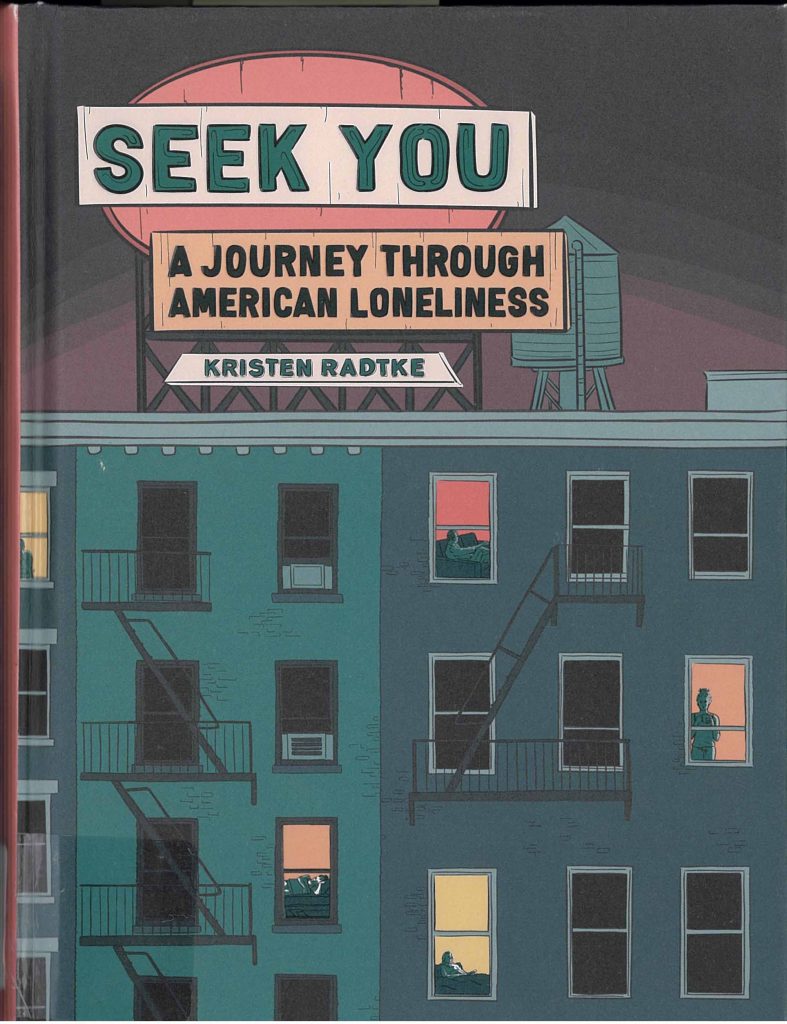

“Seek You: A Journey Through American Loneliness.” Written and illustrated by Kristen Radtke. Pantheon, $30. July 2021. 352 pp. Adult.

Disclosure: I received a free review copy of this book from Pantheon.

Content warning: Many readers have found the descriptions and illustrations of the primate research of Harry Harlow disturbing. Also, if you or someone you know is contemplating suicide, please contact the national suicide prevention hotline at 800-273-8255.

Thanks to Fables Books, 215 South Main Street in downtown Goshen, Indiana, for providing Commons Comics with books to review.

Check Fables out online at www.fablesbooks.com, order over the phone at 574-534-1984, or email them at fablesbooks@gmail.com.

“Loneliness is an emergency,” writes Kristen Radtke in a 2021 New York Times Book Review article. Radtke’s statement isn’t off the cuff. She’s been researching loneliness for her newest graphic narrative, “Seek You” since 2016, when she became disturbed and intrigued by the storm of isolation and paranoia swirling around the ugly presidential election year. The fear and suspicion that she was feeling as well as seeing around her, she discovered, were predictable side effects of a divided culture.

