“Shubeik Lubeik” Written and illustrated by Deena Mohamed. Pantheon. $35.00. English translation January 2023, 528 pages. Youth to adult.

Thanks to Fables Books, 215 South Main Street in downtown Goshen, Indiana, for providing Commons Comics with books to review.

Check Fables out online at www.fablesbooks.com, order over the phone at 574-534-1984, or email them at fablesbooks@gmail.com.

NOTE: I received a free review copy of this book from Pantheon.

Egyptian comics artist Deena Mohamed posted her first webcomic in a 4 a.m. rage, when she was only eighteen. She had been up late fuming at a misogynist article, “Ten Things to Look for in a Muslim Wife.” It was far from her first encounter with such content, but this time she hit a breaking point—fortunately for her fans, a productive breaking point. She channeled her fury into the creation of Qahera, a Muslim Egyptian superhero who not only fights back against such rhetoric, but uses her powers to battle suffering and injustice wherever she encounters it:

Qahera went viral—it touched a nerve with women globally—and Mohamed continues the webcomic today. She next set her aspiration to print. As she explained on the podcast “Egyptian Streets,” she wanted her fans to be able to find her work in a bookstore. “Shubeik Lubeik,” which won the Cairo Comics Festival in 2017, was initially published in three installments in Egypt, and the collected English translation—which Mohamed undertook herself—is now available on Pantheon. Mohamed’s translation also maintains the Arabic right-to-left reading orientation, perhaps most familiar in the West to fans of manga comics.

Shubeik lubeik is Arabic for “your wish is my command,” a phrase familiar to many readers from stories like “Aladdin.” Mohamed subverts the Westernized mythical figure of the “genie,” deepening its Middle Eastern roots as “djinn.” That might sound like a goal with the potential to be preachy and heavy handed, but Mohamed is such an expert storyteller, you’ll have a hard time putting this book down.

In Mohamed’s magical realist tale, wishes are for sale: mined, then bottled or canned. As with any commodity, the quality and effectiveness of each wish varies, depending on how much you can pay. First-class wishes are housed in elegant glass bottles, and upon release, their Arabic script translates into a politely worded greeting, such as, “Your servant is at your service”:

while third-class wishes come out of soda cans or other cheap vessels, and issue gruff queries:

In Mohamed’s interpretation, djinn are only lightly personified: they don’t spin into high-speed standup routines like Robin Williams’s voiced genie or glare imposingly like Rex Ingram in “The Thief of Baghdad.” As she explained in an interview with “Screenspeck,” “since ‘wishes’ are most famous in orientalist or folklore traditions, I wanted to make sure the story felt like an authentic Egyptian story of magical realism and not like some kind of alienating ‘Aladdin’ remake.”

The low-budget wishes do, however, like to play jokes, which has filled the more distressed neighborhoods in Mohamed’s version of Cairo with bizarre artifacts like a luxury car stuck in a tree: wished-for, granted, but never to be driven. The trickster wishes can also lead to sinister outcomes, such as extra arms and other facial and bodily mutilations. These human casualties of the book’s fantastical wish economy wander through the story’s background scenes, sparking double takes for alert readers.

Mohamed makes it clear, however, that the problem isn’t the wishes themselves, as much as the system that extracts, exploits, and profits off of them, beginning with European colonial structures of exploitation. Third-class wishes, for example, are called delesseps, or “bad deals,” after French diplomat Ferdinand de Lesseps, who left Egyptians with the short end of the stick in his drive to develop the Suez Canal. In Mohamed’s story, the mantle of corruption clearly began with colonialism, but has been adopted by local bureaucracy in Cairo.

