“Cartooning is a form of world-making,” reads the introductory text to the current comics exhibit at Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art. Museum exhibits create immersive worlds, too, and I highly recommend three mini comics worlds contained in Chicago, listed below in order of how soon they’re going to disappear:

“Chicago Comics: 1960 to Now,” Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) https://mcachicago.org/Exhibitions/2021/Chicago-Comics-1960s-To-Now, $15, through October 3

“Marvel Universe of Super Heroes,” Museum of Science and Industry https://www.msichicago.org/explore/whats-here/exhibits/marvel-universe-of-super-heroes/, $18, in addition to standard admission, through October 24 (some weekends are sold out)

“Chicago: Where Comics Came to Life (1880-1960),” Chicago Cultural Center, plus BONUS: MCA overflow exhibit in the Buddy space on the first floor, https://www.chicago.gov/city/en/depts/dca/supp_info/comics.html, free, limited hours, through January 9

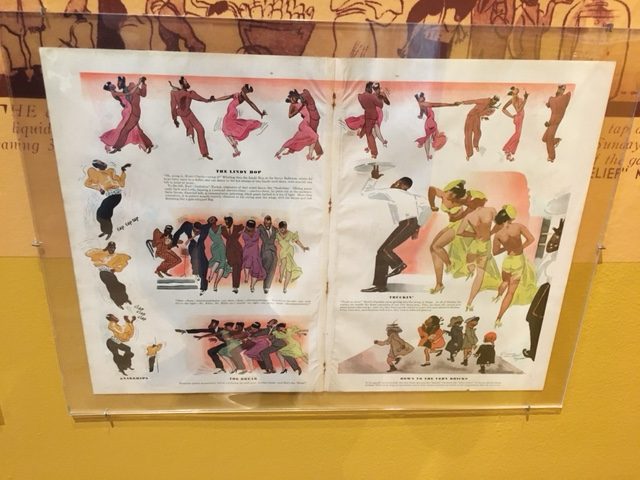

If you’re not familiar with Chicago comics, your first question might be, why Chicago rather than the coasts? The Cultural Center exhibit delves into the industrial history that made Chicago a national center of paper production in the mid-1800s, saving publishers in the Midwest and west from having to import paper from east coast mills. This foundational shift in supply lines led not only to a fount of newspapers in Chicago, but also to the freedom to innovate, especially evident in the weird, edgy, and experimental comics produced by publications like the Tribune and the African-American Chicago Defender.

