“Kwändür.” Written and illustrated by Cole Pauls. $25.00. November 2022, 140 pages. All ages.

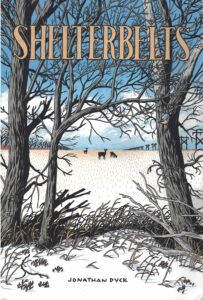

“Shelterbelts.” Written and illustrated by Jonathan Dyck. $20.00. May 2022, 224 pages. Teen to adult: Contains drug references.

Thanks to Fables Books, 215 South Main Street in downtown Goshen, Indiana, for providing Commons Comics with books to review.

Check Fables out online at www.fablesbooks.com, order over the phone at 574-534-1984, or email them at fablesbooks@gmail.com.

NOTE: I received a free review copy of Shelterbelts from Mennonite Quarterly Review. Portions of this review have been adapted from that one.

“I see publishing as an art form,” Andy Brown, founder of Conundrum Press, told “Broken Frontier” in late 2022. Valuing careful curation over profit has paid off for the press. Brown started Conundrum in 1996, but narrowed its mission and focus to literary graphic novels in 2010, catching the early edge of our current comics zeitgeist. Now based in Wolfville, Nova Scotia, Conundrum continues to steadily and quietly gain readers and recognition.

Conundrum also works to build comics community, and has instituted a fund—or “bursary,” in Canadianese—to publish mini-comics by emerging black and indigenous authors. Keep an eye out for example, for rising stars Talysha Bujold-Abu, Jazz Groden-Gilchrist, and Jordanna George, the first three recipients of this funding, which began in 2020.

