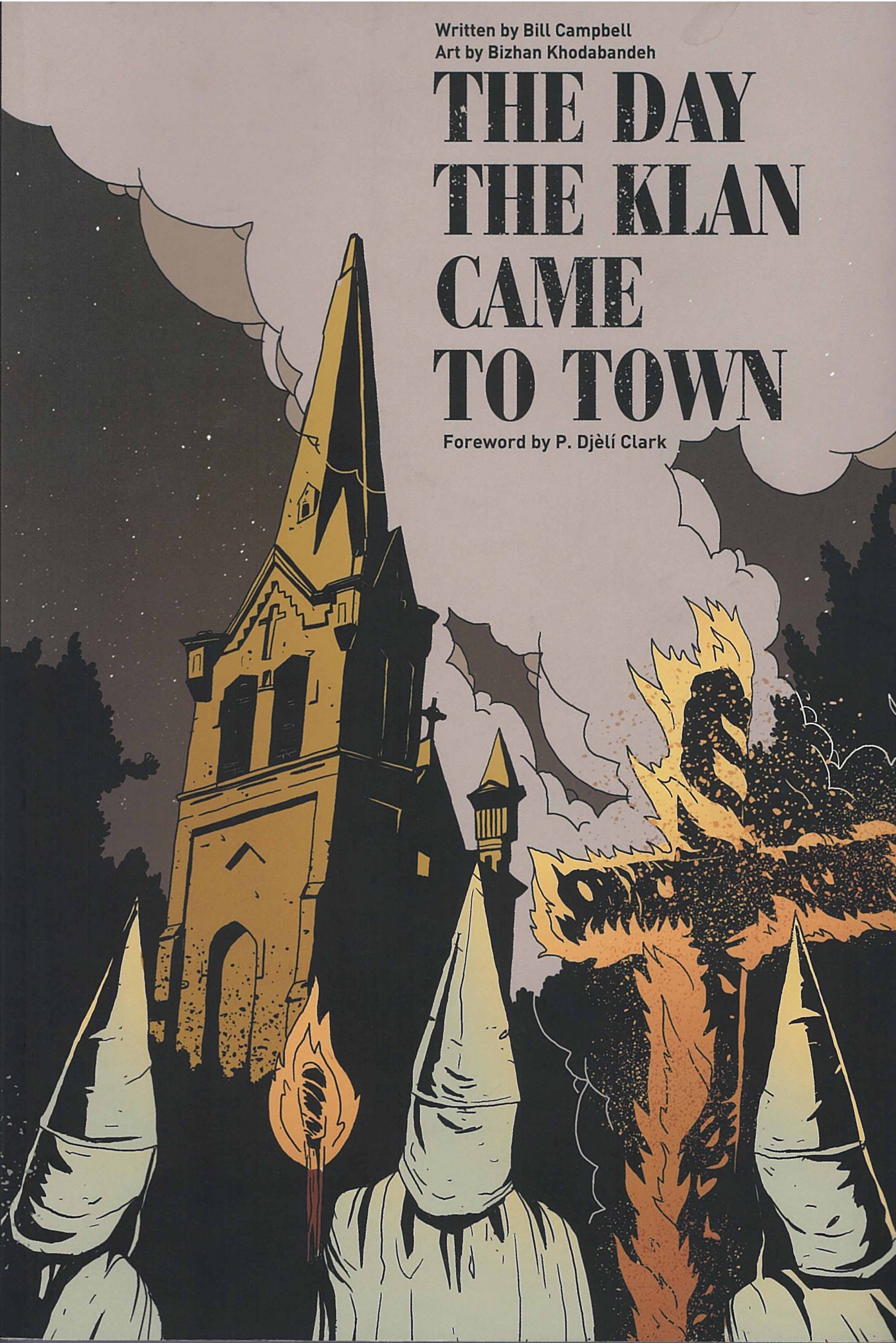

“The Day the Klan Came to Town.” Written by Bill Campbell, illustrated by Bizhan Khodabandeh. PM Press, $15.95. August 2021. 128 pp. Teen to adult. (My 9- and 12-year-olds loved it, but be aware that the book includes some violent and disturbing images.)

