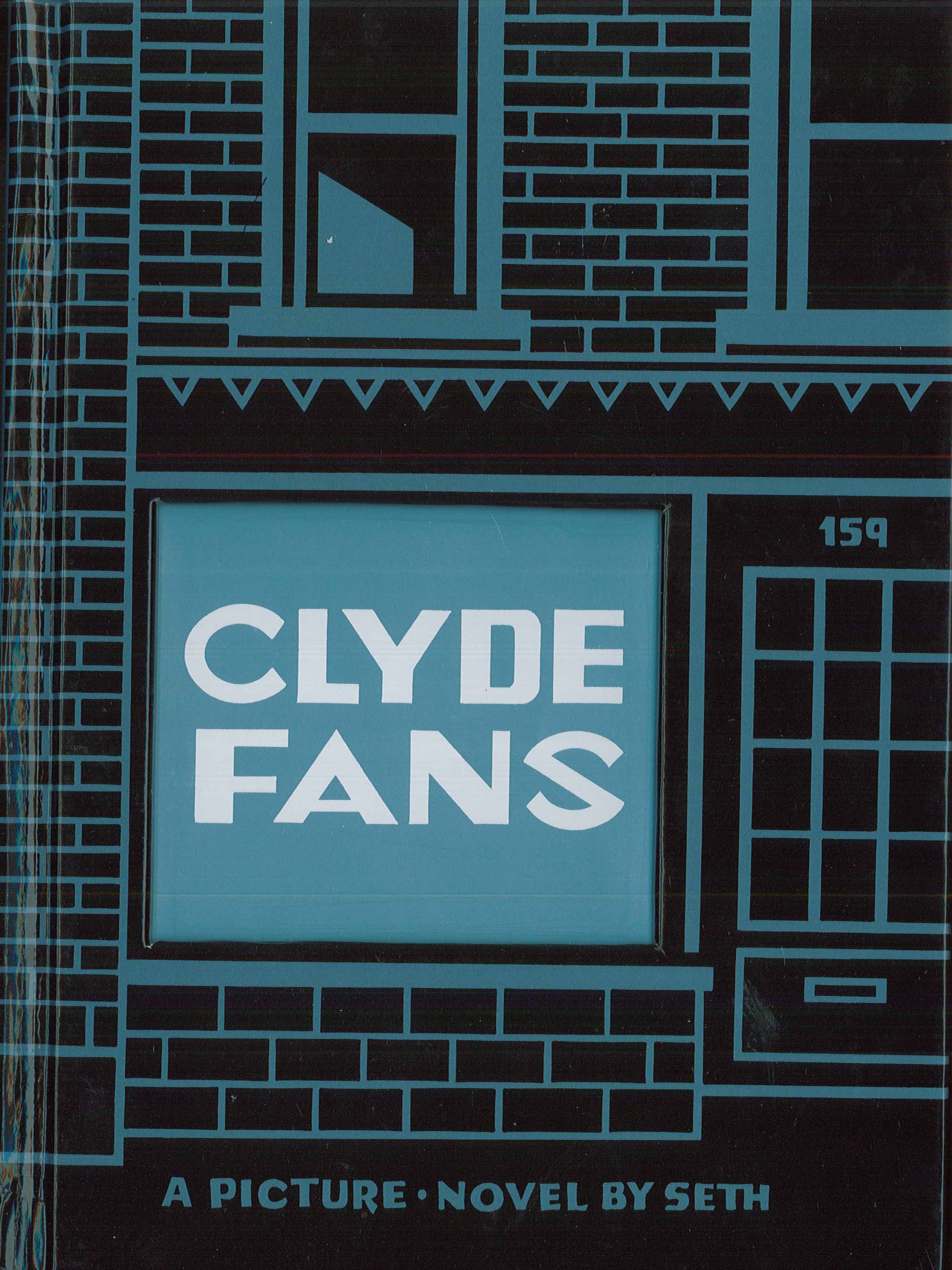

“Clyde Fans,” by Seth. Drawn and Quarterly, May 2019. 488 pp. Hardcover, $54.95. Adult.