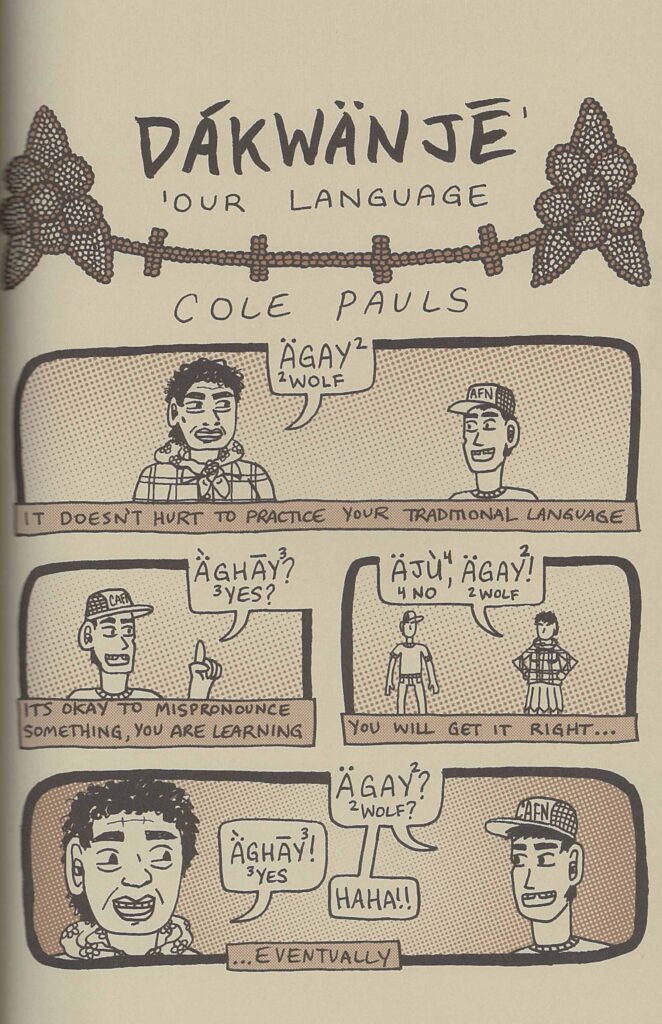

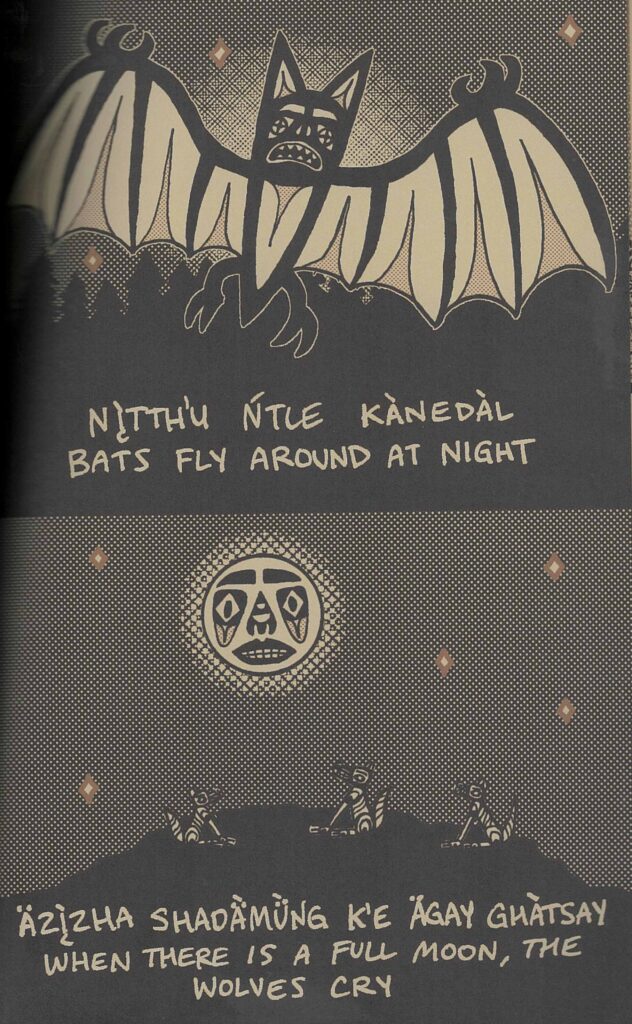

Conundrum was diversifying its library long before the summer of 2020, however. One indigenous author that Conundrum has been publishing since 2019 is Cole Pauls. The Canadian Broadcasting Company calls Pauls’ work “Indigenous Punk,” but he told an interviewer for “Discorder Magazine” that “Indigenous Futurism” might be more precise. For “Dakwäkāda Warriors,” the young adult sci-fi allegory that Pauls began in 2016 as individual zines, he worked with elders from his community to make the book bilingual, placing the Southern Tutchone language alongside English. (Pauls calls himself a Champagne and Aishihik Citizen and a Tahltan comics artist.) The words share the page with aliens and space lasers to create an allegory against forced assimilation.

“I want Indigenous youth to read my book and see themselves and their culture 1000 years from now. It’s the idea that we’re still here and we’ll be here in the future,’” Pauls told “Discorder.” As a kid, Pauls felt like he saw himself in books only on rare occasions. One of those books was “Alsek’s ABC Adventure,” written by fellow Yukon Territory author Chris Caldwell. As Pauls explained to High Country News, even though Caldwell wasn’t indigenous, “it blew me away that there was one children’s book about the Yukon, specifically the land that I was from. I was astonished by it. . . . I want the kids in my hometown to read [my] book and be like, ‘Wow, I have an identity.’”

Pauls brings a similar joy and enthusiasm, as well as striking design, to his most recent book, “Kwändur,” a collection of his zines and previously published shorts. Kwändur translates to “stories,” which serves as an all-encompassing term for these personal vignettes, which range from how-tos to indigenous legends, and also share intimate flashes of Pauls’ life with the indigenous side of his family. In this two-page spread, for example, from the story “Kwän”—which translates to fire, implying that that’s where stories are meant to be told—he sets up camp with his grandmother:

As Conundrum’s site notes, Pauls’ heritage lies with the Dene and Arctic peoples, yet as these stories explain, he too often finds himself defending his heritage. In the story that opens the collection, a classmate in a college art critique accuses him of “appropriating” indigenous designs. Honest stories like this help readers comprehend the frustrations of living in a body that doesn’t match society’s manufactured—and too-often destructive—stereotypes.

Difficult stories like this don’t cancel out the overarching joy of this collection, especially when Pauls lets readers into life with the Tahltan side of his family. Like “Dakwäkāda Warriors,” much of this book is bilingual, written in both English and Southern Tutchone. Pauls also infuses a healthy dose of cheerleading for language practice and preservation, encouraging Indigenous readers to speak their traditional languages even if they’re unsure or uncomfortable.

Haida visual and comics artist Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas, who, like Pauls, hails from the Pacific region, makes a strong claim that the bold designs from this region served as an early form of comics, their large geometric spaces with thick, dark outlines acting as panels. Elements of Pauls’ line work are similarly thick and dark, but carry an added edge of grunge, what Pauls calls his “pizza punk” aesthetic:

