“When Stars Are Scattered,” by Victoria Jamieson and Omar Mohamed. Color by Iman Geddy. Dial Books for Young Readers, April 2020. 264 pp. Paperback, $12.99. Recommended for ages 9-12, although my eight-year-old loved it, and I’m way older than 12 and loved it, too.

Thanks to Fables Books, 215 South Main Street in downtown Goshen, Indiana, for providing Commons Comics with books to review.

COVID-19 PROTOCOL: Please wear a mask as required by local mandate, and follow store guidelines. You may enter at either the front or back entrances. High risk customers can still make browsing appointments before or after hours, and all customers can continue to order online at fablesbooks.com, over the phone 574-534-1984, or via email fablesbooks@gmail.com.

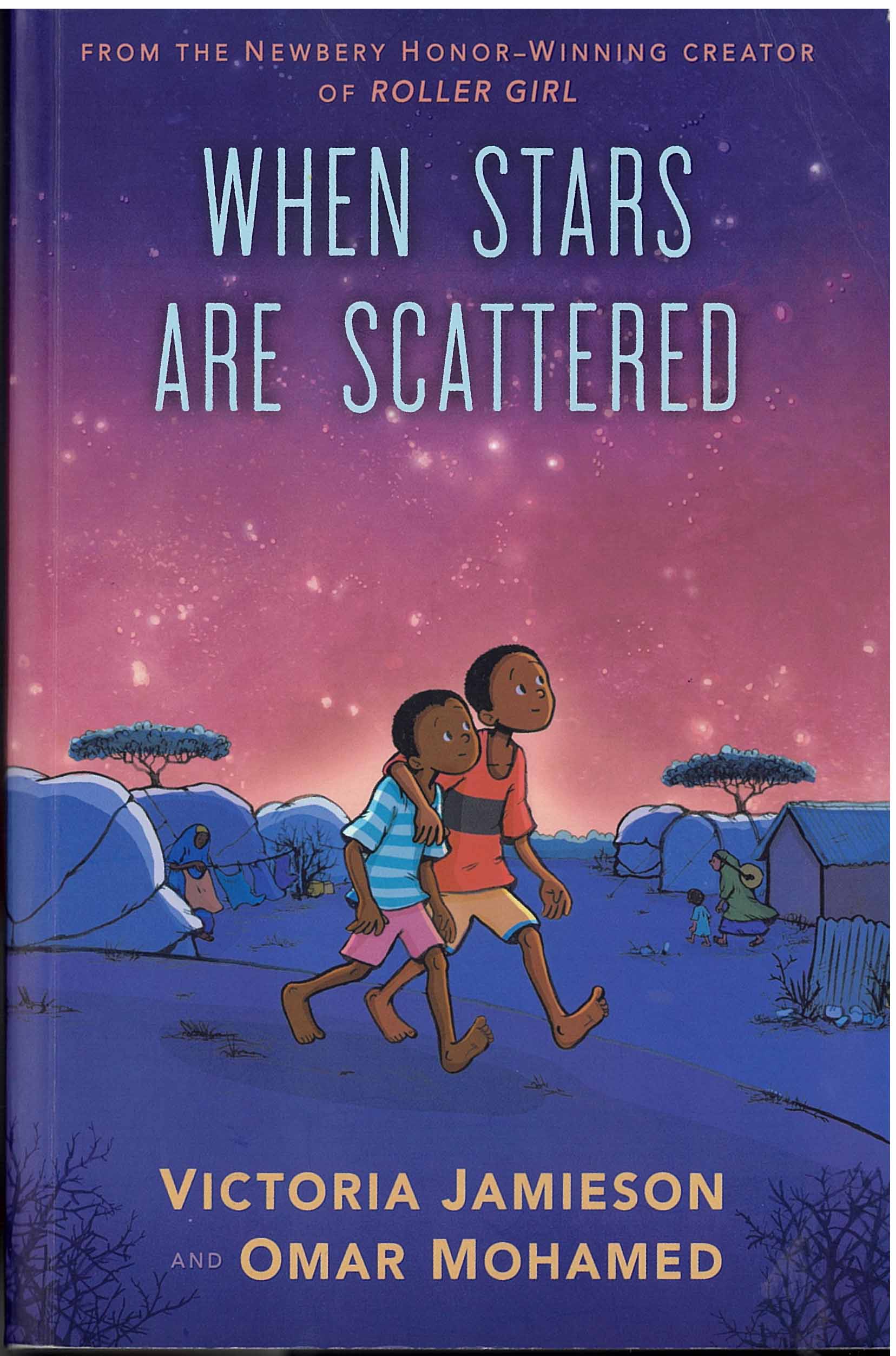

This story has a happy ending. But it’s not an easy road there. “When Stars Are Scattered” is a true story narrated by Somalian refugee Omar Mohamed, the book’s co-author. Mohamed and his younger brother Hassan, grew up and lived for fifteen years in Dadaab, a Kenyan refugee camp, before finally being cleared to resettle in America. Awash in bright colors, Dadaab looks like a fairy-tale landscape:

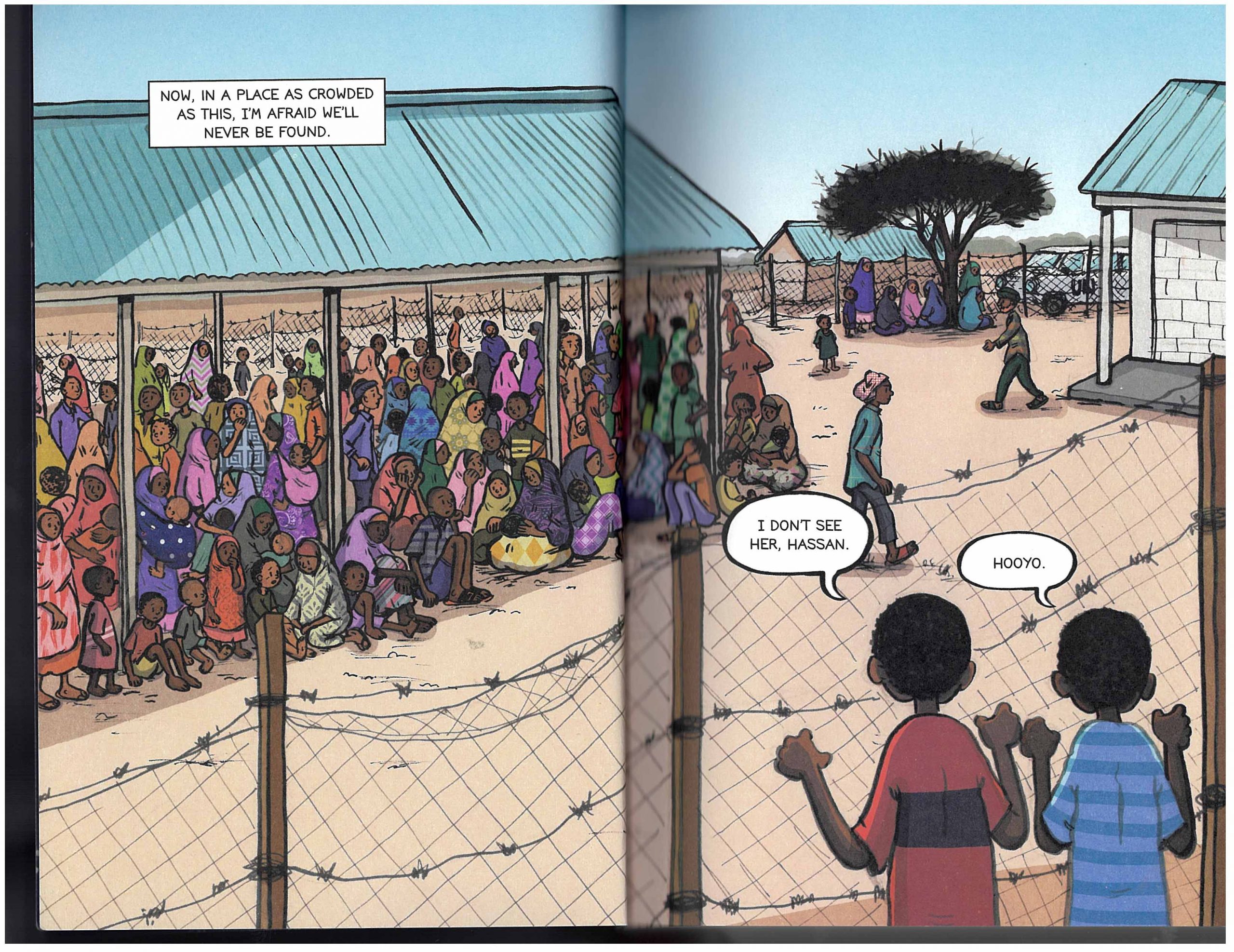

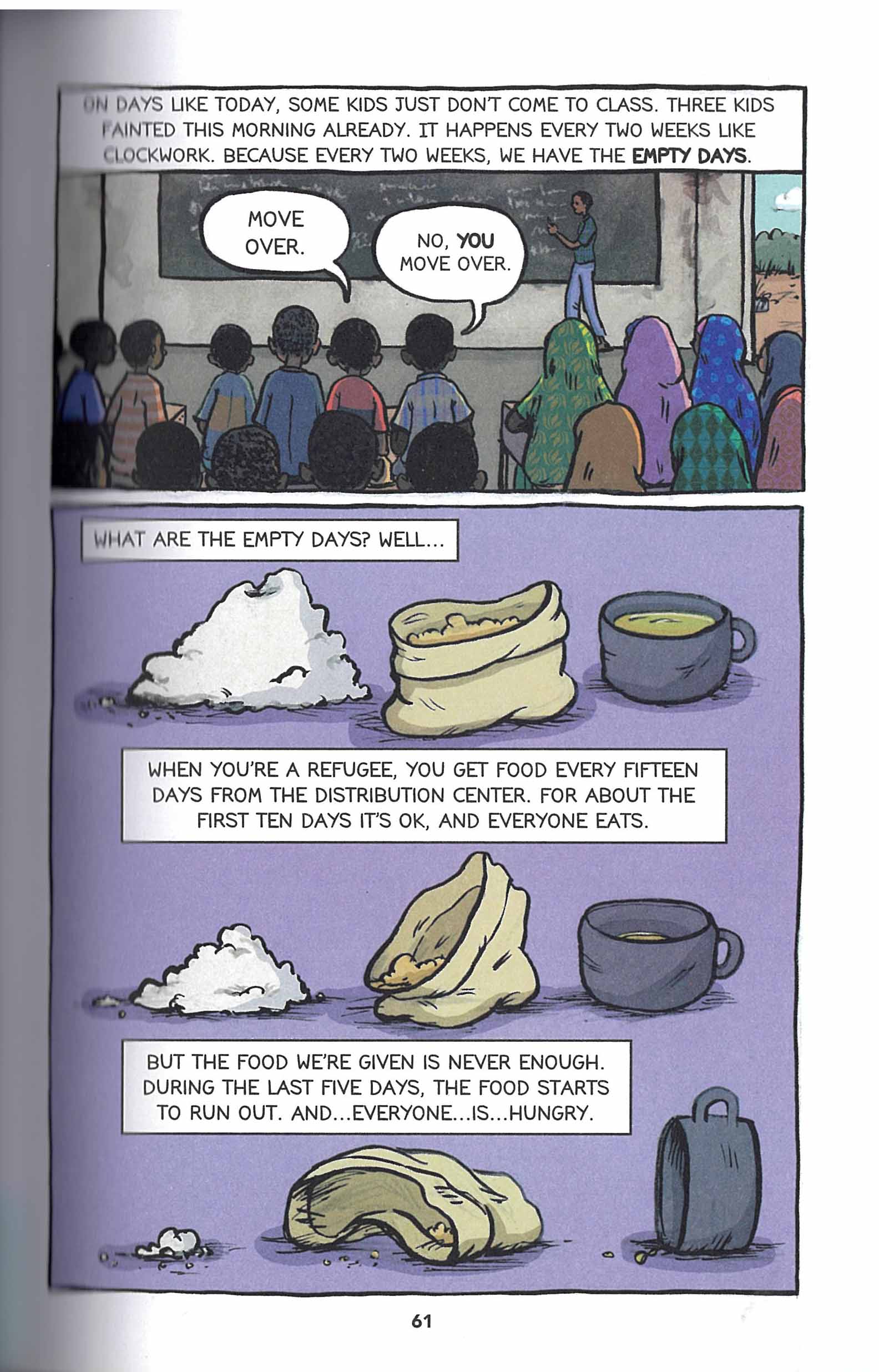

Yet as the narration conveys in matter-of-fact prose, Omar and his younger brother Hassan lead a more than challenging life. This stunning opening spread depicts the boys’ regular ritual of searching new arrivals at the camp for their mother. When Omar was only four, his father was killed by “angry men” and their mother sent Omar and his baby brother to flee Somalia. As if the thought of a four-year-old tasked with protecting his brother on their escape through a war-ravaged country isn’t difficult enough to process, readers discover a few pages later that Omar and Hassan have been conducting this same search for their mother over and over for years—the seven years that they’ve been living in what was supposed to be a temporary camp. Omar doesn’t spend much time bemoaning his daily struggle, instead delivering straightforward lines like, “We don’t have any food to eat tonight, so Hassan and I go right to bed,” and narrating simple yet powerful images like this explanation of “empty days”:

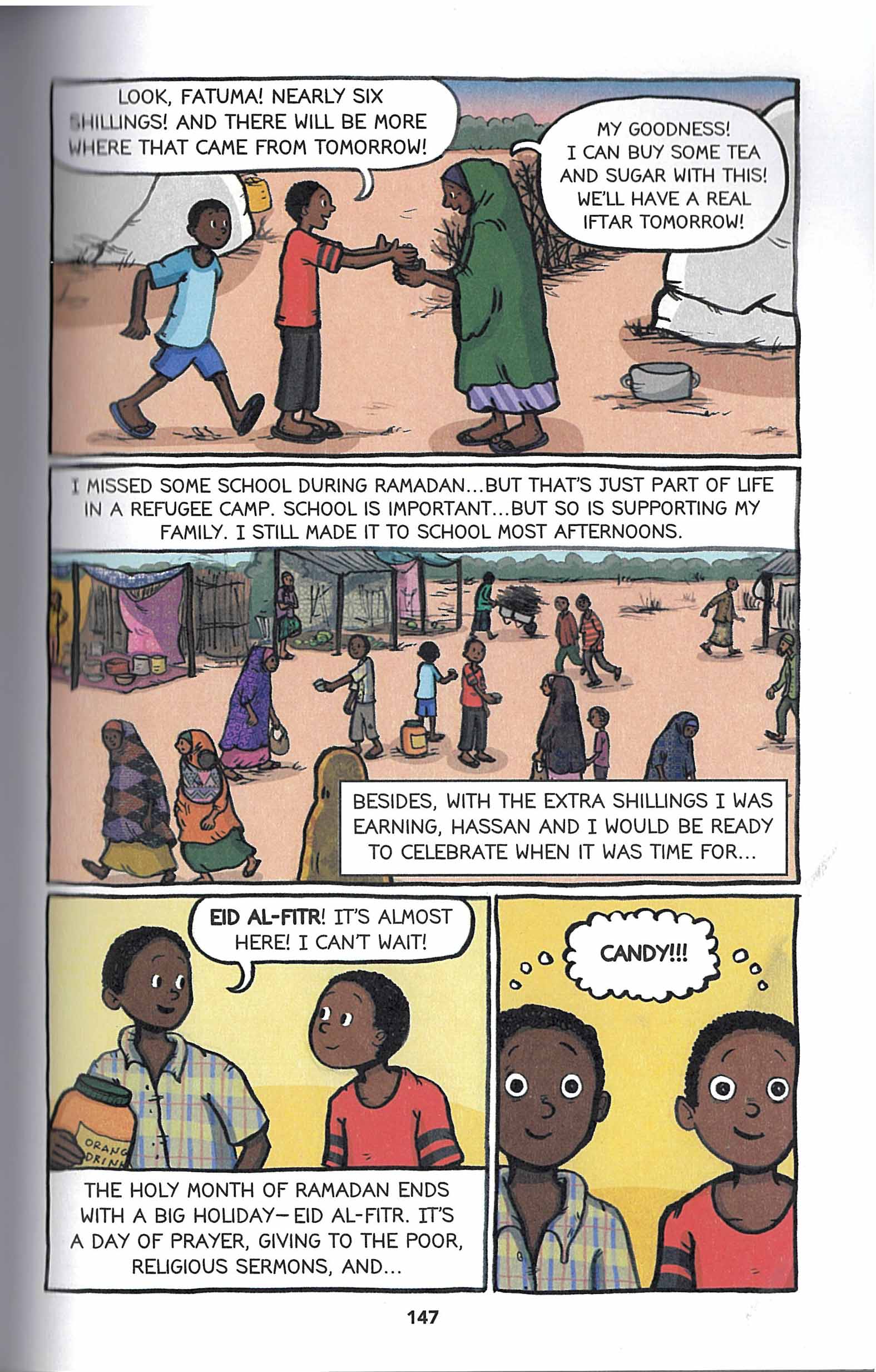

Stories like Omar and Hassan’s are important for kids to read: they need to know that there are worlds outside of their own, whether nearby or on a different continent, in which the comforts they’re accustomed to can be hard to come by. Yet telling kids to eat their spinach because there’s a hungry kid their age on a different continent isn’t a terribly effective means of building compassion. Fortunately, Mohamed’s co-author and artist, Young Adult comics veteran and Newberry Award winner Victoria Jamieson, knows how to connect with her young readers no matter the content of the story. Seeing Omar and Hassan light up at the promise of holiday candy? Now, that’s something kids can relate to:

Jamieson also pulls out plenty of humorous moments from Omar’s life to keep kids reading. At the start of the story, rather than going to school, Omar is spending his days tending Hassan, who has a mental disability—yet another challenging facet of Omar’s life. Yet Hassan’s introduction is one of my 8- and 10-year-old boys’ favorite part of the story, because Omar explains how he spends a lot of his energy as a big brother trying to keep Hassan clothed. “Truth be told, Hassan would rather be pants-less,” Omar narrates, atop panels of Hassan gleeful, running away from Omar, who holds up a pair of pants like a bullfighter’s muleta.

As hard as some of this story is, readers do know, even in the darkest sections of the book, that things turn out okay: after all, one of the boys has become a co-author of the book. Things turned out more than okay, actually: as we find out in an epilogue, not only did Mohamed earn a college degree after he arrived in the U.S., he also started his own nonprofit called Refugee Strong to support kids in Dadaab, especially girls, who have a harder time staying in school.