Disclosure: I received a free review copy of this book, and contributed to its Kickstarter campaign.

Thanks to Fables Books, 215 South Main Street in downtown Goshen, Indiana, for providing Commons Comics with books to review.

Check Fables out online at www.fablesbooks.com, order over the phone at 574-534-1984, or email at fablesbooks@gmail.com.

“I’m not a big fan of writing heroic tales,” claims author and publisher Bill Campbell in a recent interview for Fanbase Press. This statement might sound odd coming from the author of “The Day the Klan Came to Town,” a fictionalized account of a historic day in Carnegie, Pennsylvania, in the early 1920s. The mixed immigrant neighborhood of this small town outside of Pittsburgh banded together to resist and expel a violent Ku Klux Klan rally. If these scrappy townspeople aren’t heroic, then who is?

Campbell adheres to the more traditional sense of the term “heroic,” however. What he rejects aren’t stories about heroes, per se, but stories about oversimplified, unrealistically independent heroes, who triumph by means of their own sheer will and determination. While Campbell’s book does follow a main protagonist, Sicilian immigrant Primo Salerno, Campbell and his illustrator, Bizhan Khodabandeh, who works under the name Mended Arrow, make it clear that the story of Carnegie in in August 1923 is a story of collective, not individual, resistance, as well as a story that refuses narratives of victimization:

Campbell was initially inspired to retell this largely forgotten history not only because he grew up in Carnegie, but also because he didn’t hear this story until very recently. The silence surrounding the event posed a mystery. Wasn’t this the type of story that a town would tell and retell, maybe even dedicate a statue to? Why was this event not woven into the lore of his hometown? Why did he first hear about it in his fifties, instead of when he was a kid?

Like all historical questions worth asking, the answer was complicated. The basic facts: on August 25, 1923, between 10,000 and 30,000 Klan members showed up in Carnegie to rally on what they and some sympathetic local officials had deemed “Karnegie Day.” This was a high point of immigration in the US, which also meant a high point of backlash against immigrants. Support for the Klan was growing, and the track record of their demonstrations was violent. The group gathered on the edge of town, then set off toward an immigrant, mostly Catholic section of the city.