Drawn and Quarterly sent me a free review copy of this book.

Canadian comics artist Seth cultivates an antique persona, complete with tie, overcoat, fedora, and what look like horn-rimmed glasses. With a given name like Gregory Gallant, you wouldn’t think he’d need a pseudonym.

But Seth likes to push boundaries: between people and their public and narrative personas, as well as between history and fiction. Seth’s first major book, “It’s a Good Life, If You Don’t Weaken,” published in 1996, was supposedly autobiographical, about his search for a “New Yorker” cartoonist who had disappeared from public view. As the book gained popularity, Seth eventually let on that he had manufactured the whole scenario, although much of the detail from the narrator’s life in the story was autobiographical. In an odd twist, despite the book’s fictional core, it’s often cited as the catalyst for an explosion of autobiographical comics that began in the 1990s and has fueled the genre since.

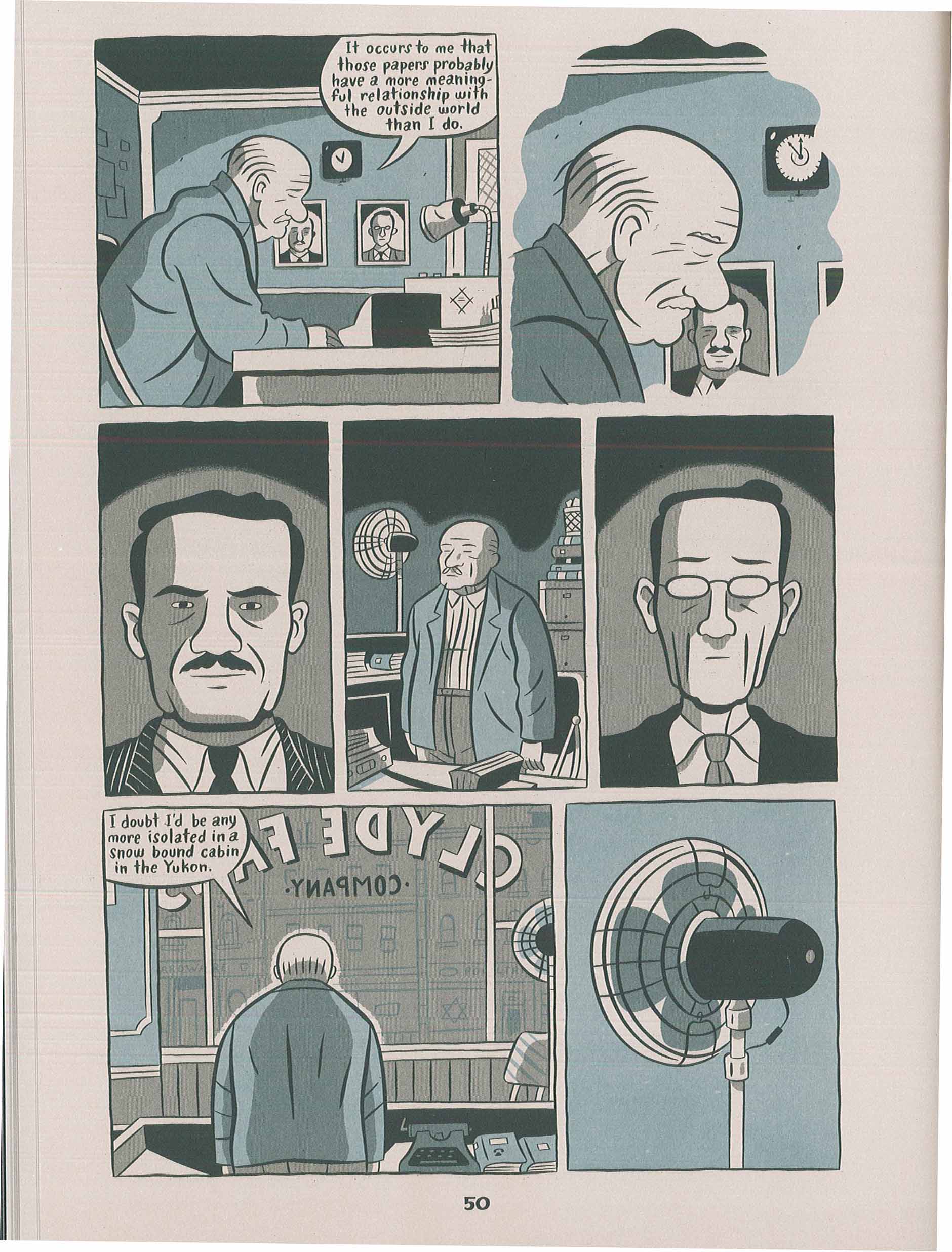

Seth’s just-released “Clyde Fans” is also fictional, although as he explains in an author’s note in the back of the book, it began with a real-life Ontario storefront of the same name, which he used to walk past. The office was closed, gathering dust, but he could see two framed portraits on a back wall, and wondered about the story behind those two men and their defunct business. He began writing a serial comic about Clyde Fans and the two brothers who ran it, whom he named Abe and Simon. Abe narrates in the image below, and you can see the two portraits hanging on the wall behind him before the frames zoom in for close ups:

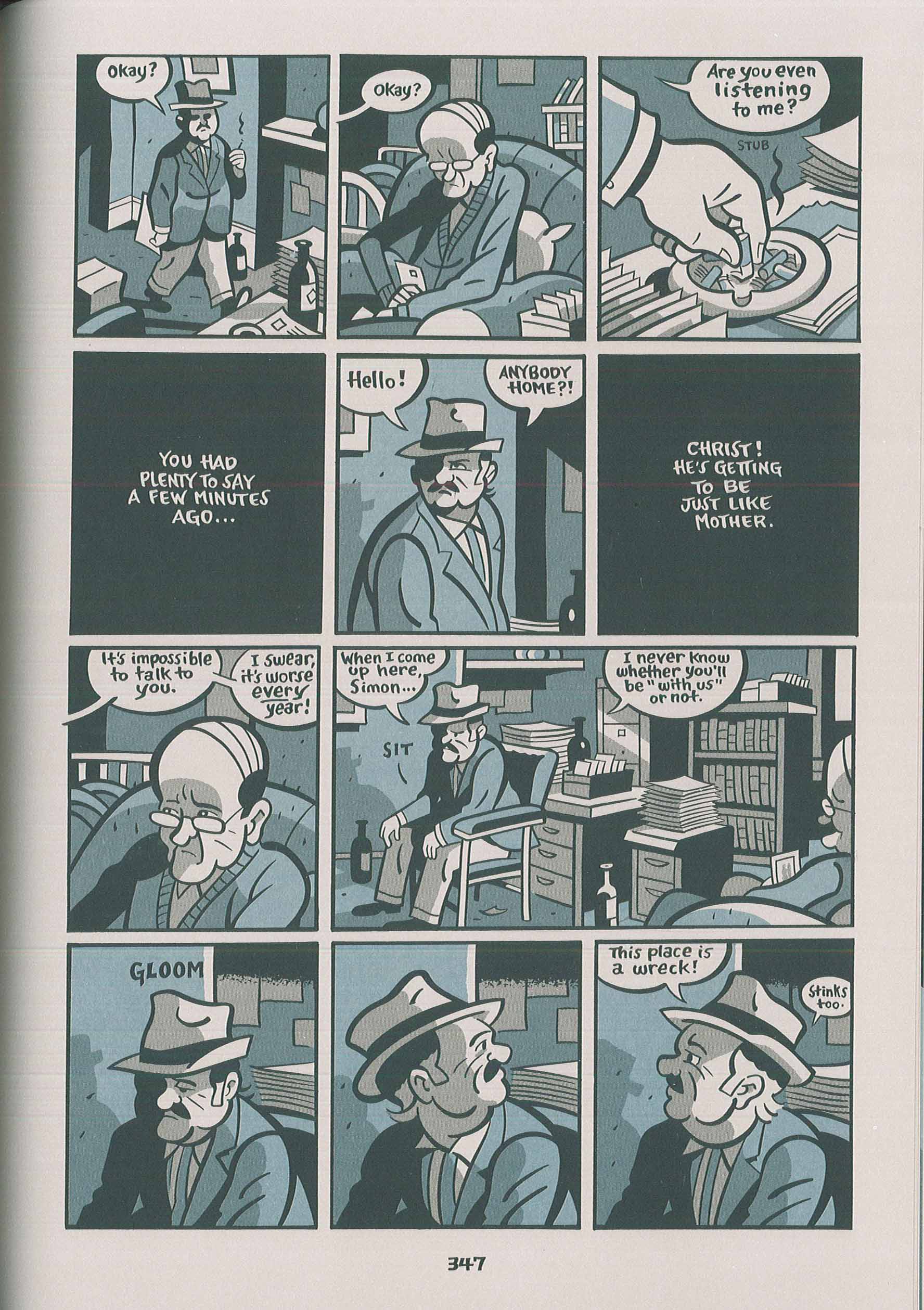

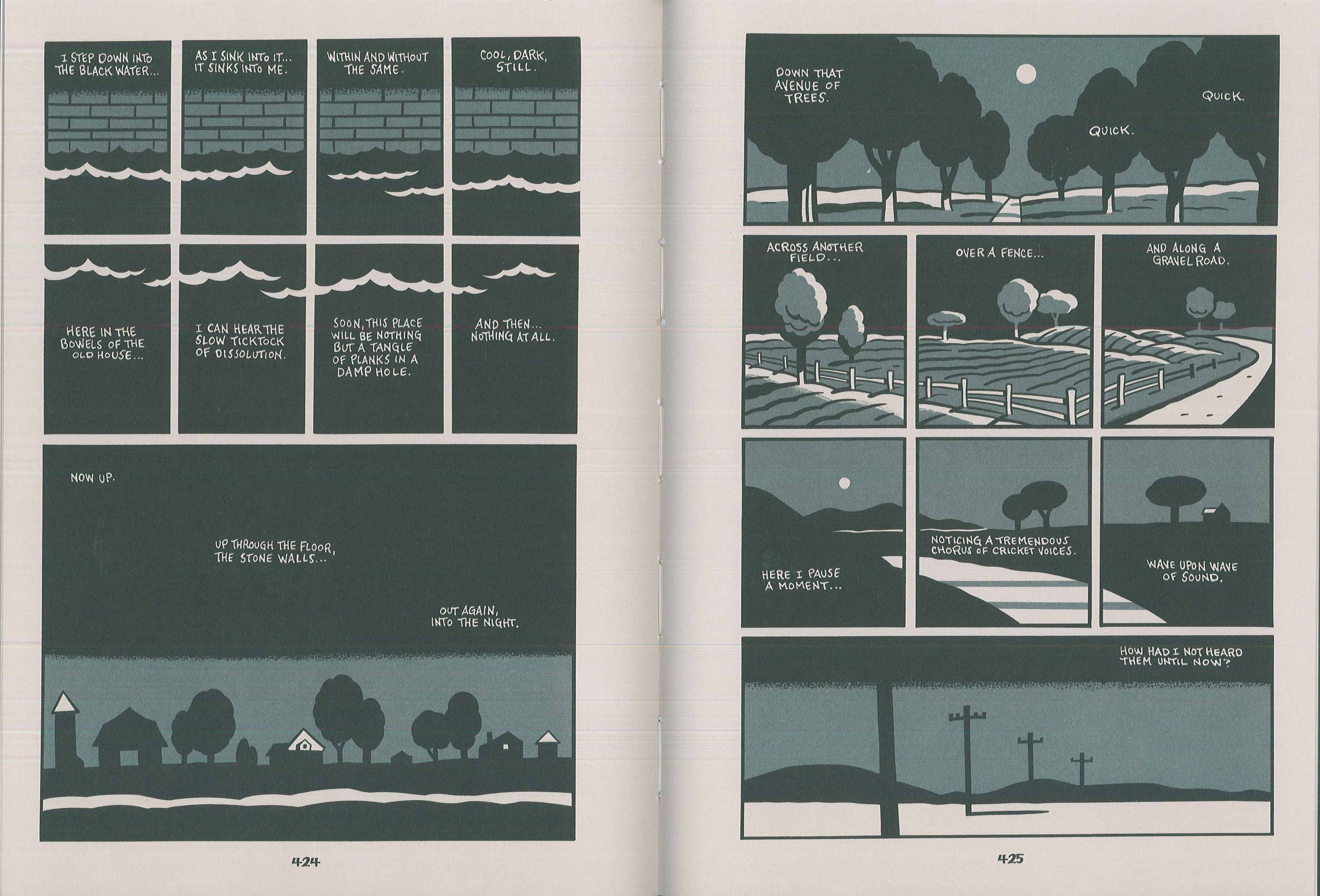

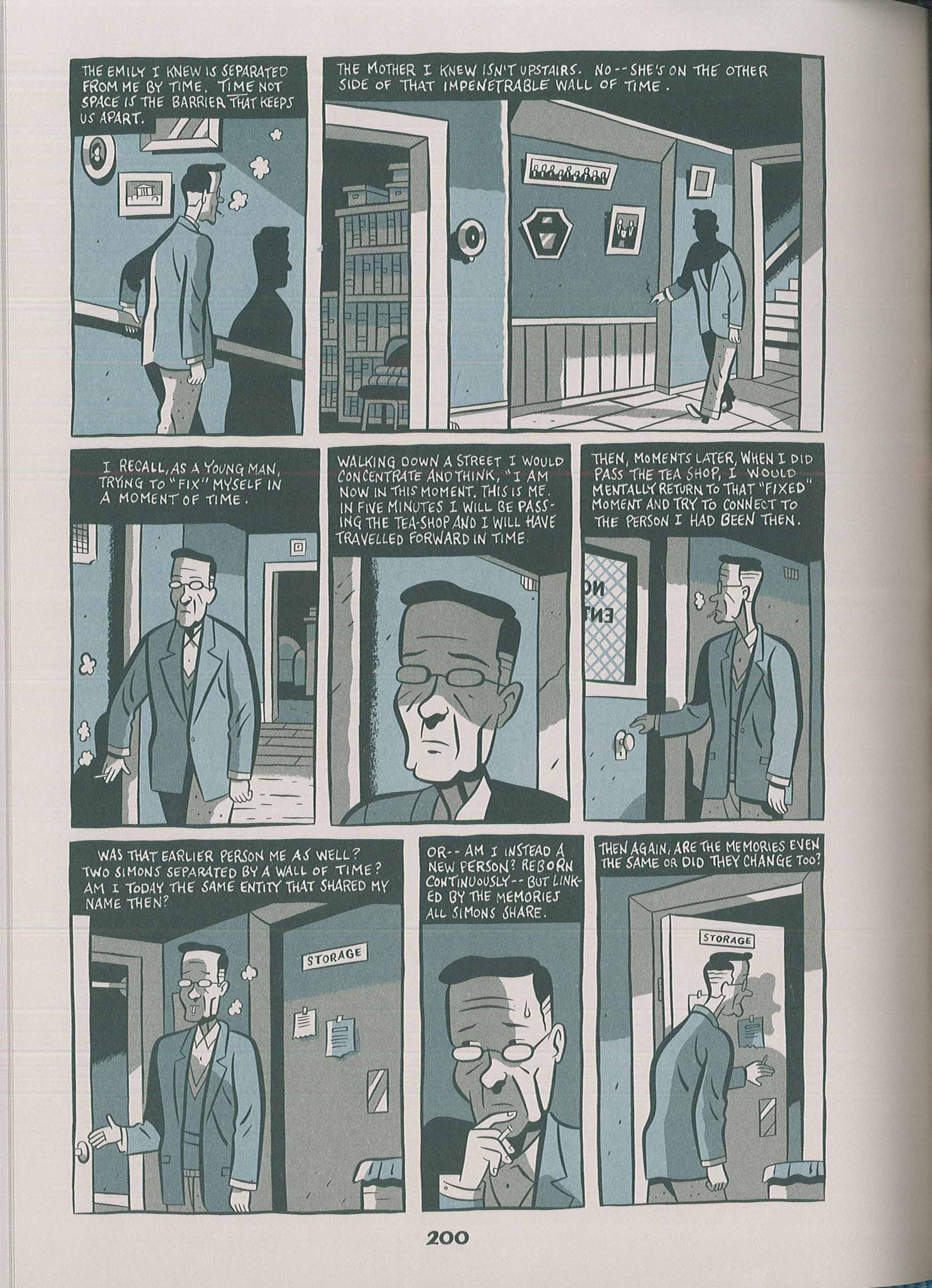

Seth serialized the story on and off for twenty years in his comic book “Palookaville.” Whether you’ve been following the story since its inception and you’re seeing it all in one place for the first time, or whether, like me, you’re new to the story, tracing the evolution of Seth’s visual style is almost as rewarding as reading the story itself. Check out the contrast between the light, thin lines on Seth’s early page above, and the dark, more confident lines on his later page below,

As you can tell from the text on these two pages, these brothers with very different personalities—whom Seth has suggested represent two halves of himself—don’t get along terribly well, which makes for the bulk of the story within this slow, sad, beautiful book. “Clyde Fans” is also about old-school sales and manufacturing, a time when products were still mostly made and sold in person.

Wisely, however, Seth resists the term “nostalgia.” Although he’s fascinated with the stories contained within artifacts from another era, it’s not like he wants to go back to that time—he’s under no illusions that society as a whole was actually better back then. To remind readers of the dangers of nostalgia, he makes a point of illustrating artifacts that belong in places like the Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia. “I don’t want some golden fog of the past,” he told “The Comics Journal” in an interview from early 2018.

But such reminders don’t negate the story’s reverence for a disappearing tactile world that we would do well to preserve. “Clyde Fans” pays tribute to a physical world that fades to too easily to background these days as we slip into the glow of our screens. The book’s design and packaging hold your attention not with bright colors and flash, but with the heft of calm and distinction. The book comes in a slipcase, glossy paper beneath the cut-out window on the cover, and the inside of the box is lined with tan stripes like corrugated cardboard. The whole ritual experience before you’ve read a word is mesmerizing, like falling under the spell of an old Little Golden Book.