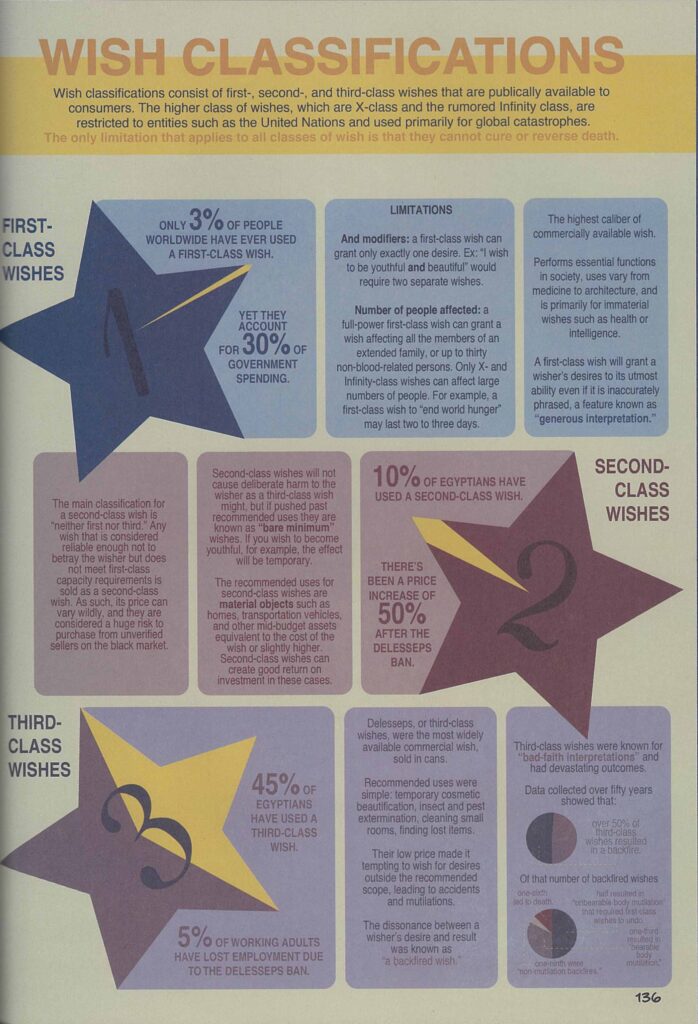

Interspersed between the three main storylines are rich and witty infographic parodies of oversimplified histories, in this case concerning wishes:

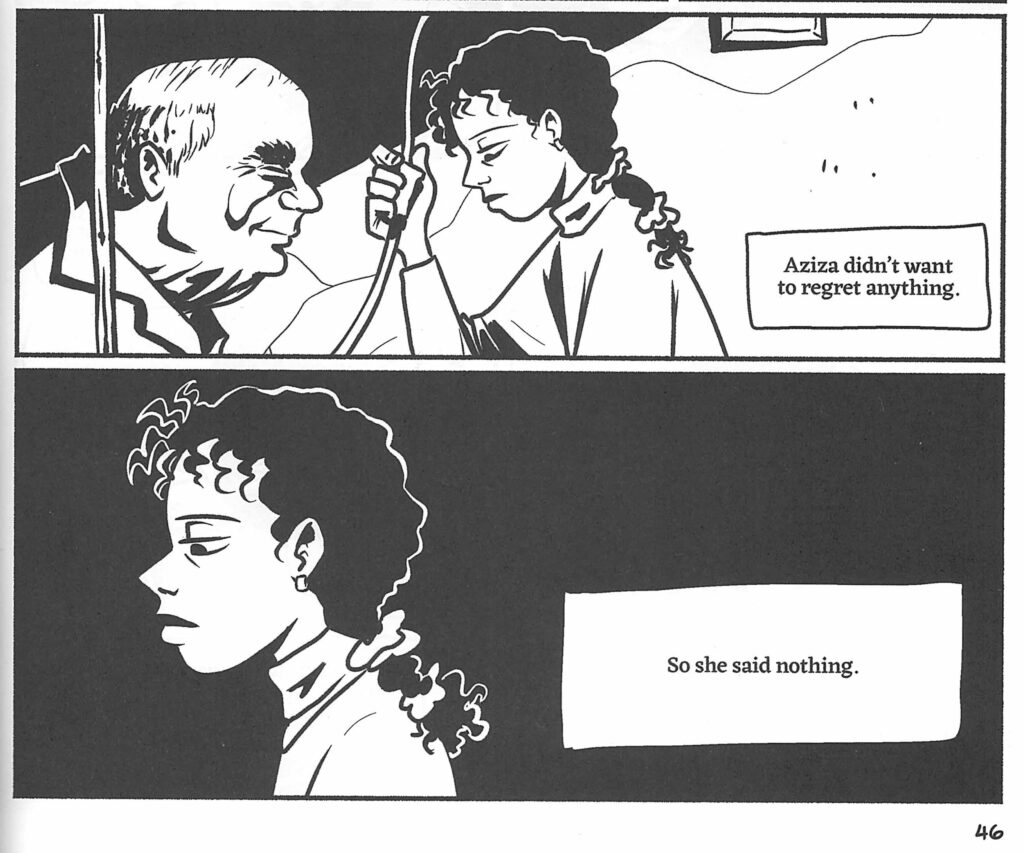

While the characters in the story are allowed only one wish each, readers are granted three storylines. The first follows Aziza, a woman who, in the face of a staggering number of life roadblocks, works hard to gain her wish, only to fall prey to the whims of local bureaucracy:

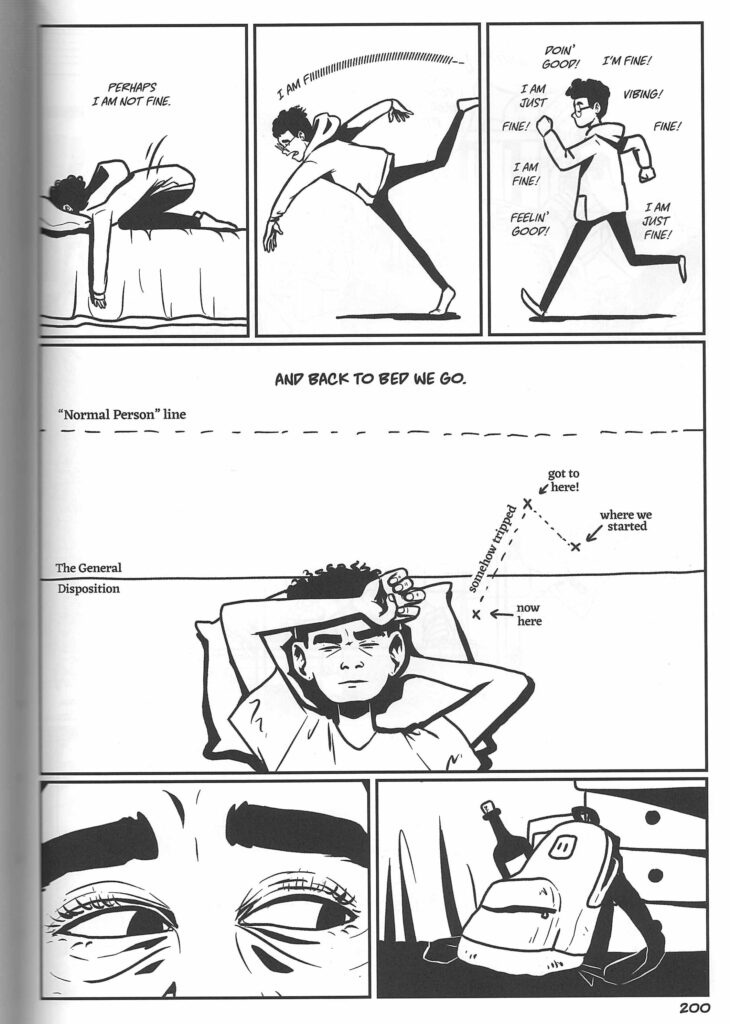

The second goes to Nour, a college student privileged into near paralysis. Although they can easily buy the wish, for most of their story, depression makes it near impossible for them to use it (remember to read from right to left):

