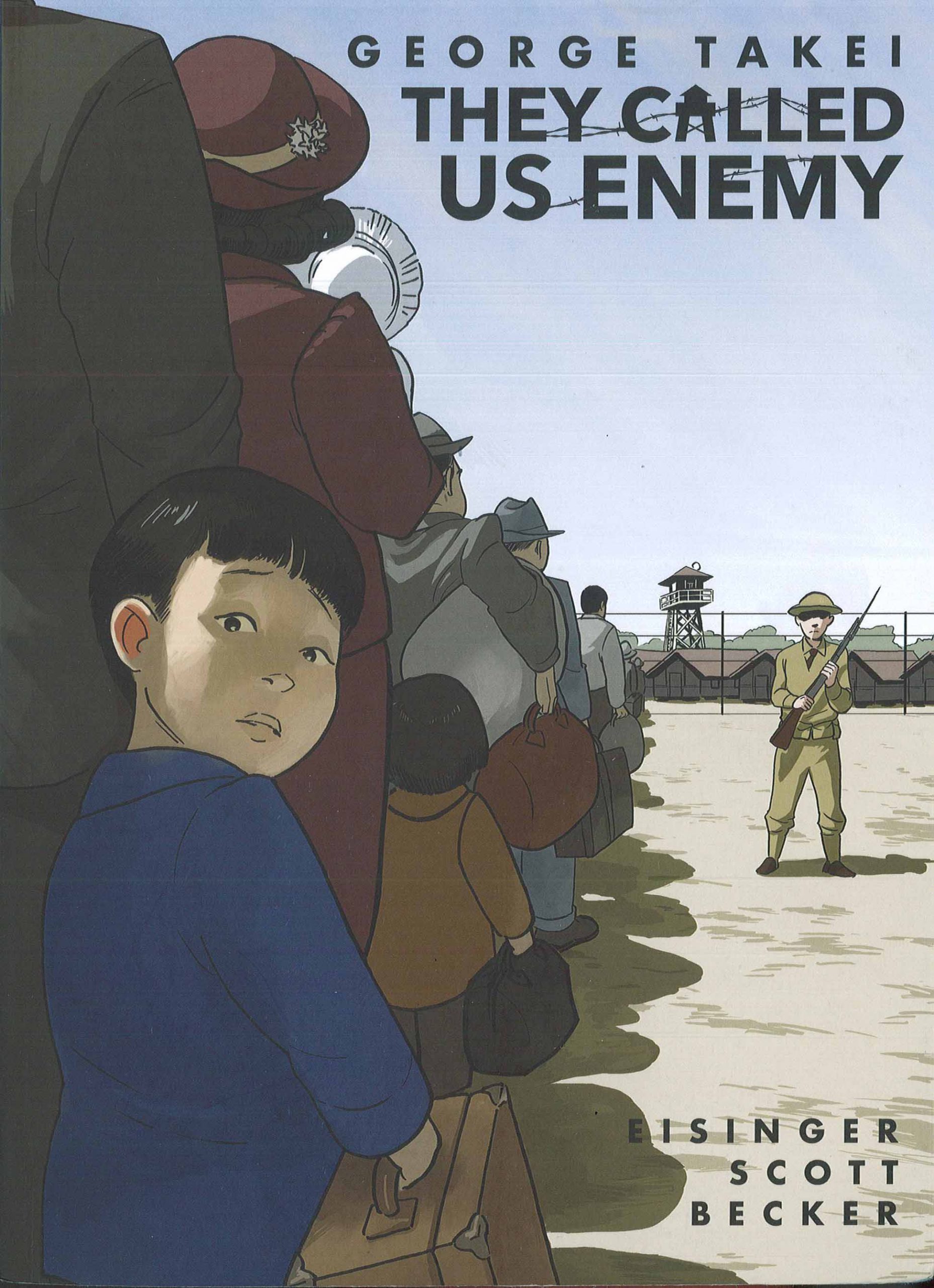

“They Called Us Enemy” by George Takei, with Justin Eisinger, Steven Scott, and Harmony Becker. Top Shelf, July 2019. 208 pp. Paperback, $19.99. Middle to high school.

Thanks to Fables Books, 215 South Main Street in downtown Goshen, Indiana, for providing Commons Comics with books to review. Visit the store or contact them at fablesbooks@gmail.com to find or order this or any book reviewed on this blog.