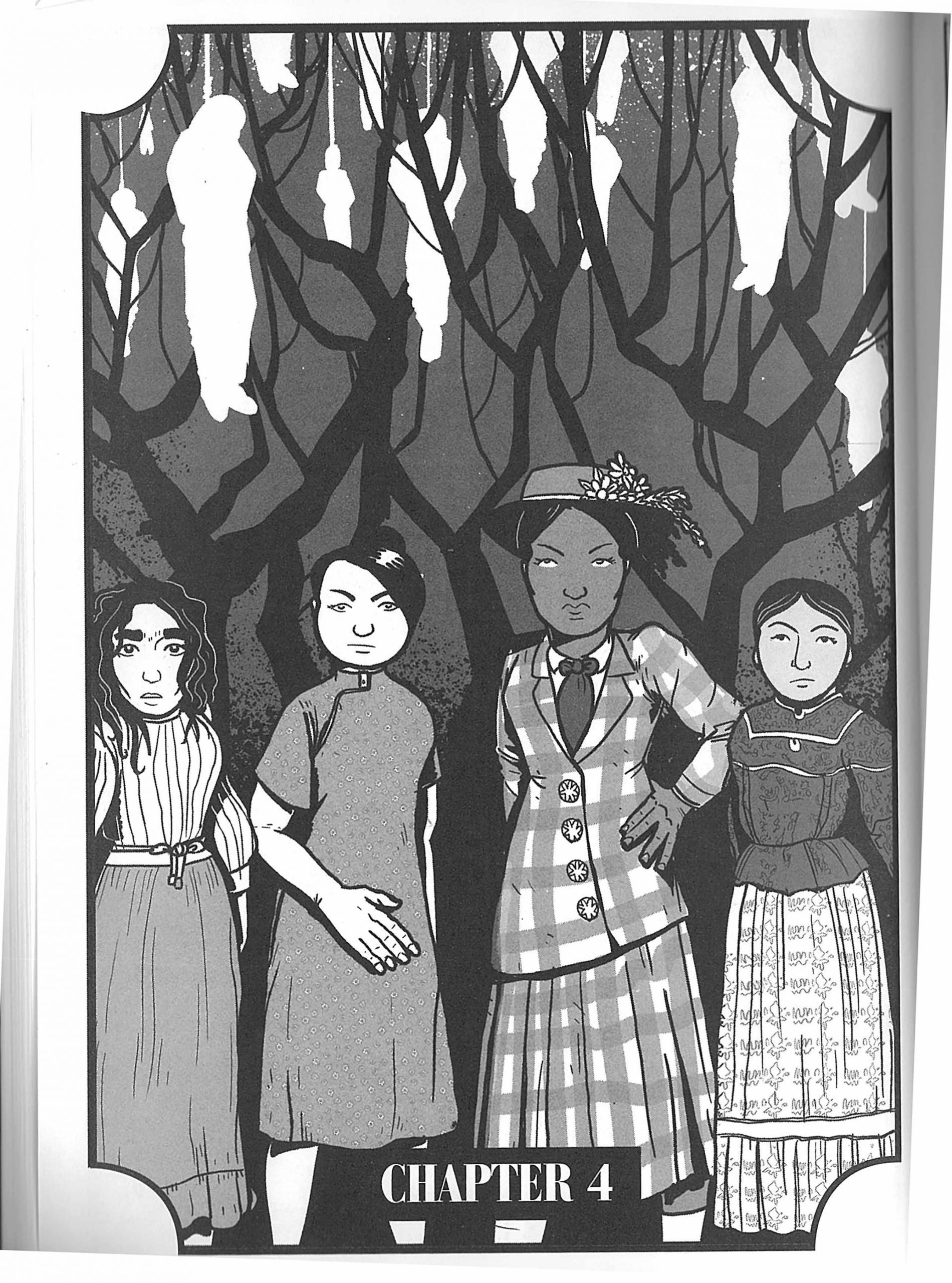

Who lived in the neighborhood they were targeting? Campbell looked to census records to find out, but was met with only the vague phrase “Irish and other.” Further research eventually filled in a likely profile of that “other.” As he told “Smashpages,” “This was the Irish part of town. But looking at pictures and census data, I know a lot of black people lived in ‘Irish town.’ I also knew that there was a German Catholic Church in Irish town.” Campbell’s research further suggested a range of Eastern and Southern European immigrants, especially Sicilians, like his protagonist Primo Salerno.