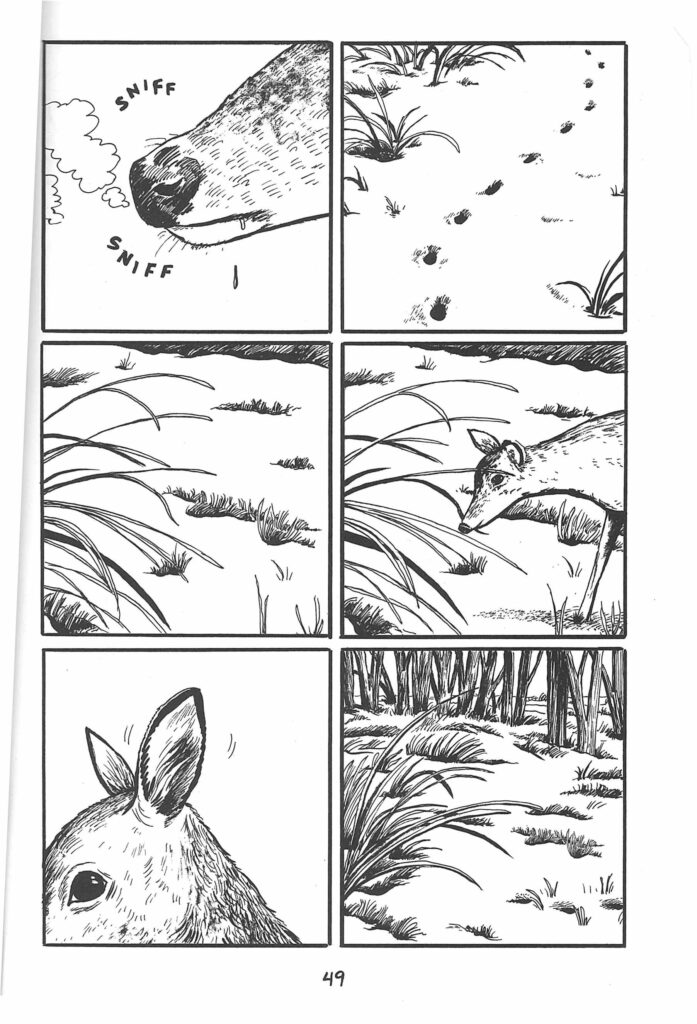

The style of Pauls’ fellow Conundrum author Jonathan Dyck differs drastically, but Pauls and Dyck share more similarities than readers might think. For one, in his fictional short story collection Shelterbelts, Dyck also saves visual time to pause and take in nature,

but much like in Pauls’ work, these moments of peace aren’t used to cover up or distract from injustice, but instead to present readers with the nuances of complex situations—conundrums, as it were. The many characters in Dyck’s interconnected short stories all weave in and out of each other’s crises in the rural Canadian town of Hespeler—which is fictional, but will ring true to anyone with experience living in small-town North America. These stories carry the open yet thoughtful endings required of a book called “Shelterbelts,” a word with a complicated history. Farming shelterbelts—grids of trees planted not only as windbreaks, but to build sustainable habitat—were created as early as 1880 in parts of Canada to protect the land and its settlers. Yet whom did they exclude, and whom do they continue to benefit, as well as to harm, especially when the land was acquired unfairly in the first place?

The conflict that opens the collection takes place at a small, progressive Mennonite church: two longtime members of the church leave because of the pastor’s outspoken support for his LGBTQ+ members, one of whom happens to be his daughter. A more conservative local megachurch is siphoning membership via a charismatic pastor who also has a bad habit of glossing over injustice. This is only the first of multiple conflicts in the book, as characters grapple with indigenous land rights, an impending pipeline project, and the tension between supporting veterans and encouraging peace.

In less expert hands, this book would thin to a political diatribe, but Dyck has instead built an engrossing exploration of the fraught intersection of history, conviction, and action. Critics so far agree that “Shelterbelts” reaches well beyond the stereotype of the rural Canadian community it represents: it has garnered a coveted starred review from “Publisher’s Weekly,” was excerpted in “The Comics Journal,” and is blurbed on its back cover by Seth, an internationally vaunted founding father of Canadian comics. (See my review of Seth’s “Clyde Fans” here.) The acclaim is well deserved. Much like Sherwood Anderson, William Faulkner, and more recent and specifically Canadian writers exploring big conflicts writ small, such as Miriam Toews, “Shelterbelts” presents a radically compassionate portrait of very real people with very different views, all struggling to navigate change, whether they find that change too fast or too slow.