How do you decide whether to stand for your principles or protect your family? It’s not a decision any parent should be forced to make, but actor and activist George Takei lived the consequences of his parents’ honesty. Fortunately for Takei—and for his massive fanbase, many of whom have followed him from the first “Star Trek” to his more recent roles in shows from “Furturama” and “Archer” to “Kim Possible”—he not only survived, but eventually thrived.

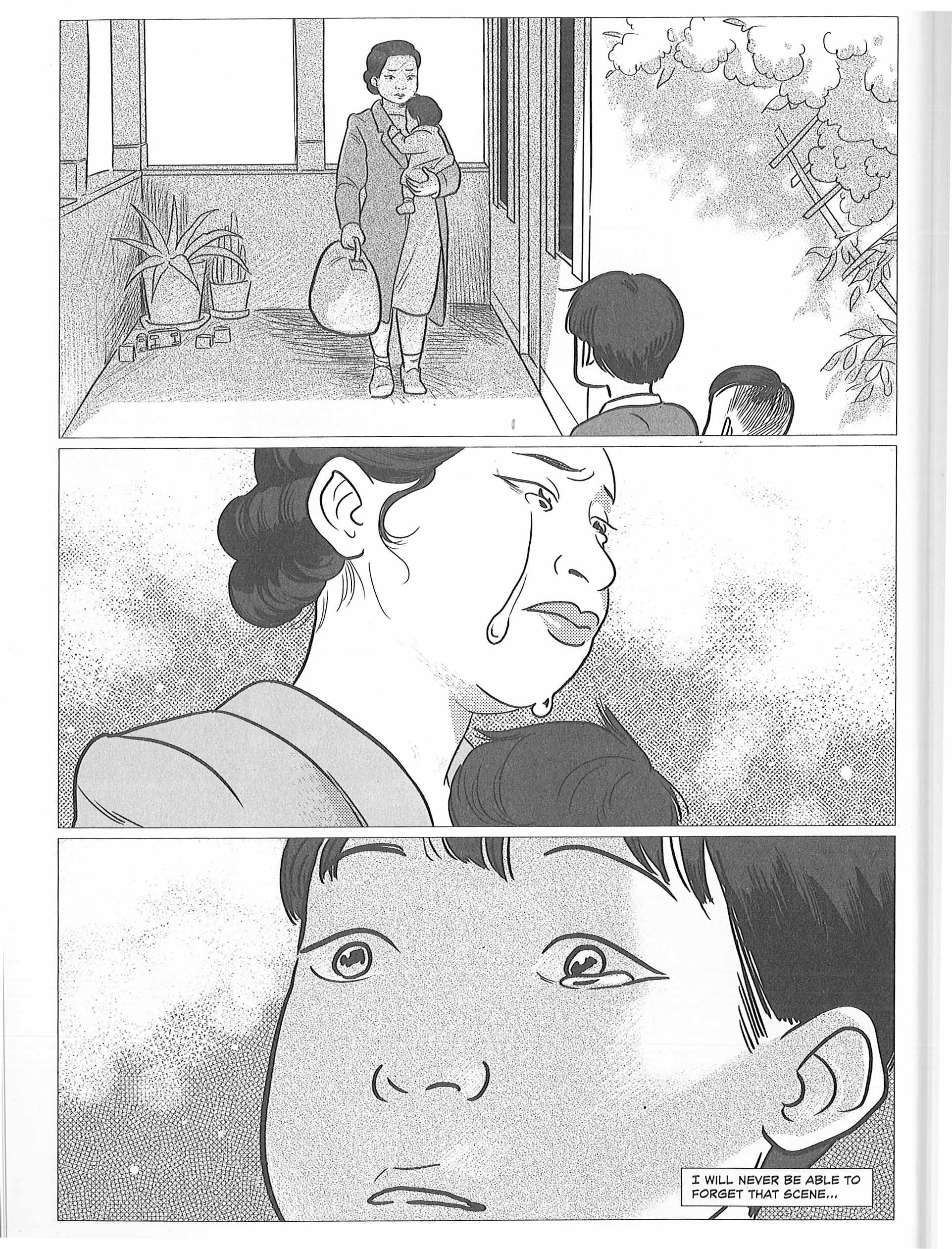

Now 82, this isn’t the first time that Takei has told the story of his family’s time in US internment camps for Japanese Americans. His memoir “To the Stars” also inspired the musical, “Allegiance.” The graphic memoir “They Called Us Enemy” is the most recent version of this thankfully brief chapter in his life, published by Top Shelf, best known for US congressman John Lewis’s graphic memoir trilogy “March.” Co-writers Justin Eisinger and Steven Scott helped Takei translate the narrative to comics form, and the art of Harmony Becker—subtle and manga-inflected (see, for example, the backgrounds and the giant tears on the page below)—transforms the story into a work of art.

When Takei and his family were first imprisoned in May 1942, they didn’t have any choices to make at all: US soldiers came to the door with bayonets to kick them out of their house. They had ten minutes to pack.