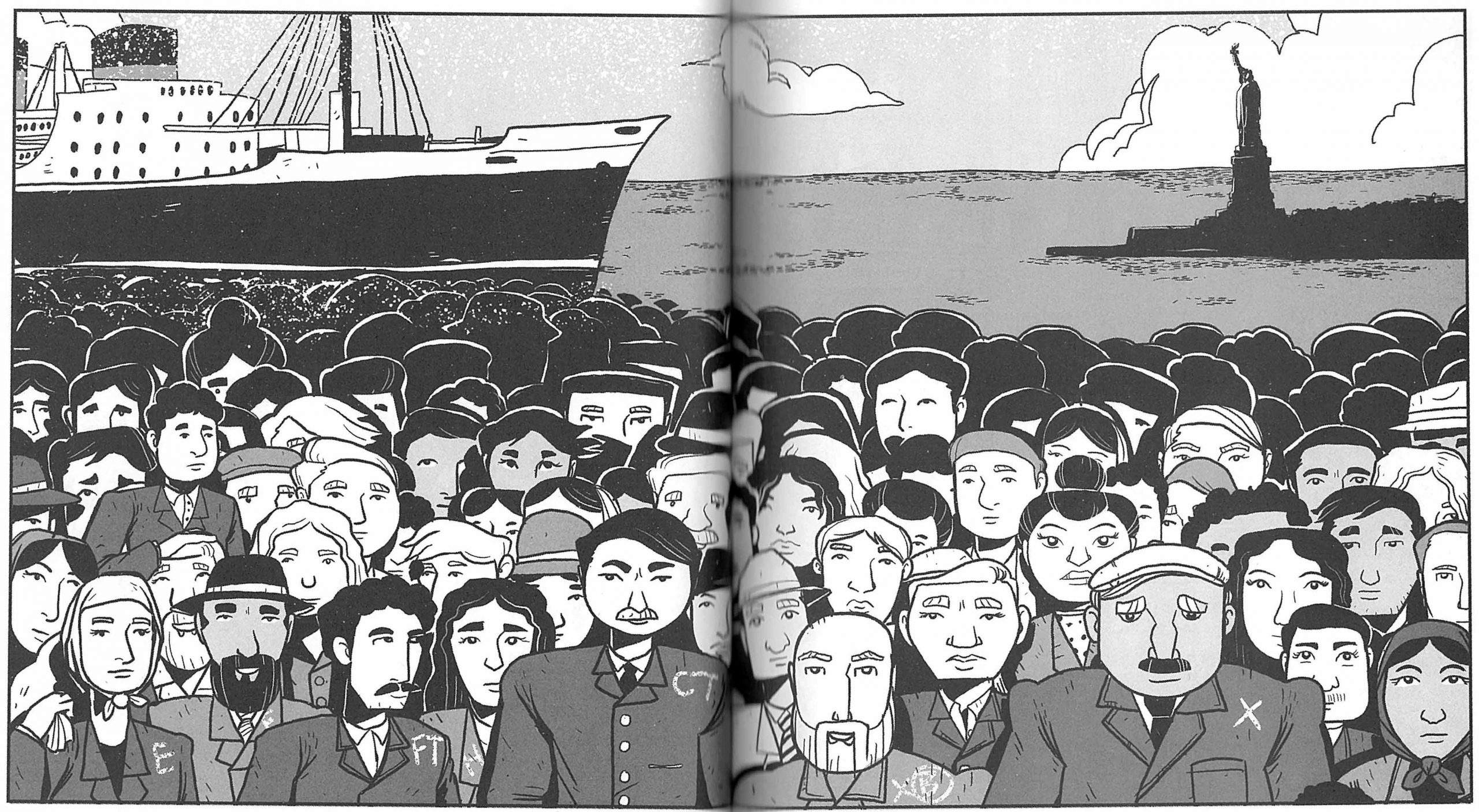

Khodabandeh highlights that spectrum of backgrounds in this image of Salerno, his friends, and a host of other new arrivals to the US in this era of peak immigration:

One of Salerno’s shipmates explains that the letters chalked onto their coats are code for diseases and other “liabilities” (like pregnancy and purported mental deficiency) determined during intake screenings. “You Italians call this place ‘the island of tears,” says his friend. “Half of these people will get right back on that boat. They need us, but they do not welcome us.”