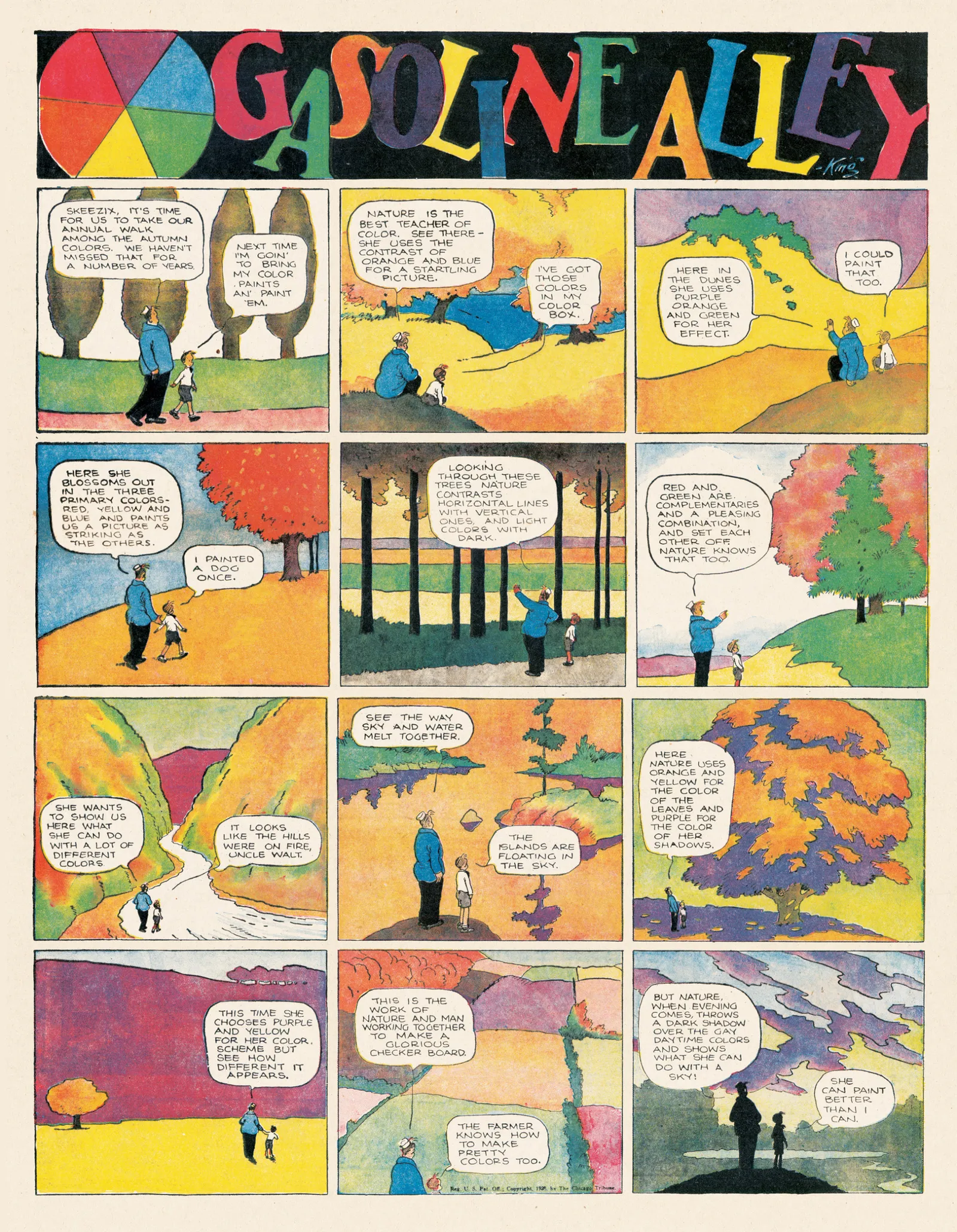

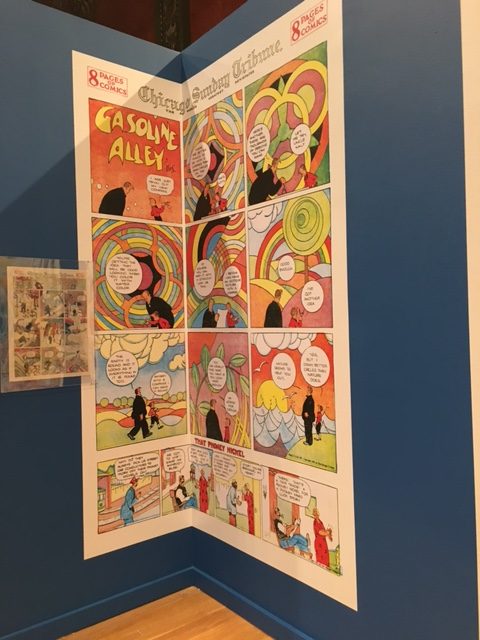

As acclaimed Chicago cartoonist and co-curator Chris Ware explains in a recent New Yorker article, technical innovations also fueled the development of groundbreaking comics in Chicago papers. A Chicago engraver in the late 1800s first developed the ability to insert images within columns of newspaper text, and color printing techniques developed and continued to improve, eventually leading to stunning visual explosions like this:

Ware also posits a more philosophical answer to the Why Chicago? question. Because comics harness the interplay between word and image to create their own language, Ware suggests, “No-bullshit Chicago” itself is geographically poised to negotiate the tension between the two modes of communication, “situated halfway between the coast of reading (New York) and the coast of seeing (Los Angeles).”

It’s so easy to get immersed in “Chicago: Where Comics Came to Life (1880-1960),” that you might forget it’s all contained within a single room. Ware and his co-curator, Chicago’s recently retired cultural historian, Tim Samuelson, masterfully shoehorned so much information into this room, there’s a good chance you might run out of time (as I did—heads up that the exhibit room closes at 3:45).

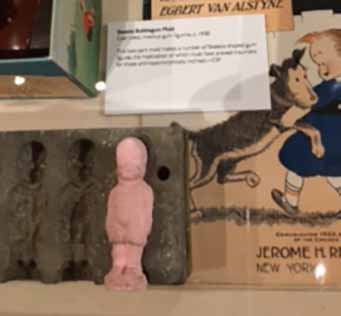

If you do find yourself only halfway through at 3:30, I recommend searching out the information tags labeled “CW.” Much like Ware’s comics, his summaries and explanatory labels toggle between wry, wistful, and philosophical. Witness the tag that accompanies this bizarre artifact from the heyday of Frank King’s “Gasoline Alley”:

“This two-part mold makes a number of Skeezix-shaped gum figures,” the tag usefully explains, then veers into the interstices of Ware’s benevolently twisted brain by adding, “the mastication of which must have proved traumatic for those anthropomorphically inclined.”