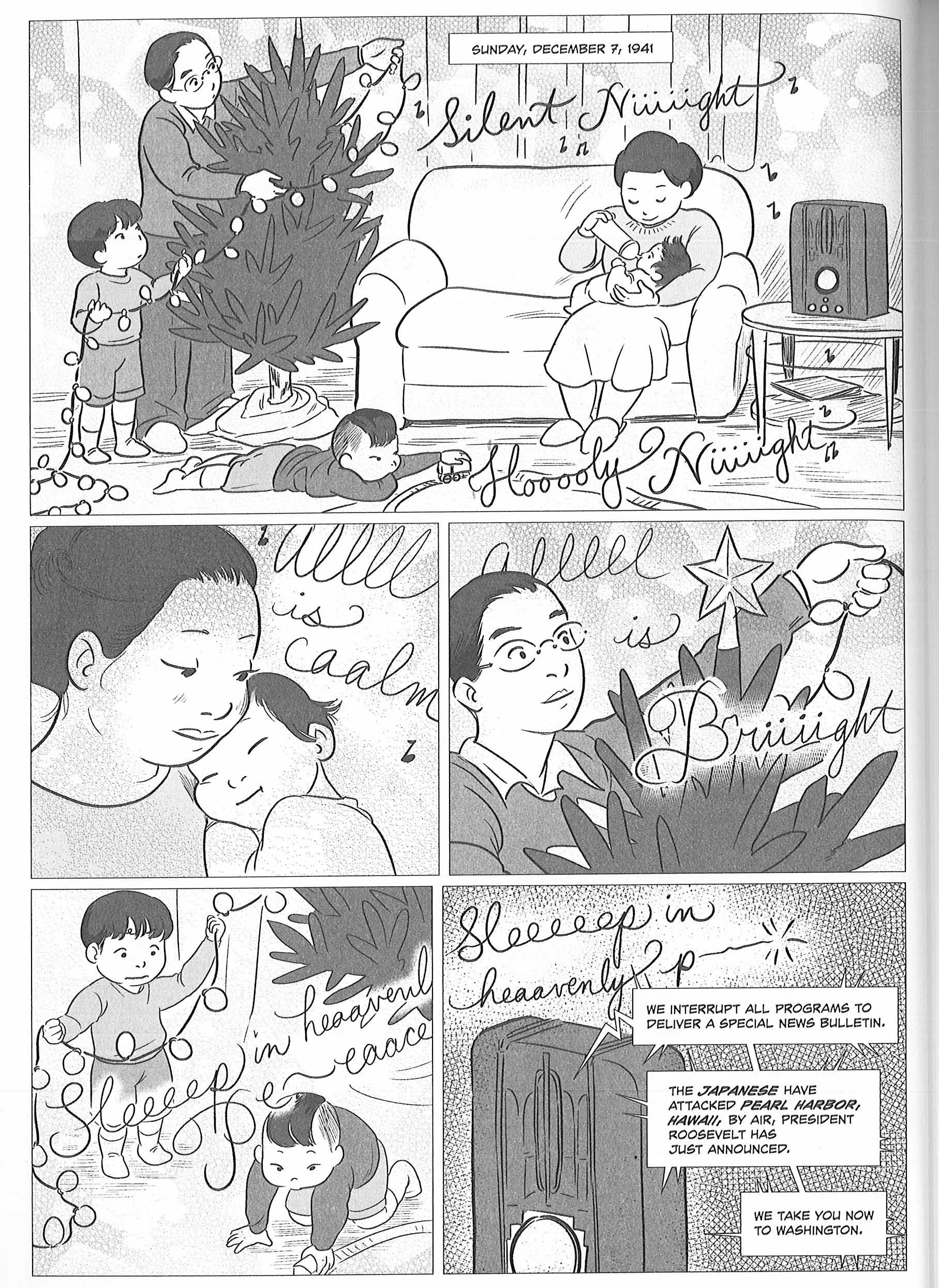

Takei’s mom and his two siblings were all born in the US, and his father had started his own business and lived here for decades. Like many Americans, they first heard about the surprise bombing of Pearl Harbor by Japanese planes in early December 1941, while they were decorating their Christmas tree.

Little did they know how much and how fast their lives would change. As Takei explained in a 2014 interview for “Democracy Now,” “[W]e were citizens of this country. We had nothing to do with the war. We simply happened to look like the people that bombed Pearl Harbor.”

A few months later in May 1942—right after Takei had celebrated his fifth birthday—he and the rest of his family had to leave everything behind except a couple of suitcases and his mom’s smuggled sewing machine. They had been swept up by the wave of anti-Japanese sentiment that accompanied the US entry into World War II. Forced from their home at gunpoint, they felt lucky to get five dollars for their car, and one dollar for their brand new refrigerator before they were sent to a temporary internment location. They never got that house back.

The family lived out the first few weeks of their imprisonment in horse stalls at California’s Santa Anita racetrack. As Takei recalls in a 2014 interview for the Pryor Center at the University of Arkansas, “for my parents it was a degrading, humiliating, anguishing moment. But the memory I have is ‘We get to sleep where the horsies sleep.’” The multiple camps that would eventually house 120,000 innocent Japanese Americans hadn’t yet been built.

Takei and his family were eventually taken to Camp Rohwrer in Arkansas, one of ten internment sites nationwide. Rohwrer held just under 8,500 people when it was full. The train that took them there was guarded by armed soldiers, and they were required to keep the window shades down when they stopped. Was this rule to help the US government hide its wrongdoing, or to protect these passengers from the racist sentiment sweeping the nation? Probably for both reasons, and both reasons also highlight why the history of these camps has long been kept under wraps and out of US history books.