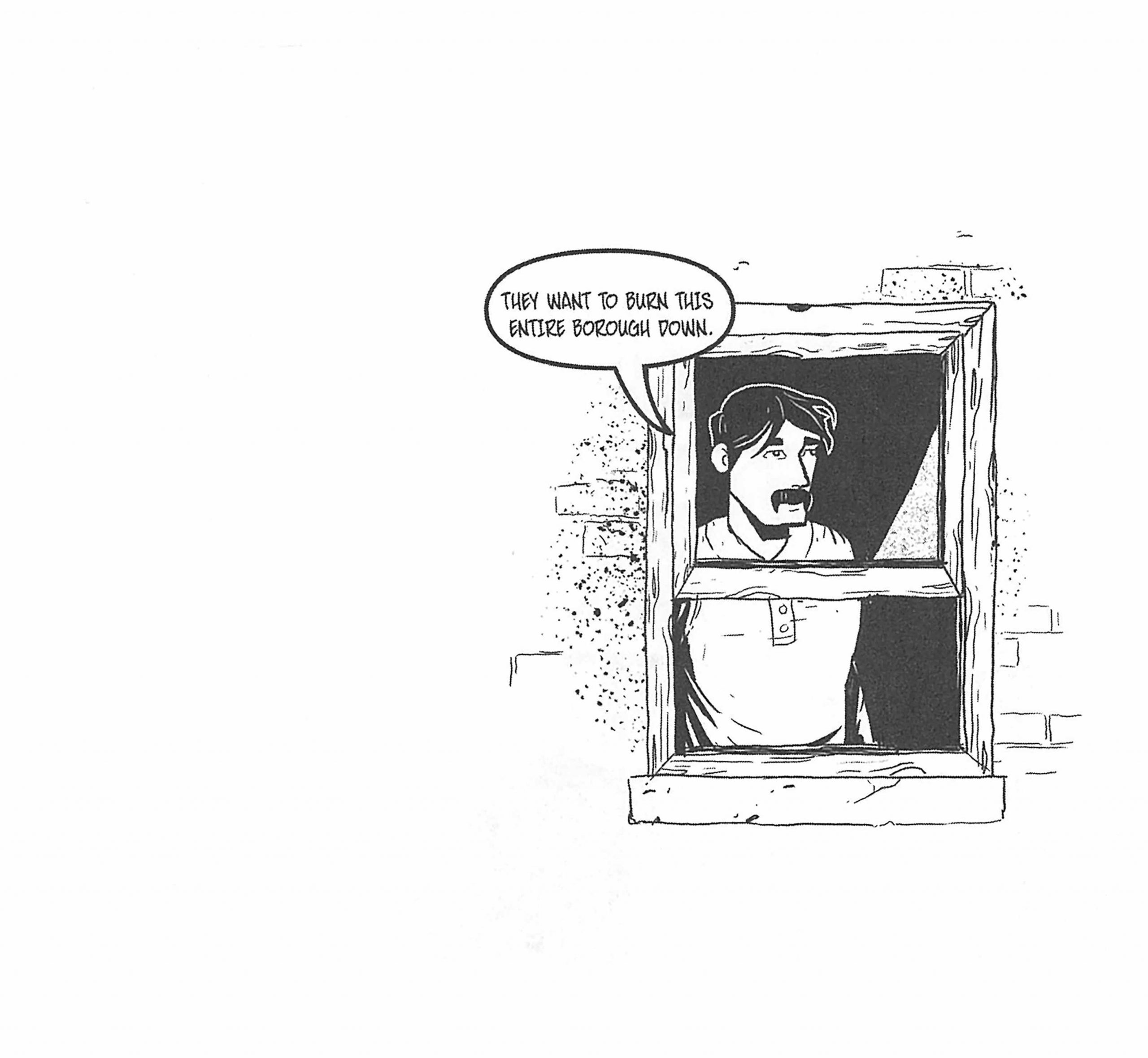

Through narrative flashbacks, readers learn that Salerno was born Cabbriele Parisi, but to escape persecution and military conscription, he takes on his new name and identity before setting sail for the US. When met with further injustice and persecution in his new country, Salerno realizes that he can’t keep trying to fight back alone.