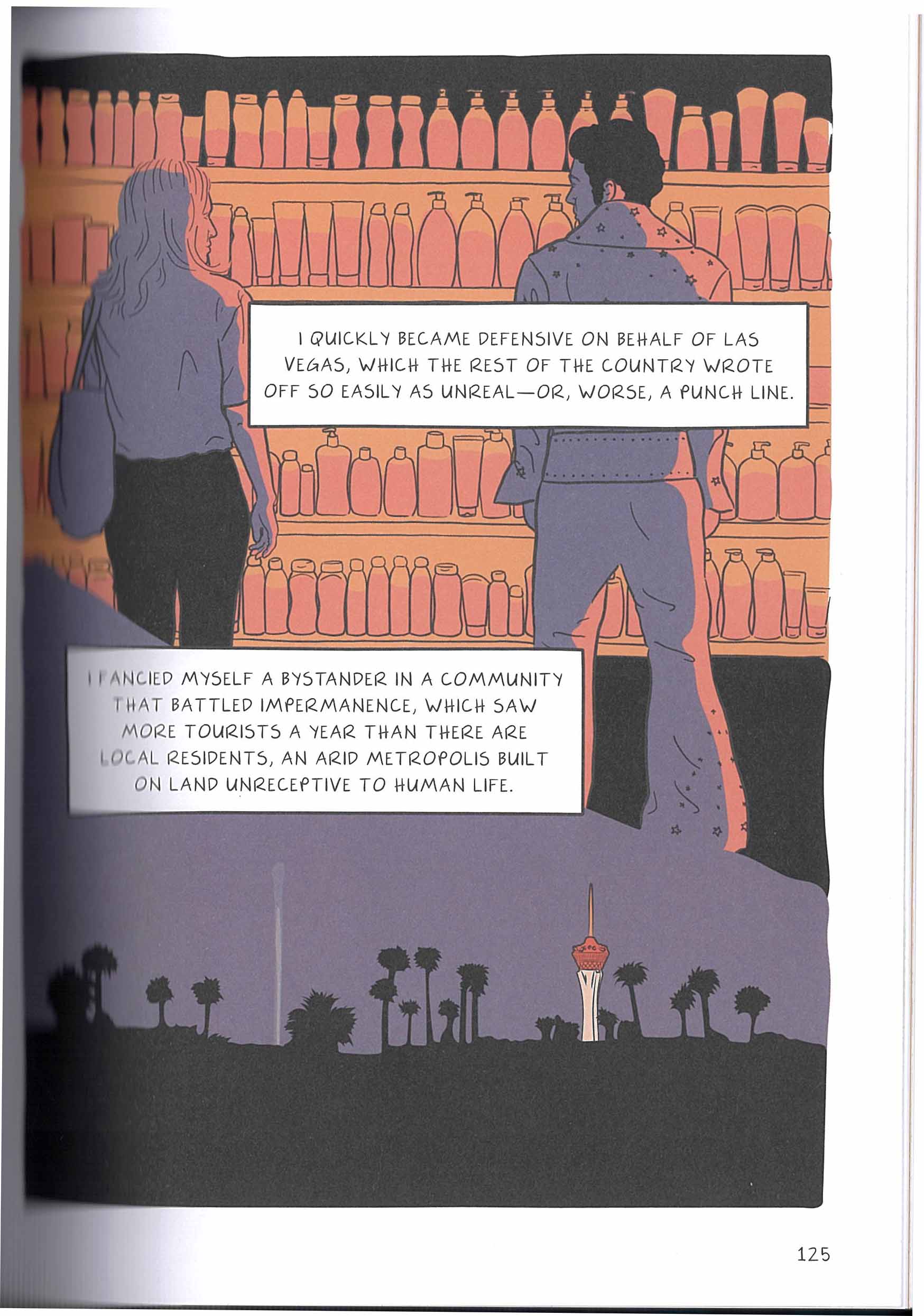

As she split her time between New York and Las Vegas, where she served as Art Director and Publisher for “The Believer” magazine, she began to notice Vegas’s distinct flavor of alienation, and the ways that it might serve as a microcosm of a form of isolation distinct to the U.S.:

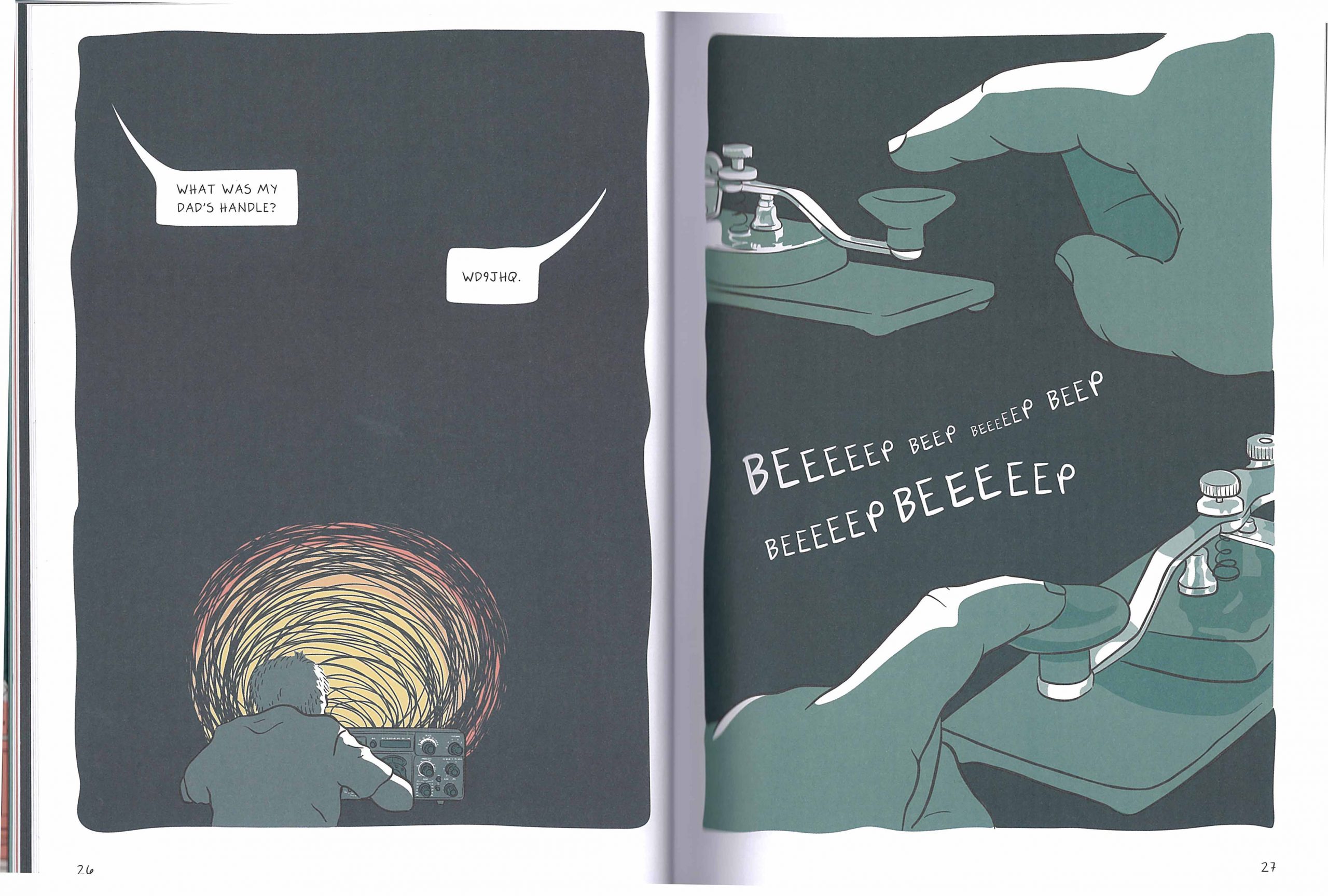

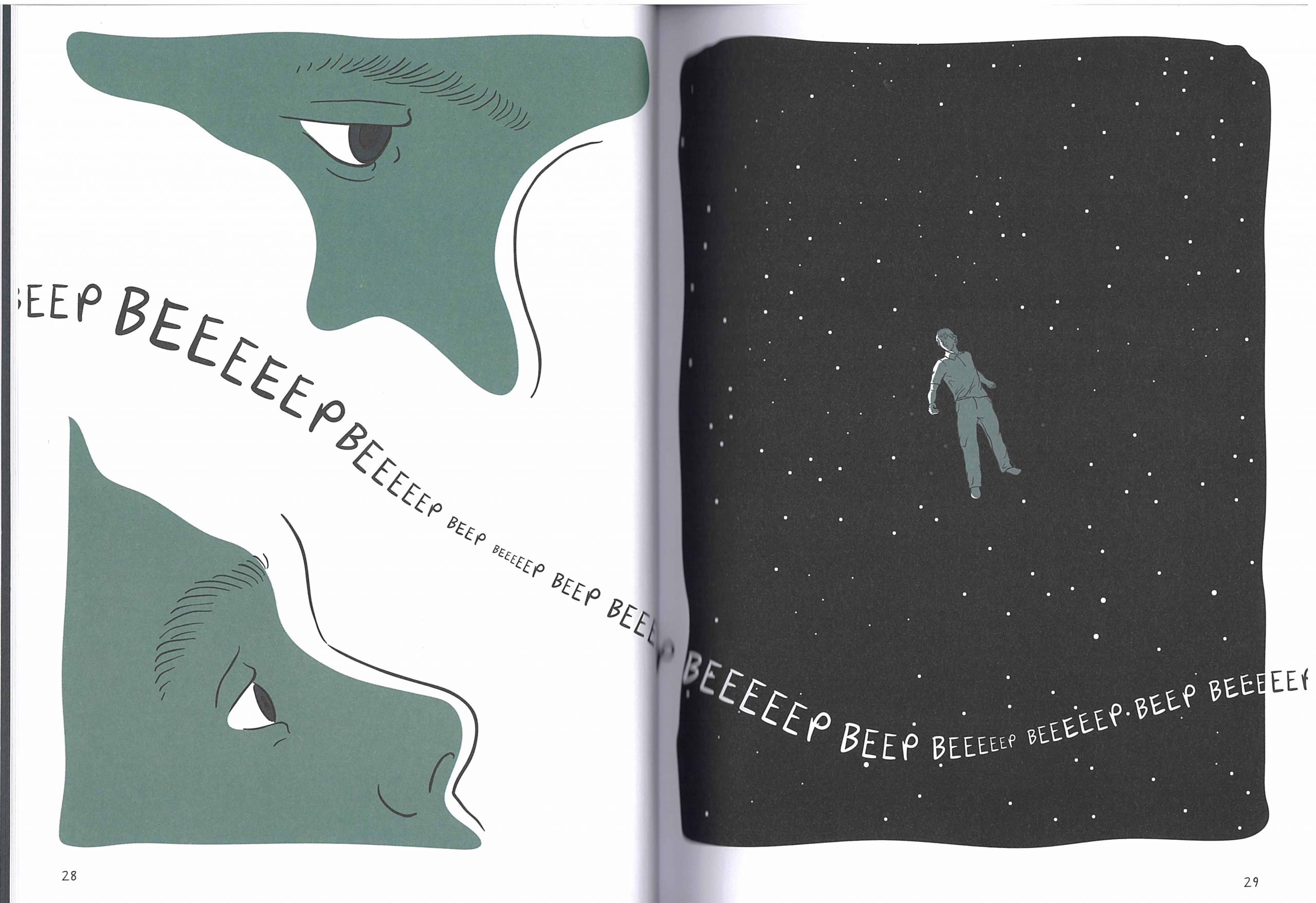

Clearly, this is not the first book on the topic of loneliness in the U.S. Radtke cites many well-known precursors, such as Sherry Turkle’s “Alone Together” and Robert Putnam’s “Bowling Alone.” This is, however, the first book on this topic in graphic narrative form, and it showcases the power and brilliance of the medium for delving into complex topics fueled by emotional undercurrents. While Radtke’s research might sound better suited for a dissertation or scholarly monograph than a graphic narrative, this book proves that this format is not only effective, but ideal. See, for example, this dreamy yet arresting sequence, which provides context for the book’s title:

As an adult, Radtke discovered during a long, late-night conversation with her uncle, that her quiet, strict, and generally feared father had, in his youth, spent long nights making “CQ calls” on his ham radio. The “Seek You” of the book’s title is a reference to the callout “CQ,” used by amateur radio operators to reach out to their peers. The signal serves no direct purpose, except, as Radtke puts it, as “an attempt to make a connection across a wavelength with someone you’ve never met.”