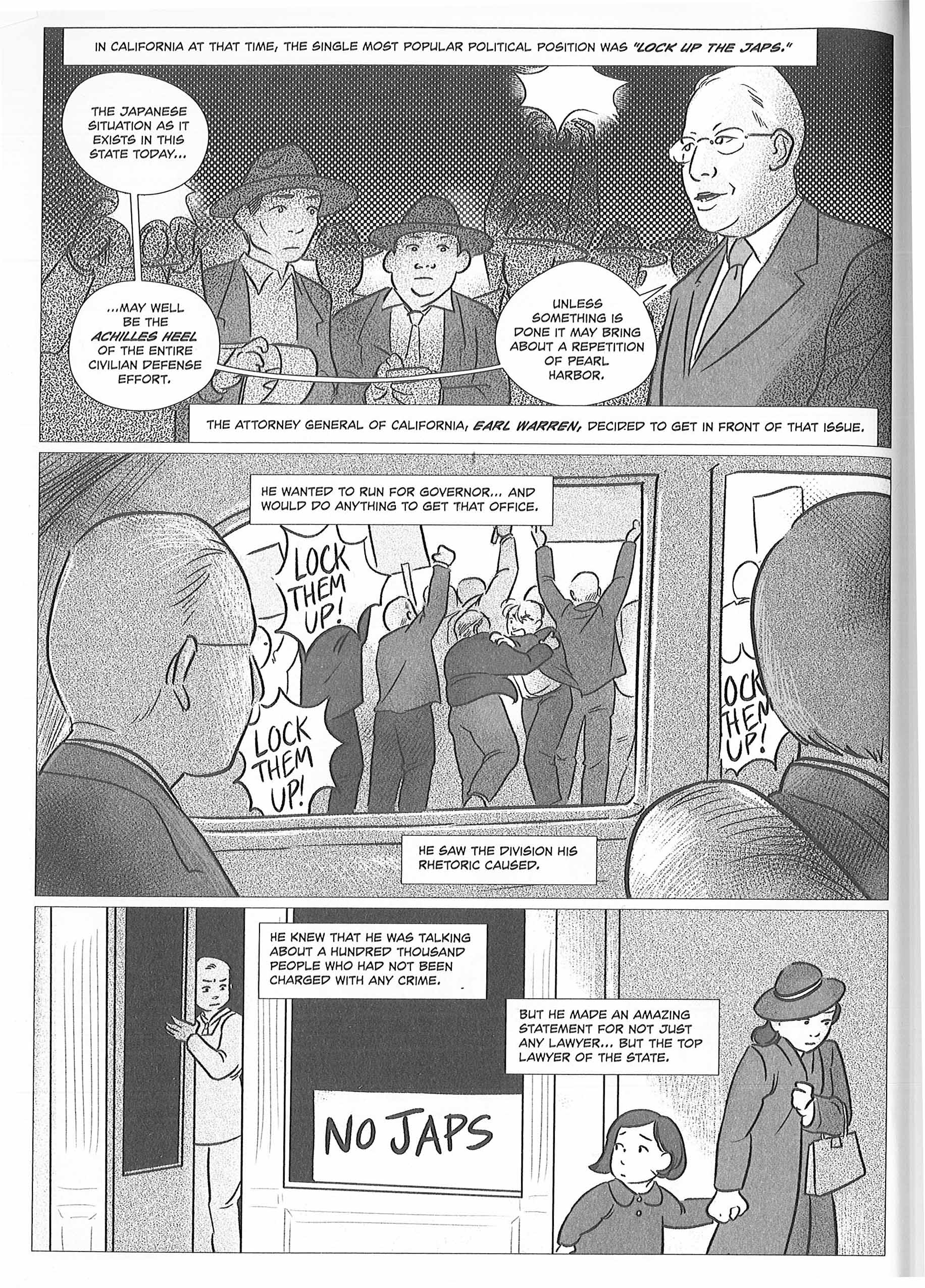

Takei doesn’t shy away from connections between his family’s experience in the 1940s and current events. Below, for example, amidst the same chants that reverberate through crowds at hate-filled rallies today, he shows how national paranoia was whipped into a frenzy. Earl Warren—yes, that Earl Warren, future liberal Supreme Court justice—was then California Attorney General, and was particularly eager to harness that frenzy into fuel for a bid for the governorship:

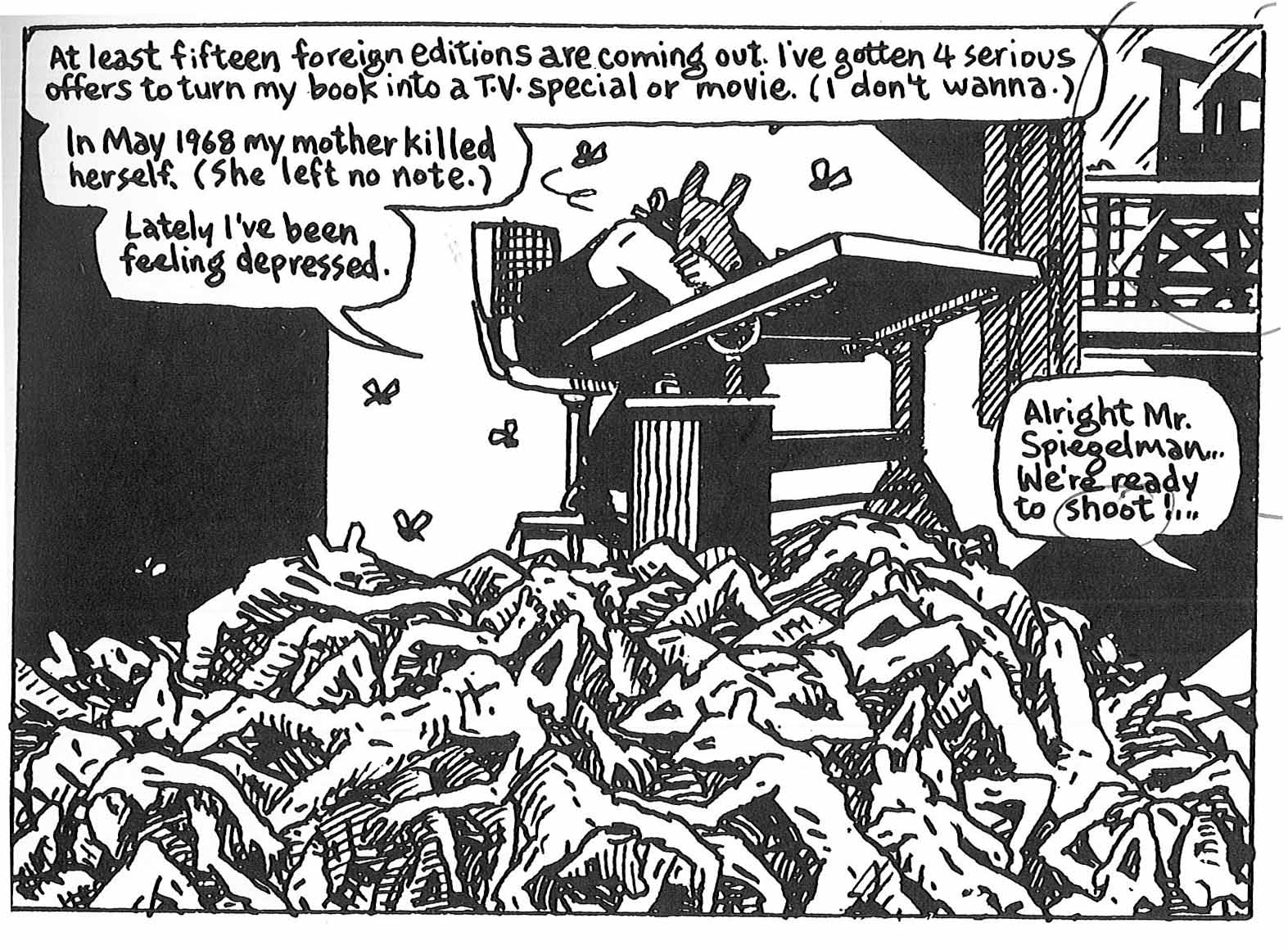

Looming large as an influence in this story is Art Spiegelman’s groundbreaking narrative “Maus,” about his father’s time in Nazi concentration camps. “Maus,” which in 1986 was the first graphic memoir to win the Pulitzer Prize, arguably paved the way for this book, and Becker’s illustrations repeatedly though subtly highlight Takei’s debt to Spiegelman, most notably by placing watchtowers in the corners of the panels—a visual echo that will especially resonate with fans of the genre.