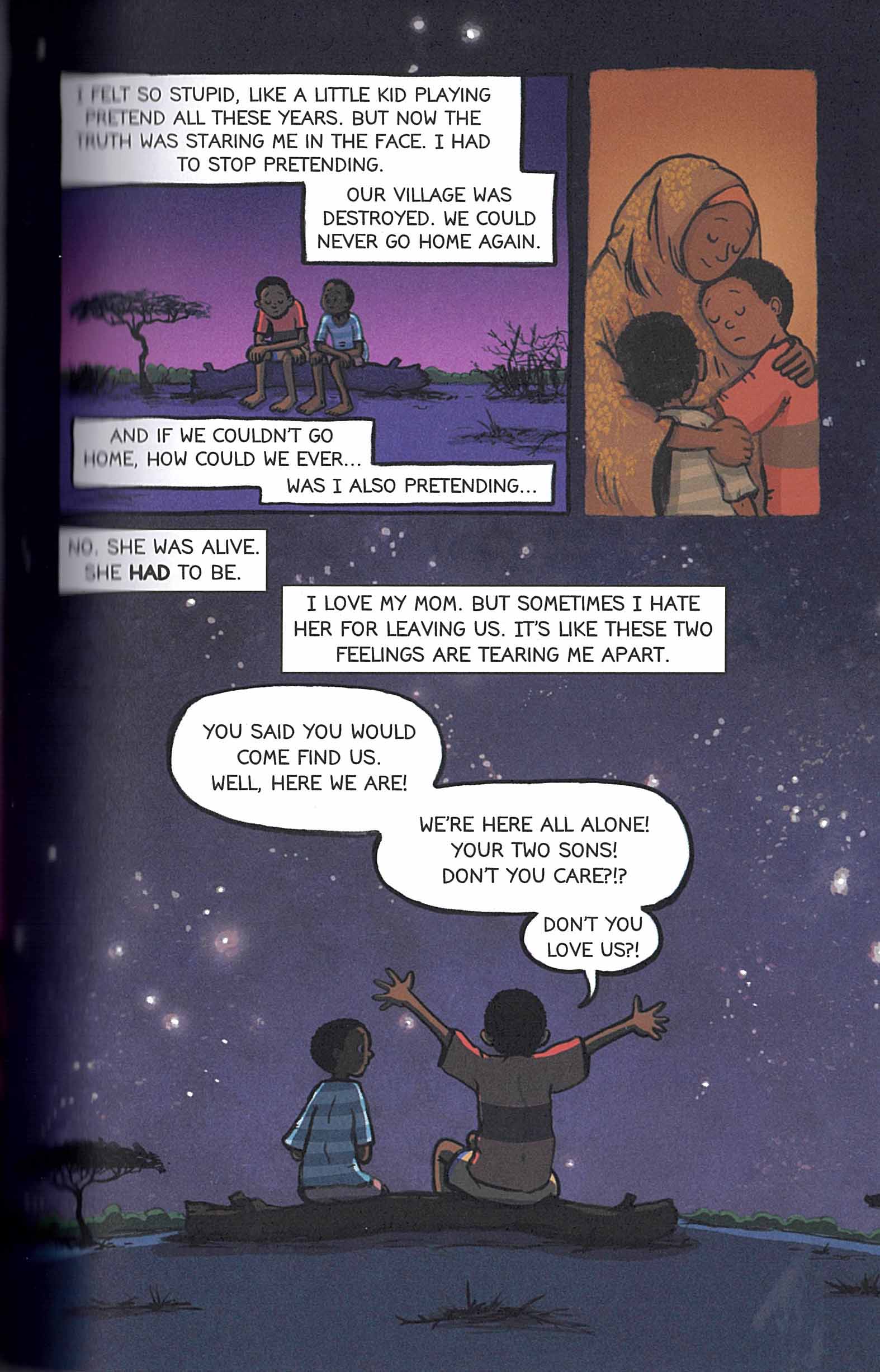

Young and old readers alike will wonder at young Omar’s patience and determination, and question whether or not they would be able to do the same if their roles were switched. Mohamed and Jamieson make it clear, however, that Omar’s resolve does flag at times, as he tries to make sense of a violent and unfair world:

That rusty golden dream panel of the boys reunited with their mom them makes me choke up every time I see it, and threatens to make my own hope flag. Working, parenting, and staying sane during COVID can seem hard enough. If I got separated from my sons, would I be able to make my way back to them? Yet as Mohamed pleads to his young readers especially in the book’s end note, “Please take away from the reading of this book an understanding that you should never give up hope.”