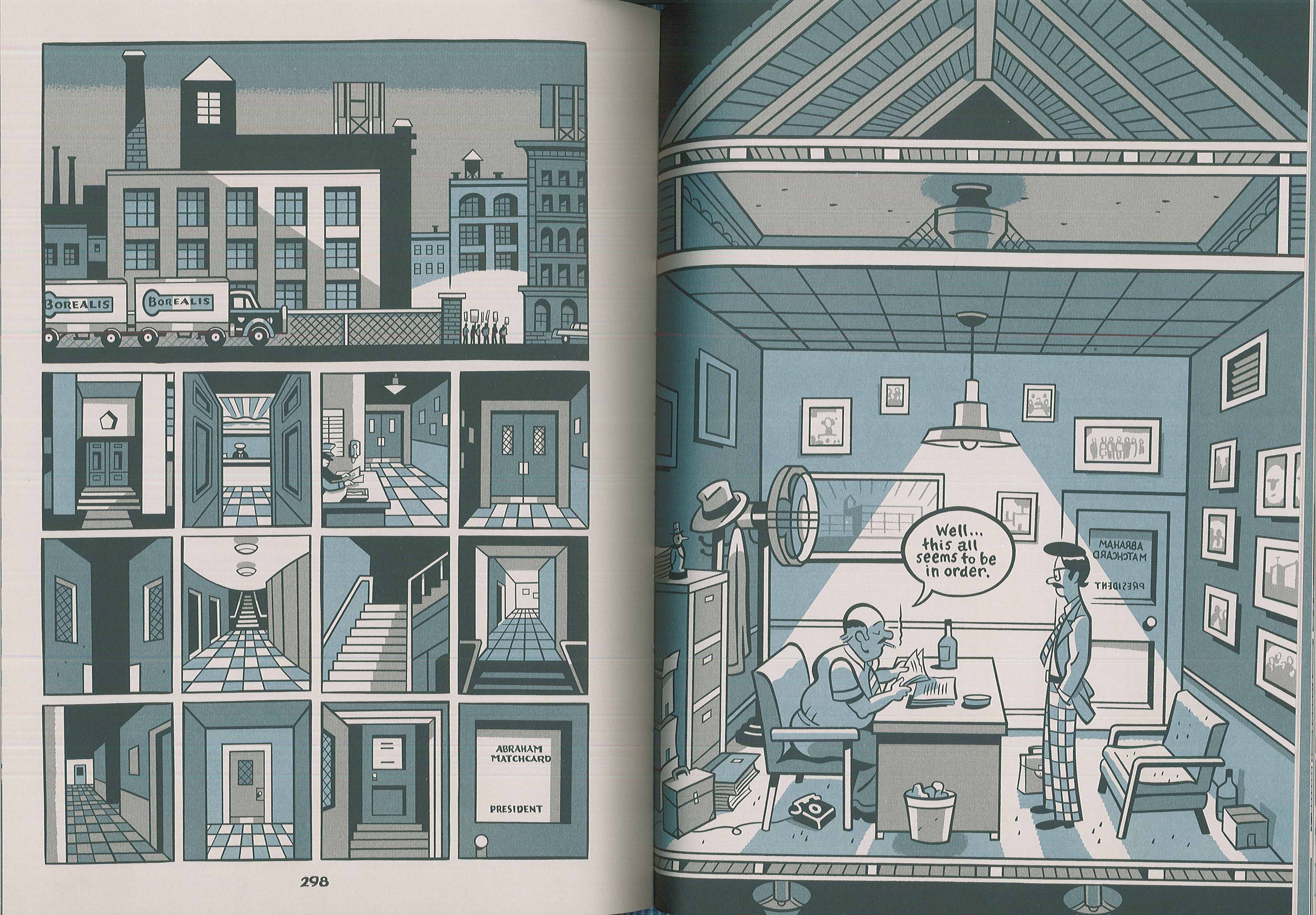

Seth slows down time, space, and movement throughout the book, encouraging readers to notice visual patterns and echoes. In this more blatant example, the obnoxious fashion patterns of the 70s bring together more subtle elements of this two-page spread, not just the checkered floors but also the windows, and even the buildings’ structural elements:

In his most abstract and contemplative scenes, Seth plays with narrative structure as well. The gutters—the white space between the panels that traditionally serve to advance the storyline—sometimes stack rows of panels, and sometimes divide larger pictures, whether a whole page, or, like in this example, long strips of landscape:

Reading Seth is more about the experience of reading comics than about the story itself. Comics scholars love to compare Seth to literary giants like William Faulkner or Marcel Proust, who strive for real-time representation of both the joys and the inherent fallibility of memory and lived experience. As Seth told Derek Royal of “The Comics Alternative,” “I really have had a very small life. If you are going to write about stuff that small, it might be [just] as interesting to talk about how unreliable the memories are. . . . The process of forgetting is certainly much more powerful than the process of memory.”

Here’s the question: is 488 pages of memory and forgetting too slow, too much? Melancholy Simon poses a similar question to the readers as he accesses his mental “storage” space below:

I recommend giving the book a try. Even if you don’t like the story itself, the practice of reading “Clyde Fans” highlights the value of your own memory—especially your tactile memory, which holds up and holds on better than timelines and visual experience. Hence Seth’s collection of rotary phones and other tactile memorabilia in his house, which he’s named “Inkwell’s End.” A pot of ink itself might run out, but not the muscle memory—made luxurious in its recollection—of unscrewing its cap to dip the nib of the pen, scrape the excess liquid on the tub’s glass edge, and set the pen to page to scrape and scratch its way into a story.