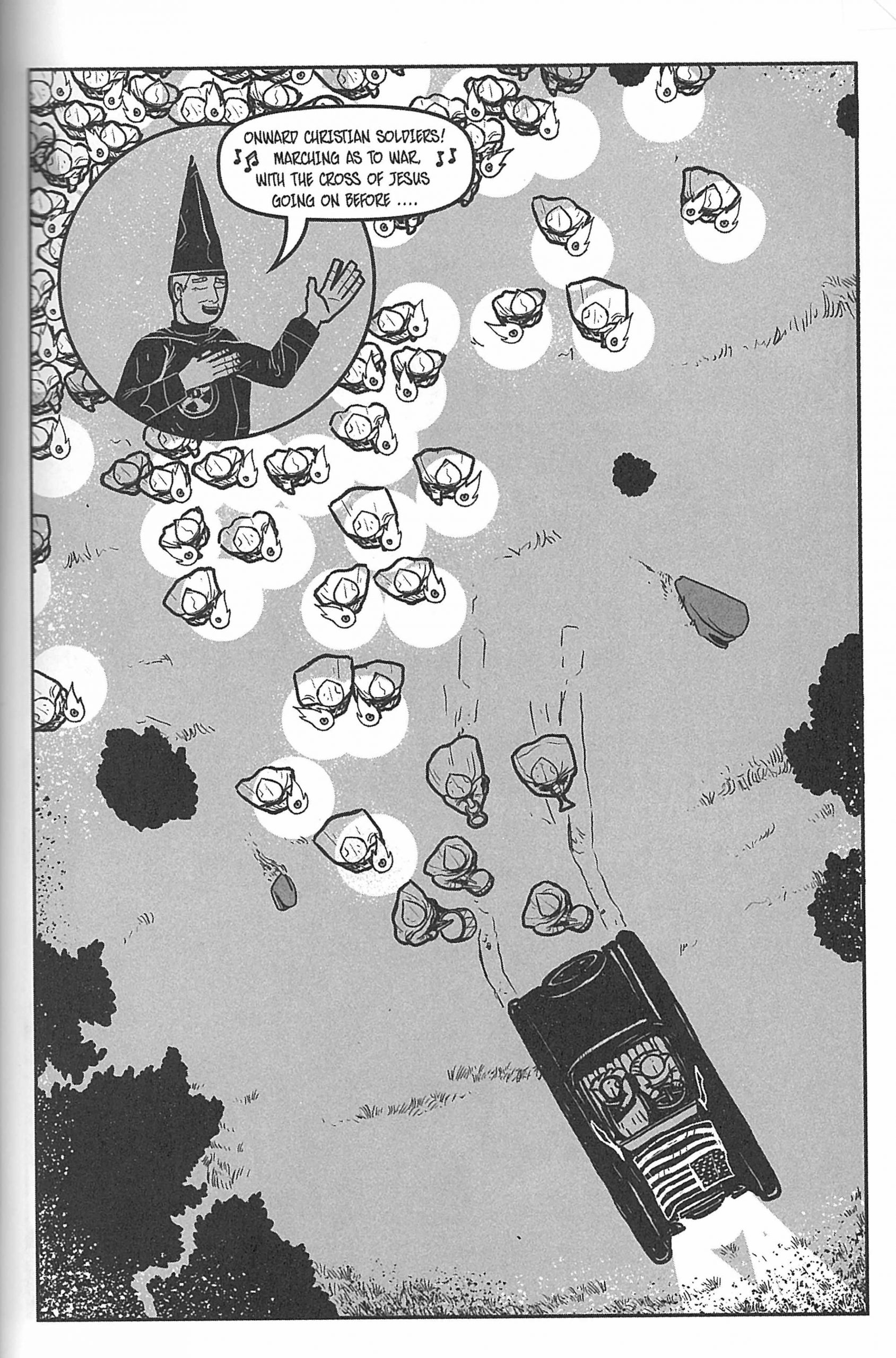

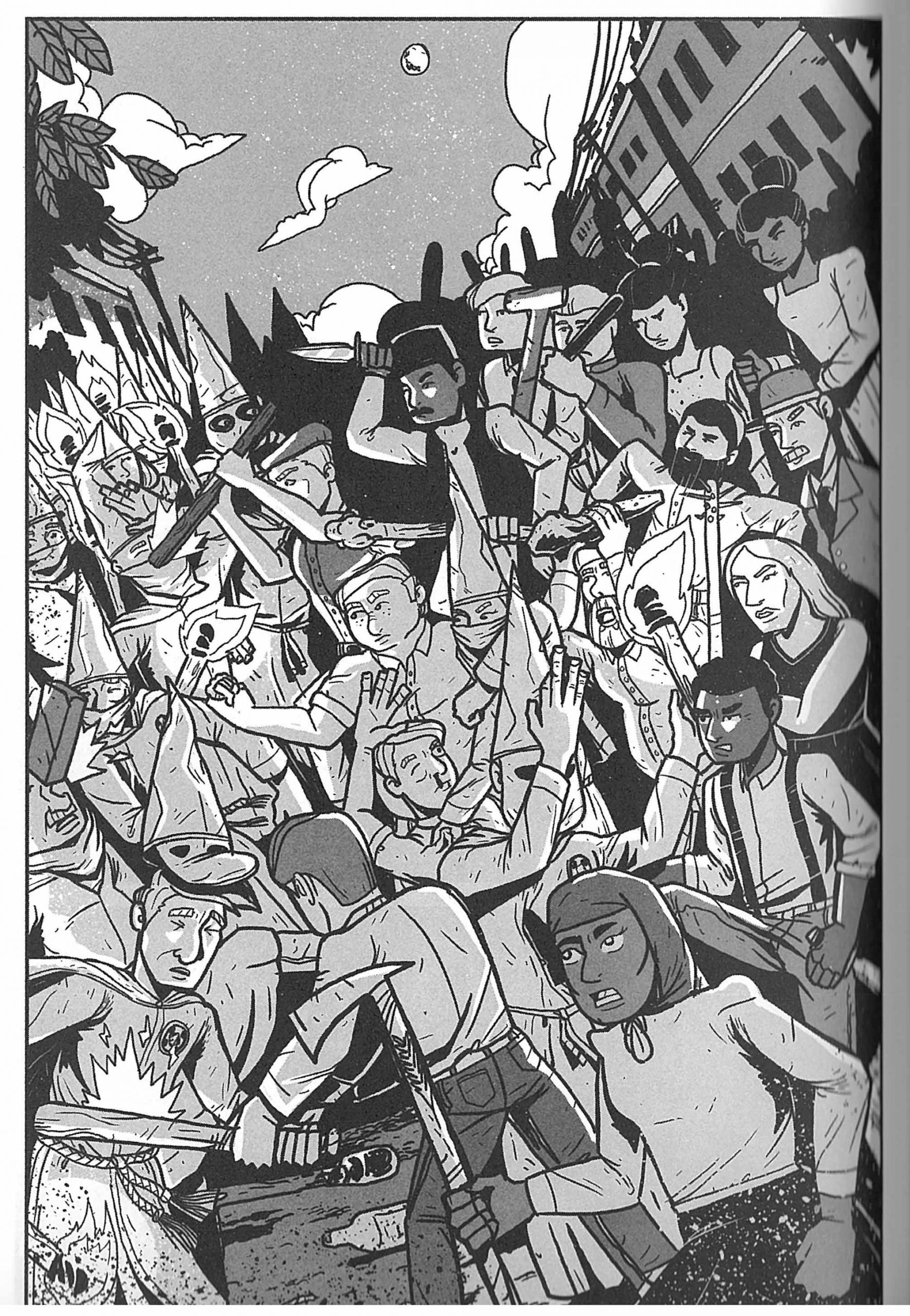

Images like this one, emerging out of whitespace, recall the transitional illustrations of Nate Powell in John Lewis’s “March” trilogy. Yet Khodabandeh has a definitive style of his own: his most striking pages mash up the bold contrast and flat perspective of European woodcut artists like Frans Masereel with the collective force of canvases like Picasso’s “Guernica.” While the abstract and sprawling style of “Guernica” might seem a far cry from comic book art, it carries a similarly dynamic representation of the chaos of violence against the innocent:

Despite this book’s visual echoes of Lewis’s “March” trilogy, however, it refuses a strictly nonviolent response to injustice—and for good reason. The inhabitants of Carnegie, faced with the need for immediate self-defense, were not given the time to dig in for long-term change. This neighborhood lacked not only the resources to build a nonviolent response, but even, quite literally, a common language. As Khodabandeh notes in an interview for Small Press Expo (SPX), “this is an instance where they are proactively stopping and driving out these horrible people from their space, and doing so successfully,” using, as Campbell told “The Comics Journal,” whatever they could grab: “people all around town were collecting coal, collecting fencing, and ripping cobblestones out of the street to defend themselves.”

As an article in “The Guardian” recounts, when Picasso lived in Nazi-occupied Paris during World War II, he had already completed “Guernica,” painted in response to a 1937 Nazi bombing of the small Basque Country town in Spain after which the masterpiece was named. A Nazi officer who raided Picasso’s apartment pointed at a photograph of the work and asked, “Did you do that?” Picasso’s response—“No, you did”—might be apocryphal, but remains instructive. Campbell and Khodabandeh’s work likewise shifts the lens of history’s camera to interrogate the perpetrators, rather than rob agency from the targets of their attack.

In interviews and panel discussions, Campbell repeatedly resists sentimentalization of his story. “These people got together because they were desperate,” he states in the “Comics Journal” interview. Given how factionalized the US still is, “obviously lessons weren’t learned,” he adds, but “we can learn lessons from this if we choose to.” As he reminds readers in his afterword, Primo’s story “is a story not unlike what many people experience today in their searches for a better life. I feel like it’s a story worth telling over and over until people no longer choose to forget what others go through.”