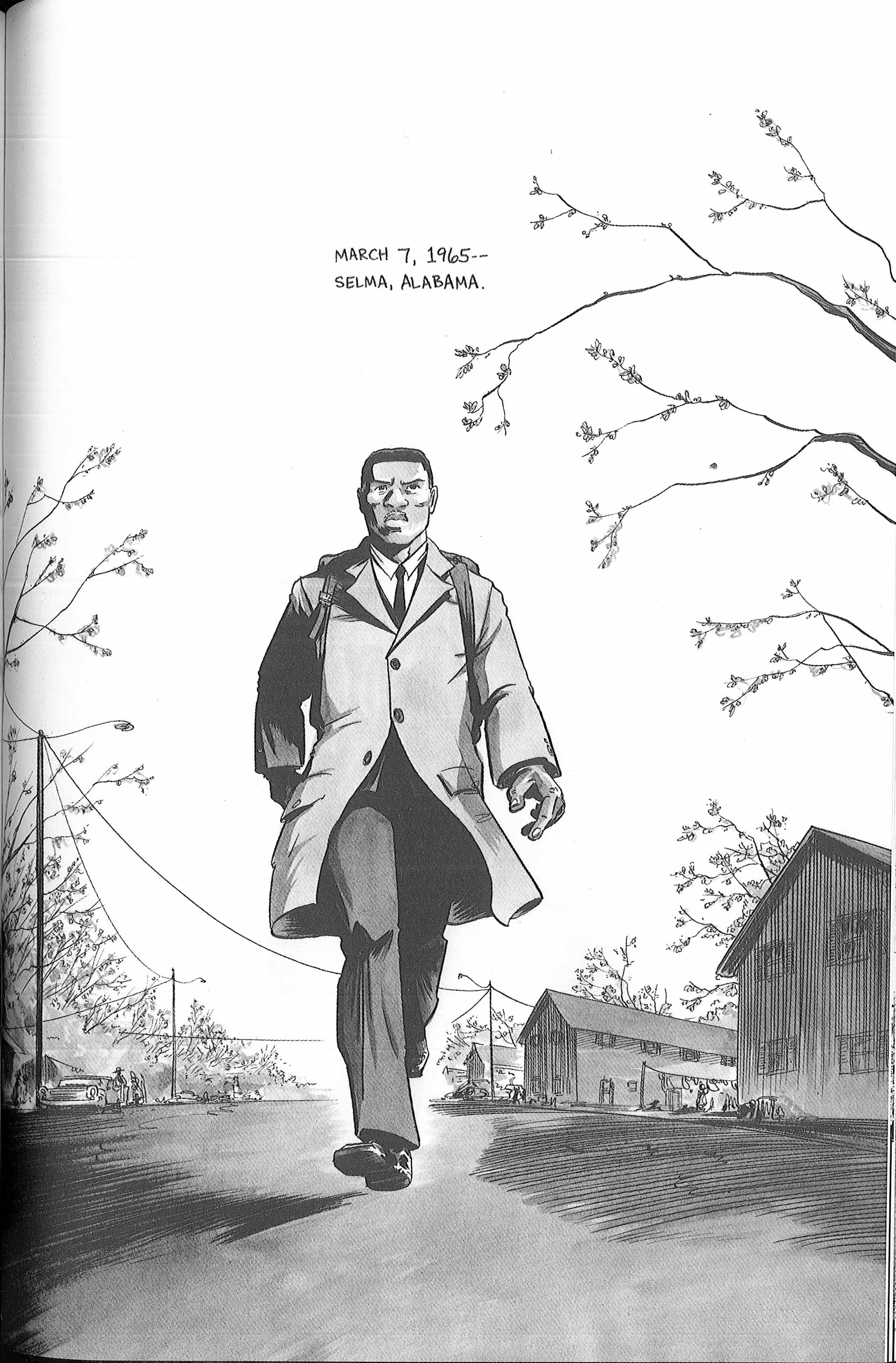

This book most certainly leaves its readers with hope, but a difficult, tentative hope, which reminds us that we need to take the long view and keep working. Lewis himself kept going, despite years of violence and political setbacks. Here illustrator Nate Powell depicts him propelled by purpose as he reaches Selma, ready to begin the famous protest march to Montgomery:

Book Three was released in August 2016, three months before the U.S. elected a president unashamed of either his own racist rhetoric, or that of his supporters. As if presaging our nation’s current grim chapter, this volume begins with the most horrifying moment of the Civil Rights struggle: September 15, 1963. The bombing of a Birmingham church—on Youth Day, no less—killed four girls and sent twenty-one more people, mostly kids, to the hospital. This is a famous chapter in Civil Rights history, but to see it playing out—to watch the mother running in panic to find her daughter Denise, met only by husband holding her daughter’s lone white shoe amidst the clearing smoke—well, I’m crying again as I write this, and again as I try to edit this description into something more poignant. Words fail here, but Powell’s illustrations won’t let you down.