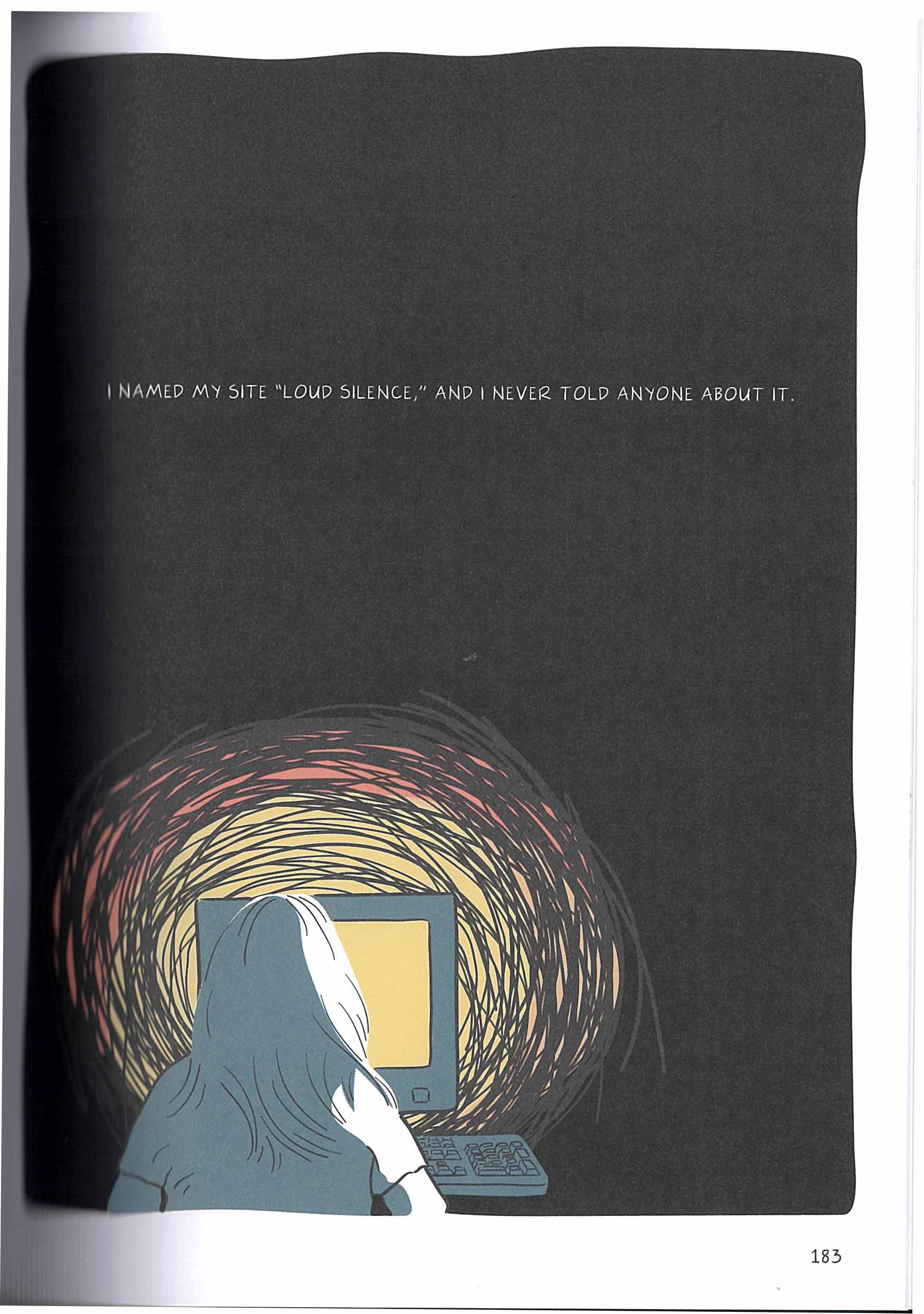

If Radtke’s stoic and seemingly self-sufficient father spent countless secret hours in his youth isolated but looking for connection, then how many of our seemingly distant fellow humans yearn for the same? She admits later in the book—in a neat visual echo for those paying attention—that as a teen, she was more similar to her father than she knew at the time. In the early days of the Web, she created and obsessed over a personal page, reaching out to the wider world without telling any of the people around her, even those under her same roof:

Radtke’s exploration is wide-ranging and loosely organized. Her chapter titles—“Listen,” “Watch,” “Click,” “Touch,” then “Listen” again—give her the leeway to explore less obvious historical markers on the way to our current state of isolation, which include laugh tracks, destructive pseudoscientific trends in mothering, Casey Kasem’s long-distance radio dedications, and John Wayne and Sandra Bullock movies featuring loner characters.

Radtke also asks whether and how much things have really changed. “[W]hen my father sat before his radio transistor in the ‘60s, was he any less lonely than I was, twenty-five years later,” asks Radtke, “waiting for the grinding of a dial-up modem to grant me access to a network of strangers?”