I’m still reeling from the information density of this exhibit. Much of my education was about early comics artists I knew a bit about, but not a lot. That list includes the first syndicated Black female cartoonist Jackie Ormes (also featured in the MCA exhibit); George Herriman, the creator of Krazy Kat; Winsor McCay of early experimental serial comic Little Nemo fame; and Dale Messick, creator of Brenda Starr, who was the first syndicated female cartoonist in the U.S.

I also learned names that I wasn’t familiar with, but won’t soon forget, everyone from production gurus like Chicago Tribune editor Mollie Slott, and early artists whose names may be slipping out of familiarity, but whose work you will likely recognize once you see it: Harry Hershfield, Billy DeBeck, Virginia Huget, and E. Simms Campbell.

Because my own work in comics focuses mostly on the past couple of decades, what I especially enjoyed about this exhibit was visual confirmation of the roots many current comics luminaries: R. Crumb’s “Mr. Natural” prefigured in the huge feet of Billy DeBeck’s characters, for example, or Chris Ware’s hyper-detailed comics mazes in a visually and intellectually layered Kin-der-Kids spread.

This exhibit also makes clear that comics that might seem groundbreaking today were building and riffing on previous decades of experimentation and innovation.

Reading the Sunday Funnies as a kid, I always passed over Frank King’s “Gasoline Alley,” which I’m now embarrassed to say seemed boring, lost in a world for which I had no context. After taking in this exhibit, I now agree with Ware that Gasoline Alley is best understood as an extended graphic novel, reflecting daily life back at its readers with a beauty and intensity to help them pause, look up from their newspapers, and appreciate it.

As Ware explains on one Gasoline Alley exhibit tag: “Seven random daily strips, like seven days of the week, highlight the passing years and moments that Frank King tried to capture and pin down in his work. Thing is, we all do the same thing every day—but most of us just don’t write it down.”

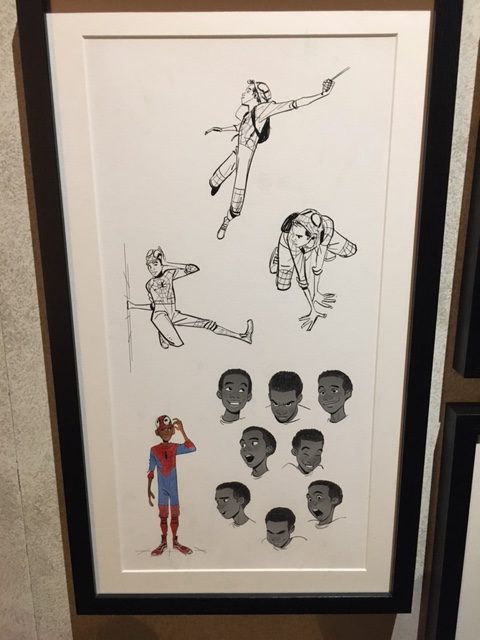

“Chicago Comics: 1960 to Now” at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA), the companion exhibit to Ware and Samuelson’s, is, as might be expected, more edgy than contemplative. The exhibit is especially invested in exploring Chicago’s brilliant and distinct underground comics scene, as well as political strips from publications like the Defender. Featuring work by over forty comics artists, in addition to sketches, production pages, and other rare archival material, illustration models and various other constructions by many of the artists are also on display:

The exhibit is brilliantly designed. These and other quirky constructions—which the artists sometimes created as illustration aids, as a means through artistic blocks, and sometimes just because—are interspersed between pages that take more reading and concentration to absorb.

