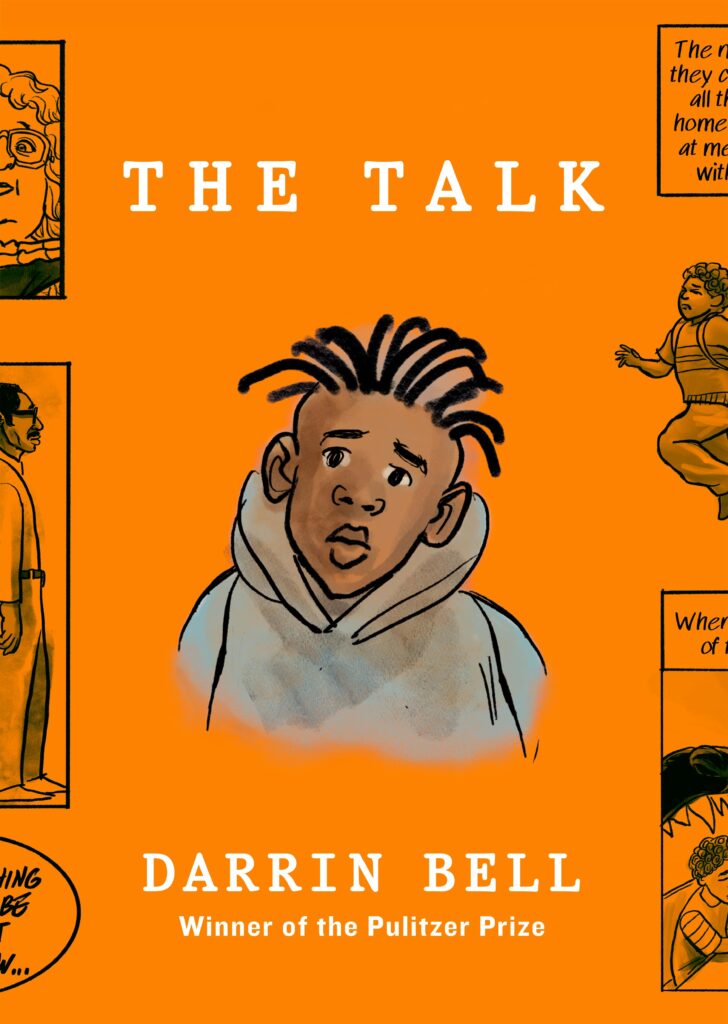

“The Talk.” Written and illustrated by Darrin Bell. Henry Holt. $29.99. June 2023. 352 pages. Teen to adult. (School Library Journal suggests Grade 10. My 7th and 9th graders enjoyed and learned a lot from it.)

Thanks to Fables Books, 215 South Main Street in downtown Goshen, Indiana, for providing Commons Comics with books to review.

Check Fables out online at www.fablesbooks.com, order over the phone at 574-534-1984, or email them at fablesbooks@gmail.com.

Thanks also to my colleague Cynthia Good Kauffman for passing her copy of this book on to me.

Before his 2023 graphic memoir “The Talk,” Pulitzer Prize-winner Darrin Bell was known as a political cartoonist more than a memoirist. “The Talk” earned him a new fanbase, as well as multiple best-of-the-year accolades, from “Publisher’s Weekly” to “Time.” The book was so successful, in fact, that Bell’s publisher wanted to extend its reach to another format. Documentary? Fictionalized film? Nope. The audiobook version of “The Talk” was released in August of 2024.

You’re probably thinking what I was thinking when I heard this news: “Audiobook from a comic? How does that even work?” Bell was skeptical, too, he told “Comics Beat,” “until I read the script.” Much like screenplay writers are hired to rework books for film, Macmillan hired a scriptwriter, who turned Bell’s story into, essentially, a radio play.

While audio and the visual medium of comics might sound incongruous, comics and radio plays have a longstanding history, especially in serial radio programs which, in the days before television became widespread, kept families up to date with characters like Dick Tracy, Little Orphan Annie, and a slew of action heroes from the Lone Ranger to Superman. In homage to this history, Gene Luen Yang translated in the opposite direction, resurrecting a radio play from the 1940s to create his 2020 comic “Superman Smashes the Klan.”

Format retreads are often fueled solely by publishers with dollar signs in their eyes. With the right people involved, however, a format translation can create a new way of seeing—and hearing—important stories that need to be in the world.

“The Talk,” without question, is a story that needs to be heard right now. In 2020, Bell was working on a different project for Macmillan, a graphic memoir family history. As he told “Kirkus Reviews,” however, “when the police murdered George Floyd and the summer of protest began,” his young son asked who Floyd was, and “The Talk” began to take shape in his head. ”I felt that this story needed to be told first.”

“The talk” referenced in the title is a difficult discussion between parents and their kids of color about the way they might be perceived in the outside world—the way many people, especially white people, police officers, and others in positions of power, might see them differently than they see white kids. This unequal perception can, of course, put kids’ lives at risk through no fault of their own.

Bell himself first heard “the talk” from his mother when he was six. He asked her why his water pistol was bright green and obviously fake, when his friends’ squirt guns looked more realistic. “Because, Son . . . that’s what’s going to keep you alive,” Bell’s mom responds in his retelling. She delivers the talk for a few panels, and—as might be expected from a six-year-old—he promptly ignores it. As Bell told WNYC’s Alison Stewart, “I knew everything, and [Mom] was old and out of touch. She was born in the ’40s when TV was in black and white. I didn’t think she had any wisdom to share with me in 1981.”

Untroubled, young Bell ventured out with his fun summer toy, imagining himself as Luke Skywalker:

Yet the Force did not protect Bell from exactly the danger that his mother had predicted: a cop who saw the color of Bell’s skin instead of the bright fluorescence of the toy—and pulled his gun on six-year-old Bell. Bell of course survived that encounter, but has never forgotten that he “could’ve ended up like Tamir Rice,” as he told “Comics Beat.”

Clearly this is a serious topic, and Bell treats it with the weight it deserves. As you can tell from the playful Star Wars page above, however, he doesn’t sacrifice joy, beauty, and complexity to get his point across. Using his chops as a political cartoonist, he can pack a punch in one or a handful of panels, as in this illustration to break any parent’s heart:

Yet with the space to stretch his talents into a full storyline, Bell also conjures multifaceted sequences like this one about his thought process before a dishonest and disloyal “friend” asks Bell to come with him while he shoplifts, then leaves Bell to take the blame:

As in the best memoirs, none of the main characters in “The Talk,” including Bell himself, are oversimplified. Bell repeatedly turns the critical lens back onto himself, and shares plenty of moments he isn’t proud of. In one vignette, for example, he explains how his job as a security guard in college helped him understand “the true allure of power” when he recognized that he wasn’t immune to its attractions:

Color is used sparingly in this book, but creates both focus—as with the bright green water pistol—and depth, like the chiaroscuro effect in the image above. The illustrations are a masterful combination of rich and nimble, as Bell continually shifts gears and perspective to hold his readers’ attention. Bell plays with contrast wherever he can. The glossy paper highlights the photorealistic depth in, for example, a dog’s wet black snout, but Bell counteracts the weight of that image almost immediately to encircle the snout with scribbled puffs of air that float between panels, connecting the frames visually as well as conceptually.

In the book’s acknowledgments, Bell thanks all the people who helped and held him up, as well as, “The cop, the security guard, the administrators, and the occasional random bigot who, rather than make me feel bad about myself, made it clear that bigotry is just chronic stupidity.” Whatever format you choose to “read” this book in, please read it, and pass it on to someone else.