From “Maus II,” by Art Spiegelman

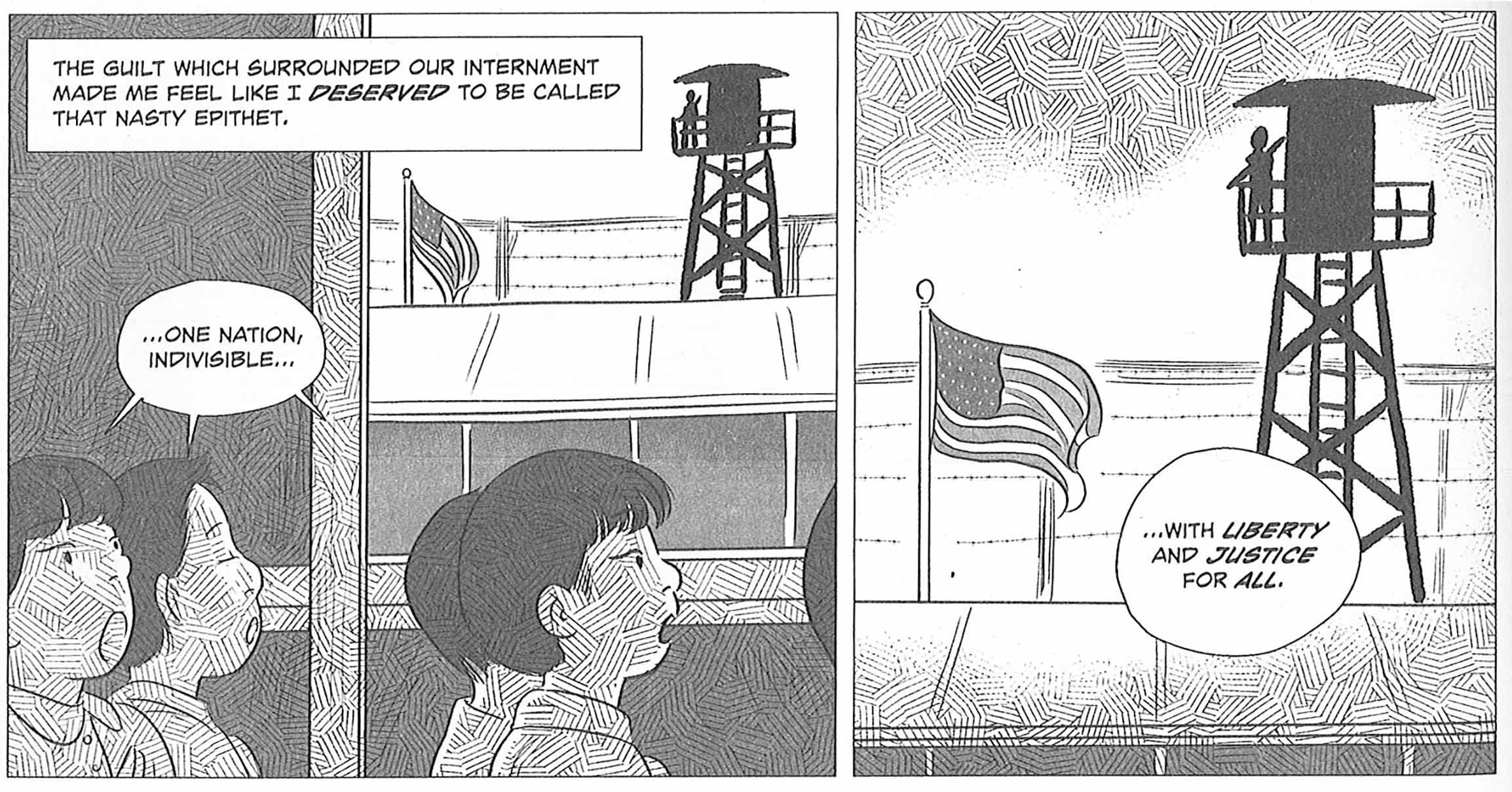

Takei fumes over being called “Jap Boy” by a teacher after his release, but also references the watchtower—a repeated image, just like in “Maus” (the cover is another example, among many more)—to illustrate his internalization of the experience. Becker’s structure and layout convey what words would only obscure.

Takei and Becker are not saying that these internment camps were as horrifying as Nazi concentration camps in Europe. But with this two-panel visual punch, they drive home the point that that Takei’s experience happened on our soil. The hope is that they also instill a conviction—in their young readers, especially—that such injustice should never happen here again.

Becker’s illustrations in general are so subtle that their craft and brilliance are easy to miss. The texturing not only of backgrounds but also of foregrounds (look carefully at the faces and walls in the image above) make each repeated reading richer than the first. Becker’s deft shifts in camera angles and frames also maintain buoyancy in the educational sections of the narrative, which could easily be weighed down by words.