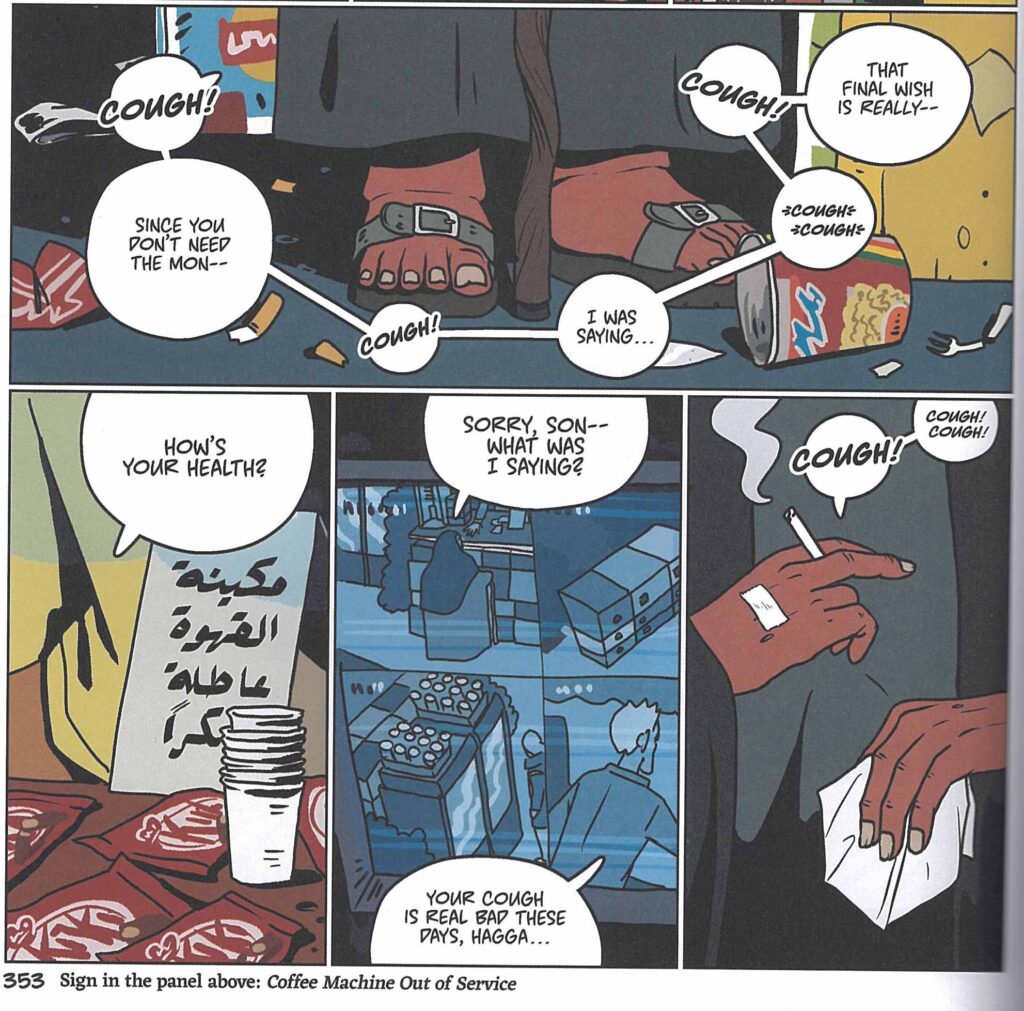

The third and final story follows Shokry, the owner of the kiosk where Aziza and Nour bought their wishes. Shokry believes that his Muslim faith allows him to sell the wishes, but not to use them himself. No spoilers, but he considers using his third unsold wish to help a longtime friend.

“I knew I couldn’t have a book about wishes without thinking about grief,” Mohamed told PEN America. Nour, of the middle storyline, is the only character who doesn’t lose someone they love, but Nour’s complicated grief stems from losing himself into depression—which Mohamed also portrays with graphs and charts that brilliantly merge humor and compassion. As she told Douglas Wolk in an interview for Kirkus, “Those were really fun for me. Part of representing depression was that I didn’t want it to be too depressing.”

Mohamed’s initial goal of publishing in print bumped her career up to another level: the print version drew the attention of the same literary agent who helped Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis gain worldwide recognition. Mohamed has been doing what she loves ever since, and has also been using her global success to help strengthen the comics community in Egypt. As she told “Egyptian Streets,” “Comics don’t make money in Egypt yet because we just don’t have a big industry. . . . It’s not really an easy or convenient career path. You just have to find your ways around it.”