As in his previous two volumes, Lewis also fills in some lesser-known figures of the Civil Rights movement, such as the two teenage boys, Johnny Robinson and Virgil Lamar Ware, who were shot in the aftermath of the bombing. For some individuals in our sick society, this bombing was empowering rather than sobering, and these two boys quite literally got caught in the crossfire of that raw hatred. Yet Lewis, so fervently committed to nonviolence, reminds readers to focus on the societal mechanisms that create and fuel hate, that pit citizens against each other, by citing Martin Luther King, Jr.’s funeral sermon three days later. King implored the stunned congregation to “be concerned not merely about who murdered [the four girls,] but about the system, the way of life, the philosophy which produced the murderers.”

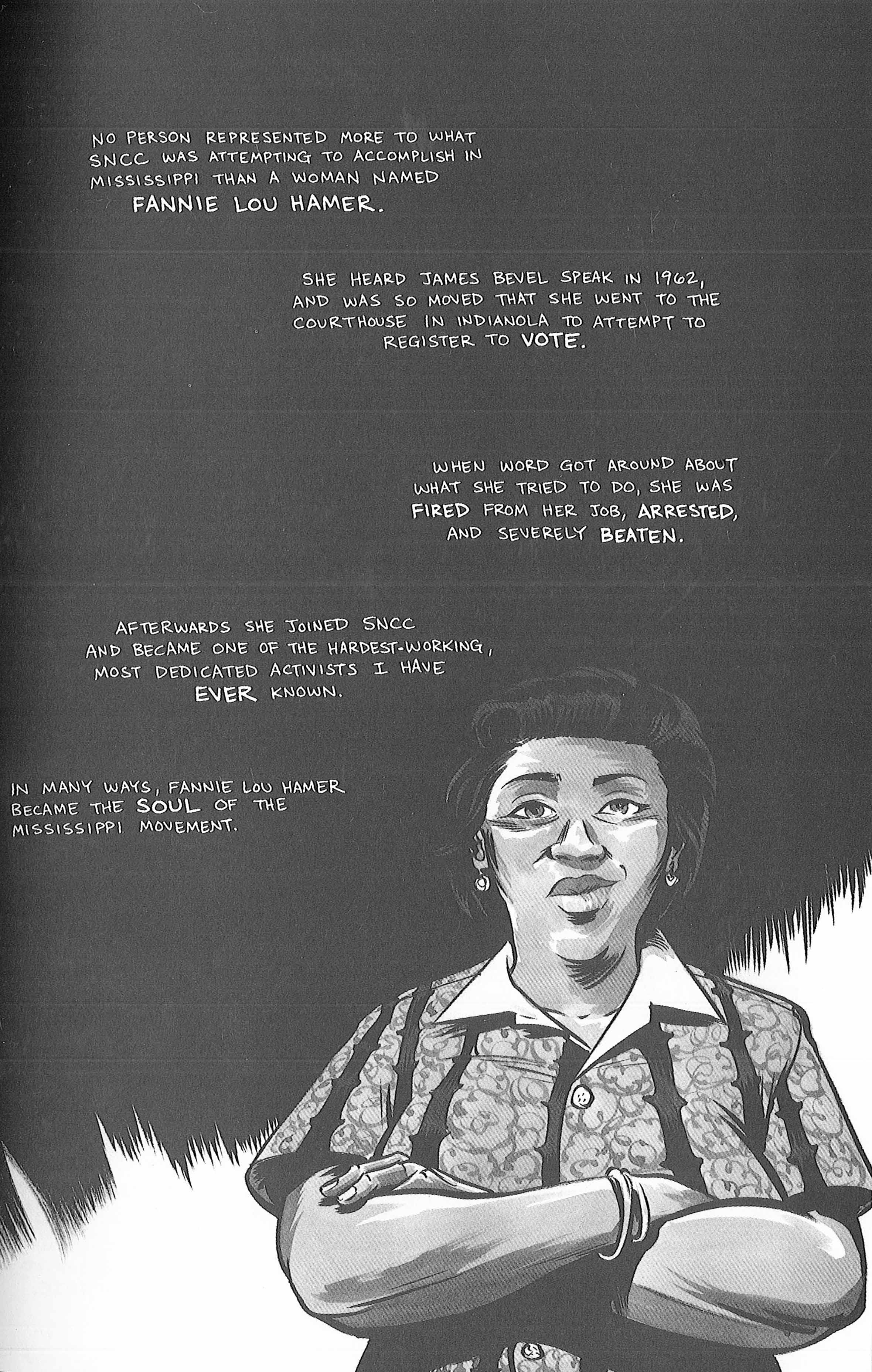

Other crucial but less-familiar leaders, like Bob Moses and Fannie Lou Hamer, are given full-page treatments:

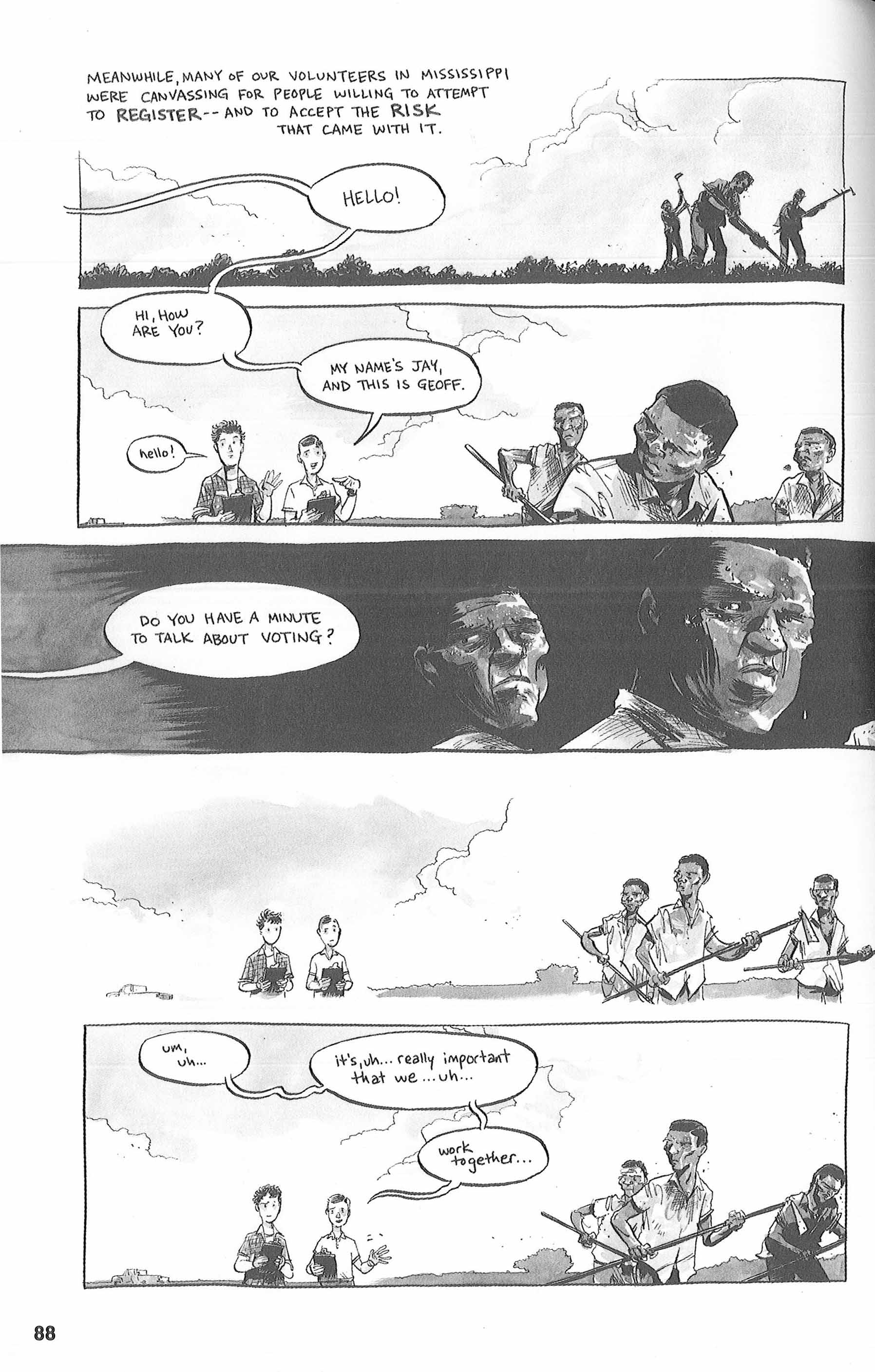

The stylistic juxtaposition of the two full-page panels I’ve shared so far demonstrate Powell’s deft use of contrast, making his gray-toned illustrations bloom, even without color. On the following page, Powell pulls the reader’s eye to the single long, black panel, fading the features of the timid canvassers to lines and dots on white:

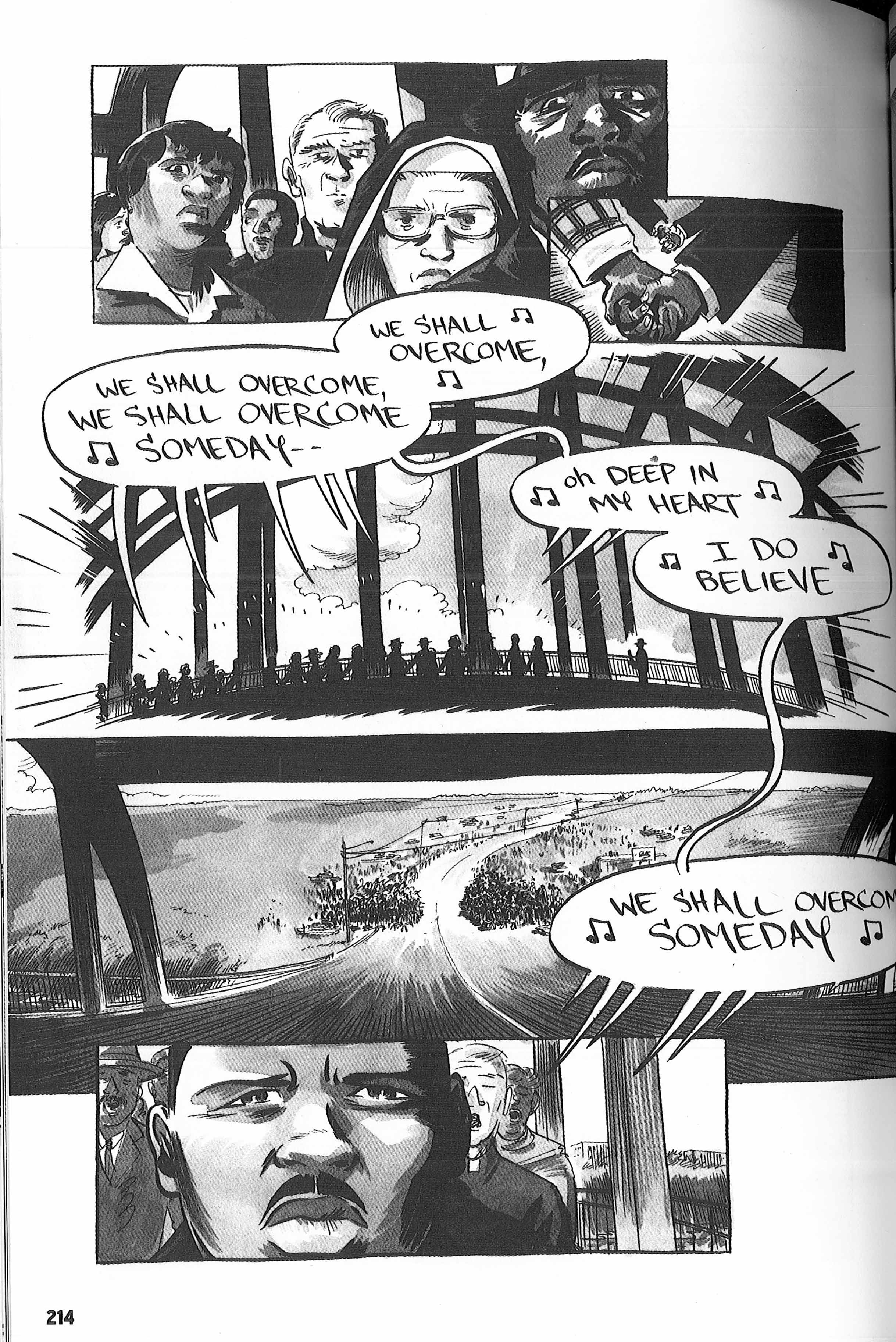

Yet later, as protesters make their second unsuccessful attempt to march across the Edmund Pettis Bridge from Selma to Montgomery—two days after their first attempt, Bloody Sunday, on March 7, 1965, which sends Lewis to the hospital after a severe beating and near-death experience—the words of their anthem tie the panels and the protesters together as the perspective zooms in and out:

The Edmund Pettis Bridge is where Book One began, and also where Book Three draws to a close. As challenging as conclusions can be, especially to a trilogy, Lewis and his co-author Andrew Aydin pull it off, looping readers who have been through the whole journey back around to the final, successful march from Selma to Montgomery.

“March: Book Three” adds a dose of reality to political rhetoric addled by the influence of “reality” TV. Originally released in the haze of the 2016 presidential race, it won the National Book Award for Young People’s Literature, the first National Book Award win for a graphic novel. “Who did you write this book for?” the National Book Foundation asks the book’s three creators on its site. “In such a toxic time,” Powell responds, “I hope this continues to be a part of the antidote for which we’re all hungry.”