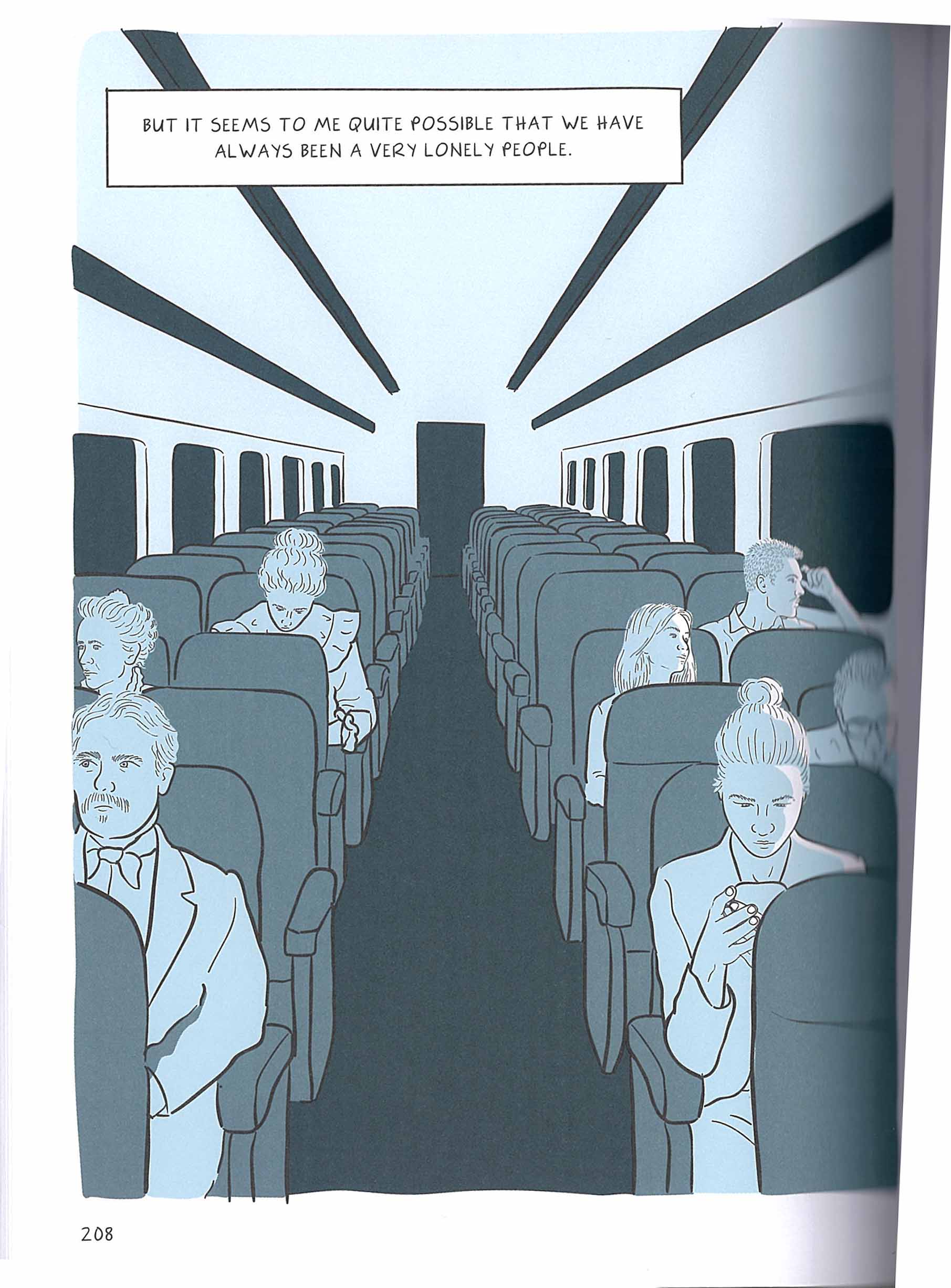

Images like this one ask a similar question, but in a way that only graphic narratives can. Note the center aisle’s 150-year wrinkle in time:

This is a book of questions more than answers, of fascinating speculation, as well as hopeful yearning. Radtke is an observer and philosopher, not a psychologist or sociologist. She writes graphic narratives and designs beautiful magazines (currently for “The Verge”). So while this book doesn’t try to provide definitive solutions to our nation’s problems, it does serve as an important check-in with ourselves.

As Radtke explained in an interview for “Hazlitt,” “I’m not saying there’s something wrong with wanting to live in the woods (there’s not), but I think that when we start to prioritize the self over the community—which I think we consistently do in America, and I think we saw this in the divides that arose during COVID—it starts to get very dangerous.”

Radtke helps highlight the fact that we’ve always been in charge of our own loneliness or connection, though we’ve always looked to new tools and technology to save us from it. Perhaps, she suggests, it’s time to look to each other, as well as ourselves. As she stated quite simply in an interview for National Public Radio, “I hope we remember that we need each other.”

Excellent write up!

Thank you! Thanks so much for reading–I really appreciate the feedback.