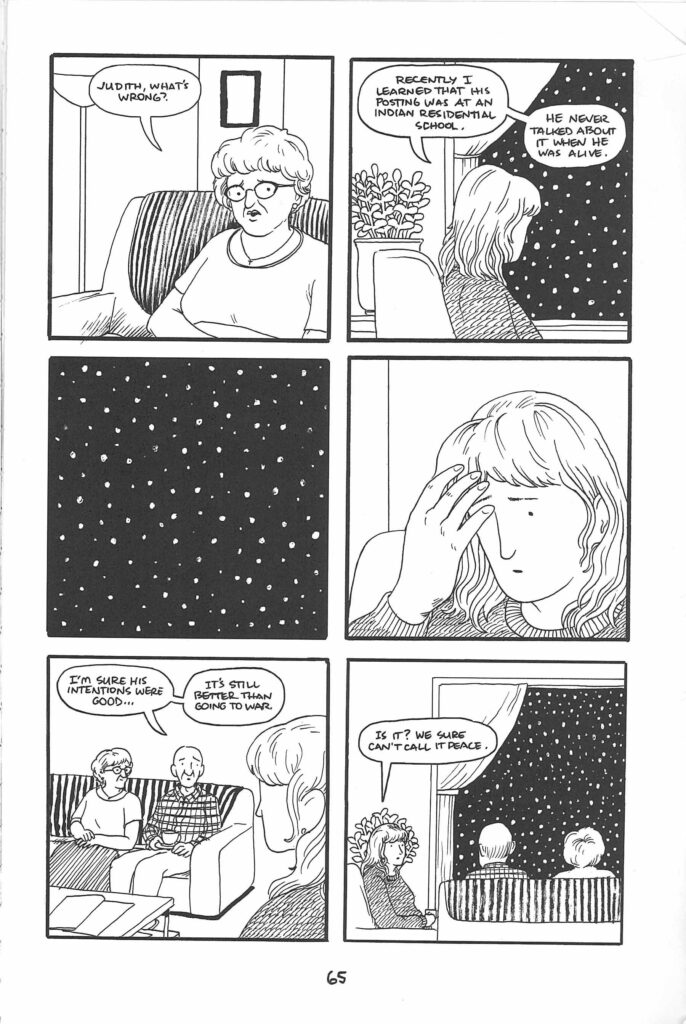

In this scene, for example, Judith, a young local teacher, hits a deer with her car—perhaps the same deer from the peaceful six-panel image above. Her car is stuck, and with a snowstorm in progress, a nearby elderly couple takes her in for the night. Unsurprisingly for this small town, the three of them quickly determine that even though they didn’t immediately recognize each other, their families have been interconnected for a long time. The conversation leads to pacifist Mennonite conscientious objectors (C.O.s) in World War II, who refused to bear arms, but took other service postings instead. Judith shares her discovery that her grandfather, a C.O., was assigned to teach at an “Indian” residential school that has since been exposed as abusive in its practices of forced assimilation.

As the discussion unfolds into increasingly difficult territory, the background lines and patterns—the man’s plaid shirt in front of the sofa stripes, for example—clash and revolve. Dyck’s expert six-panel composition shrinks, enlarges, and moves that dark window with the polka-dot snowflakes around a page otherwise dominated by whitespace. The characters’ stilted words are propelled forward in visual time as the conversation stutters and stalls.