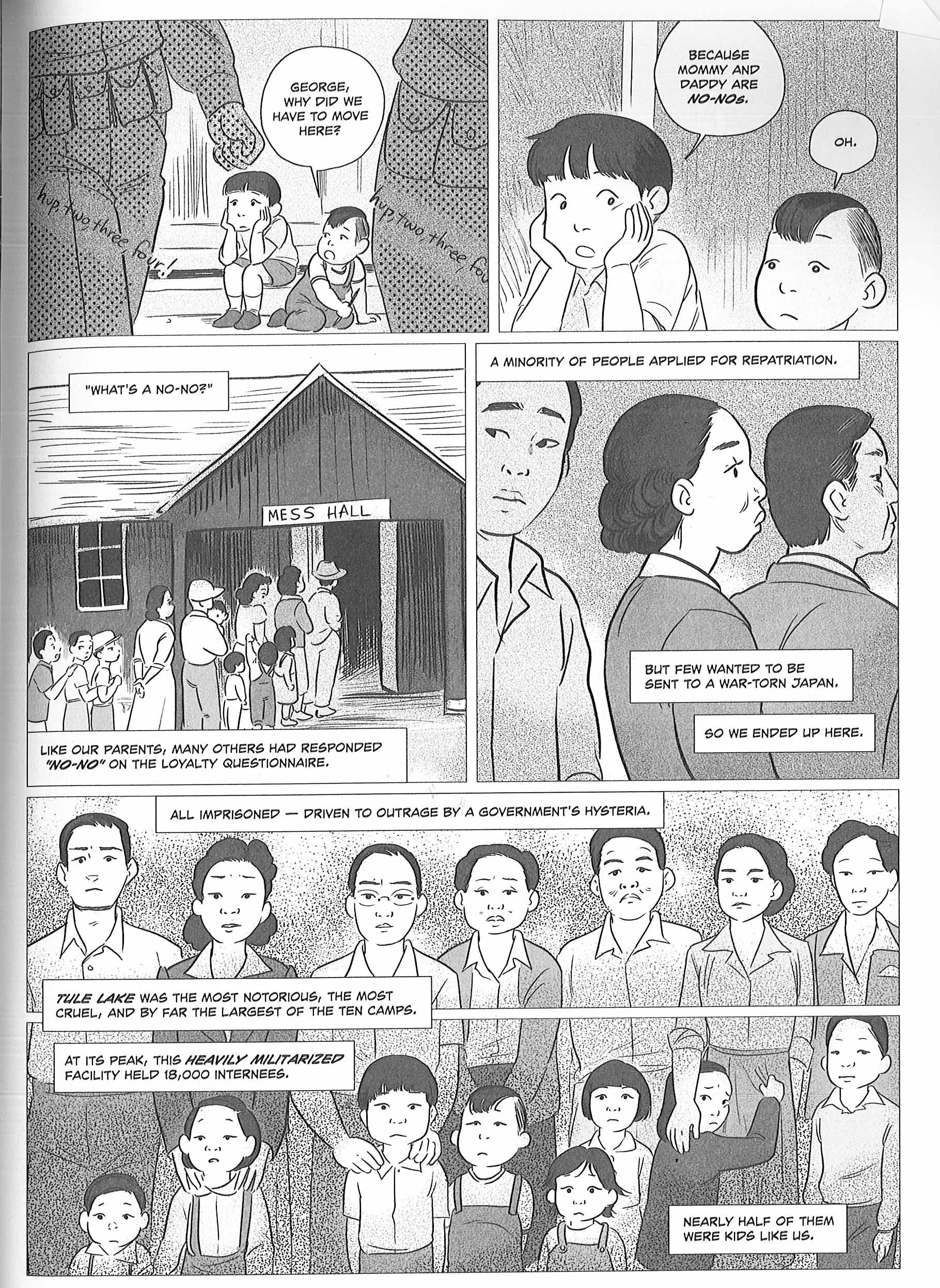

After being transferred to Tule Lake—a second, harsher camp back in California—for answering honestly on a “loyalty questionnaire” with a built-in catch 22, Takei and his family almost lose hope. Again, Becker doesn’t over-draw. At this narrative turn for the worse, the extra, otherwise unnecessary gutter that splits the bottom panel across the torsos of the adults trying to hold things together says enough:

Most striking in this book overall is the optimism of Takei and his parents. The story highlights many adults who did their best to protect imprisoned kids both physically and emotionally: a visiting Santa Claus at Rohwer and a Quaker who risked his life to deliver books to Tule Lake. Takei also acknowledges the ways that the whole country was suffering during World War II: As he found out on a visit to Arkansas as an adult, the families on the other side of the barbed wire were envious of the prisoners, because residents of the camps had access to three meals a day.

It wasn’t until later, as a teenager, that Takei began to understand the depth of the horrors his parents went through. Yet his father continued to defend the worth of his country of choice. As Takei explained in the “Democracy Now” interview, “my father told me that our democracy is very fragile, but it is a true people’s democracy, both as strong and as great as the people can be, [and] also as fallible as people are.”

If anyone had a right to throw up their hands in frustration and renounce their citizenship, it would be Takei and his family. But they not only believed in our unique democracy, they also found ways to keep it on track. Takei, especially, has been outspoken in his activism for gay rights, as well as for the rights of families imprisoned at our southern border.

Right now, as I type this review, those families are suffering what Takei and his family suffered, and worse. If Takei and his family could not only survive, but channel that resilience into action for positive change, the rest of us can too.