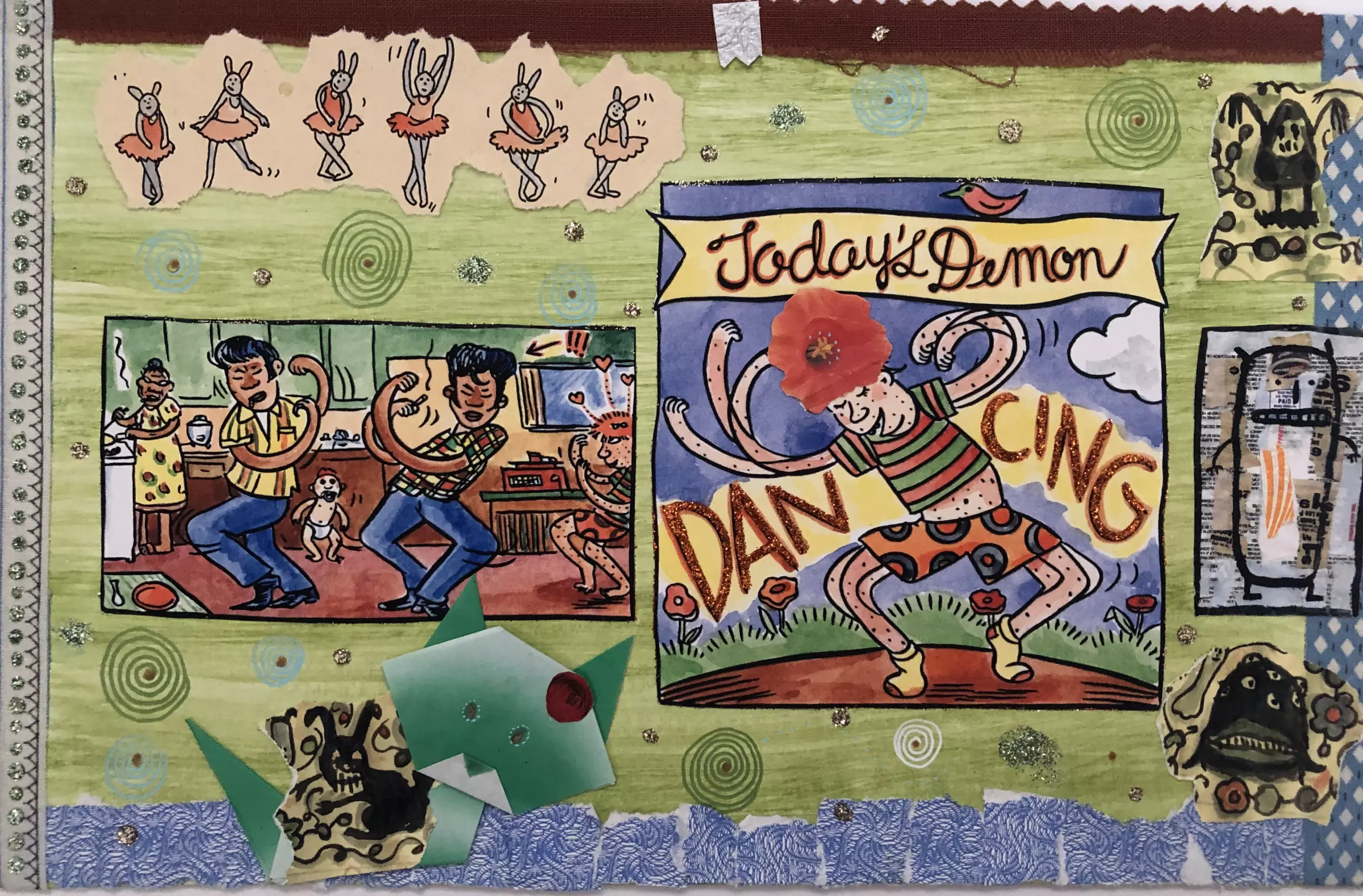

This fangirl was especially thrilled to see the deeply textured original pages of works like Lynda Barry’s 100 Demons, her lush dark mirror of perky scrapbooking trends in the U.S.:

Other artists’ original contributions show them experimenting with different materials, like the glass paintings of Nick Drnaso of “Sabrina” fame:

The exhibit wraps up with recent artists like Lilli Carré, Eric J. Garcia, and Bianca Xunise, who expertly and unapologetically negotiate comics’ tricky balance between art and political commentary.

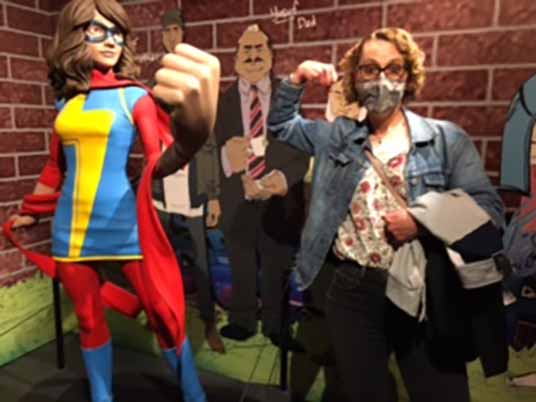

I have less to say about the Marvel exhibit at the Museum of Science and Industry, but that doesn’t make it any less worth the trip. This show is more viscerally immersive, teeming with costumes and fun photo ops.