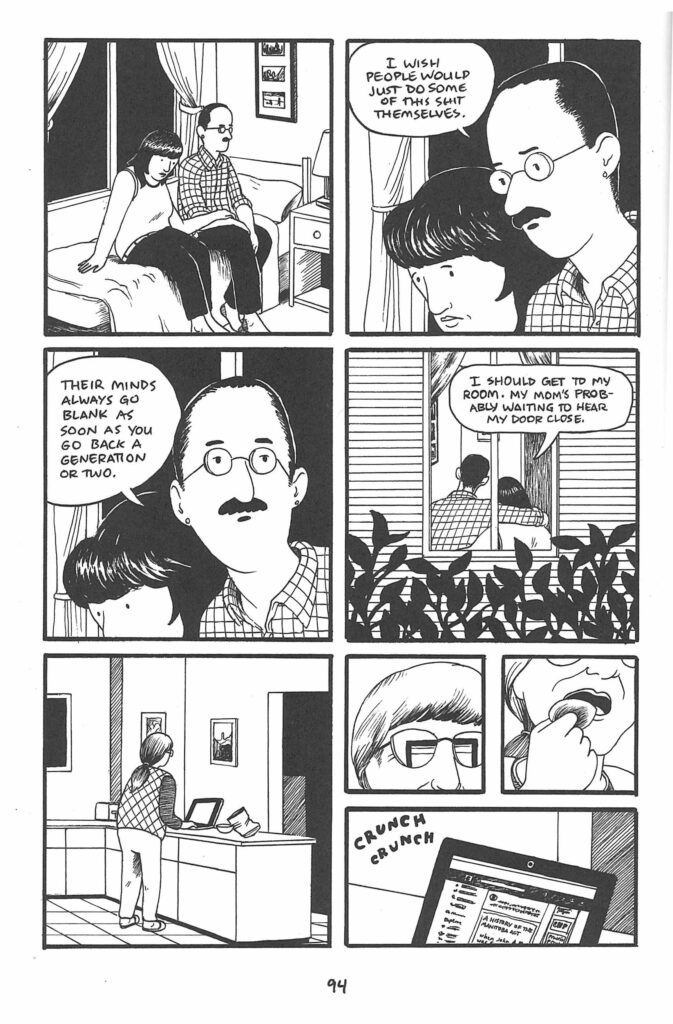

This book is largely about conflict and disagreement, it channels that energy through charged looks, furrowed brows, and churning backgrounds rather than direct confrontation. Not all of the silences in this book, however, portray conversational and ideological dead ends. In the story “Paper Bird,” for example, a Métis man dating a Mennonite woman tries to explain to the woman’s mother that the land was not “empty” when her Mennonite ancestors settled there, despite what her parents had told her. Later, alone with his girlfriend, he expresses exhaustion at having to repeatedly explain and re-explain Métis history.

Check out the headlines on the mom’s computer in the bottom tier, however. As she’s late-night snacking in the kitchen where the discussion took place, the mom reads an article about “A History of the Manitoba Act,” which promised but ultimately failed to grant much of Manitoba to the Métis when the province was created. The mom, unbeknownst to the Métis man, is fulfilling his wish by doing her own research.

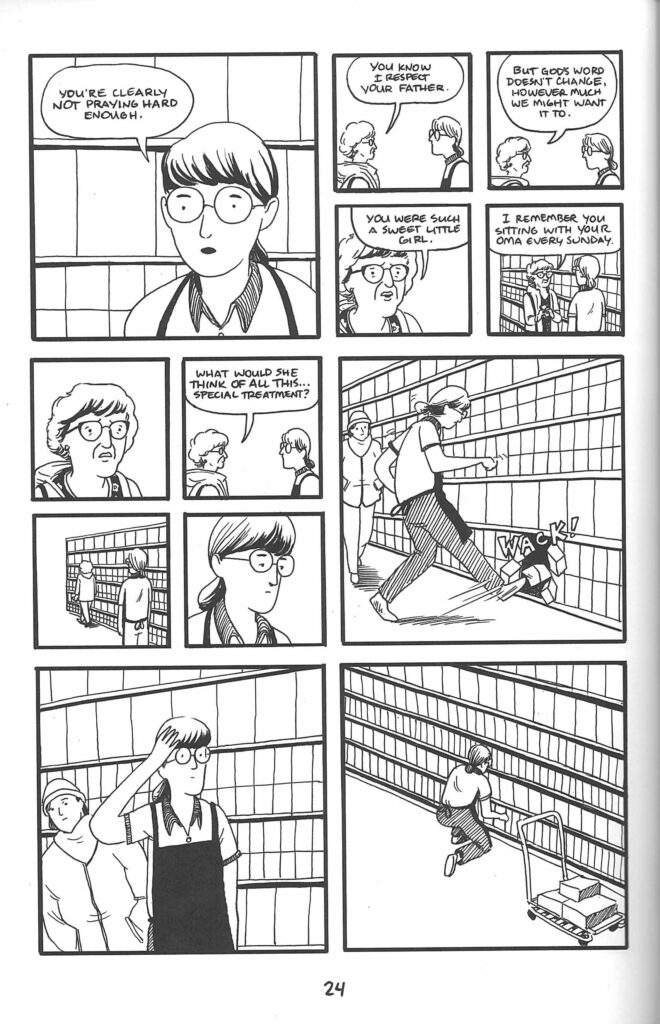

The worst casualty readers witness in this book (aside from the dead deer), is a low grocery shelf. This happens when the same woman who kindly takes in Judith in the snowstorm, begins to verbally abuse Jess, her former pastor’s gay daughter. “I’m praying for you,” she says, and Jess just can’t keep quiet:

As frustrating as some of these characters prove to be, “Shelterbelts” works not to excuse, but to humanize every character within its pages, from the farmer selling his land to pipeline developers, to the megachurch pastor who pushes a gay member to the fringes of his congregation. Readers still might disagree some characters, even violently, but we see—literally, in these comics—at least a hint of where each character is coming from. “Shelterbelts” practically overflows with compassion, but nevertheless resists easy solutions to its conundrums. At this time of social-media-fueled dehumanization and oversimplification of people whose views differ from our own, “Shelterbelts” reminds us, through its interwoven cast of characters good and bad, that most of us are trying, and could also stand to try harder.