Do be aware that the Marvel show is an add-on to an already expensive ticket—expensive for good reason, because this is a hands-on kids’ museum that strives to awe kids into scientific interest—but whether or not you have kids, if you’re a superhero fan, it’s worth the trip.

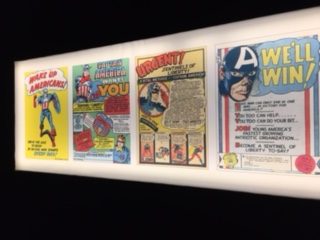

The tags are designed to teach kids about the history of comics, and engage them in the production process via the characters they love. That said, if you already know a lot about comics, the exhibit might not teach you anything new, but the history and memorabilia are both fascinating, and just plain exciting to see in person, like this Captain America plug for kids to get involved in the war effort:

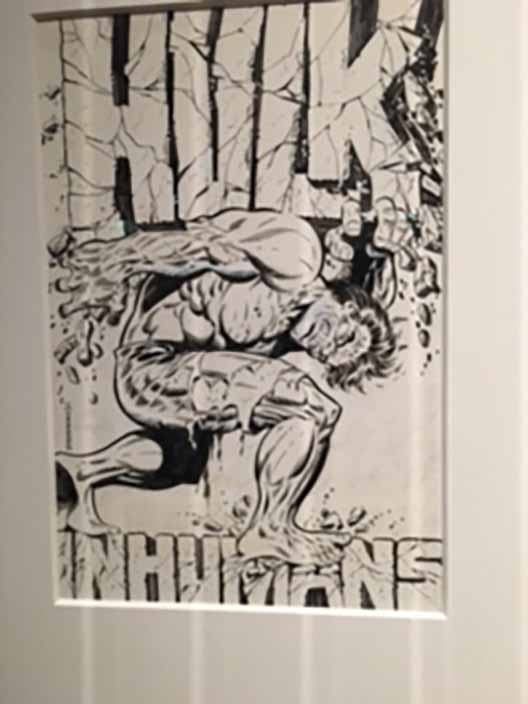

This exhibit expertly balances history with awe and fandom. The comics and pages on display, all in various stages of production, are often rare, in addition to being striking and fascinating in their own right.

The costumes and other props and artifacts from the recent slew of Marvel movies include the Tesseract, for example, and Loki’s helmet. My kids especially loved seeing just how much shorter some of the actors were “in person” than they seemed on screen.

If you’re strapped for cash, try offsetting the high cost of the Marvel exhibit by going to the MCA on a Tuesday, free museum day in Chicago.

If I still haven’t convinced you that these exhibits are worth the trip—there are plenty of comics to read online, after all—I’ll let Chris Ware give it a try. “If you look at a painting and don’t understand it, you’re likely to blame yourself for not being smart enough,” he digresses in one of his Cultural Center show tags. “But if you read a comic strip and don’t understand it, you just figure the cartoonist is an idiot. Cartoonists are used to being thought of as idiots. They don’t want to fool you or lie to you. Still, they are also real artists, and they work extremely hard. They make art you don’t look at, but look through. And like the city where it found its largest toehold, their best work is messy, real, and sometimes even beautiful.”

Having lived in Chicago when both Lynda Barry and Chris Ware were publishing new work in free weeklies like the Chicago Reader and New City, I would also argue that these exhibits couldn’t have happened anywhere else. The city’s heavy dose of cold, clouds, and wind as well as intellectual camaraderie seem to breed a grumpy yet hopeful sensibility best conveyed in comics, a format capable of the narrative equivalent of a sly wink at the reader when a character says one thing, and readers see something that complicates or undermines that statement.

Couple that with Chicago’s DIY sensibility, and you’ve got something truly special. As Christopher Borrelli puts it in his review of the Cultural Center and MCA exhibits, “The longer you hang out here, the more you recognize a cycle of innovation, homage and respect, rarely flowing from the top down.”

Don’t miss your chance to look—to really look at, not through—these powerhouse exhibits in the only city that could have birthed them.