It took Guy Delisle 15 years to complete Hostage. For two straight years of that 15, he drew a page a day of the story of Christophe André, a French citizen working for Doctors Without Borders. In 1997, André was kidnapped near Chechnya and held for ransom for three months.

Delisle certainly wasn’t held hostage by his work—although he did go so far as to chain himself to a radiator and have a friend take pictures, so that he could get the details right in his illustrations.

But the repetitive, day-to-day nature of building André’s story for those two years was intense, and the experience helped him convey its pace and monotony. As Delisle told an interviewer for The Paris Review this past July, “I want the reader to have the physical sensation of time passing. That’s why the book is four hundred pages.”

You won’t be held hostage by Delisle’s book, either. Hostage takes place mostly in a single room, but Delisle is such a master of the genre, that you’ll be reading on the edge of your seat. “This entire story will be over in no time,” André thinks at one point—a point when I still had a huge chunk of remaining pages in my right hand.

Knowing things that André doesn’t know is part of what creates such masterful tension in this book. But it also helps if you don’t know too much. This book will still read beautifully if you know the ending, but if you don’t yet, I recommend avoiding the spoiler reviews out there. I was certain that André would get out, but I wasn’t sure exactly how, which made for the most rare and delicious type of reading.

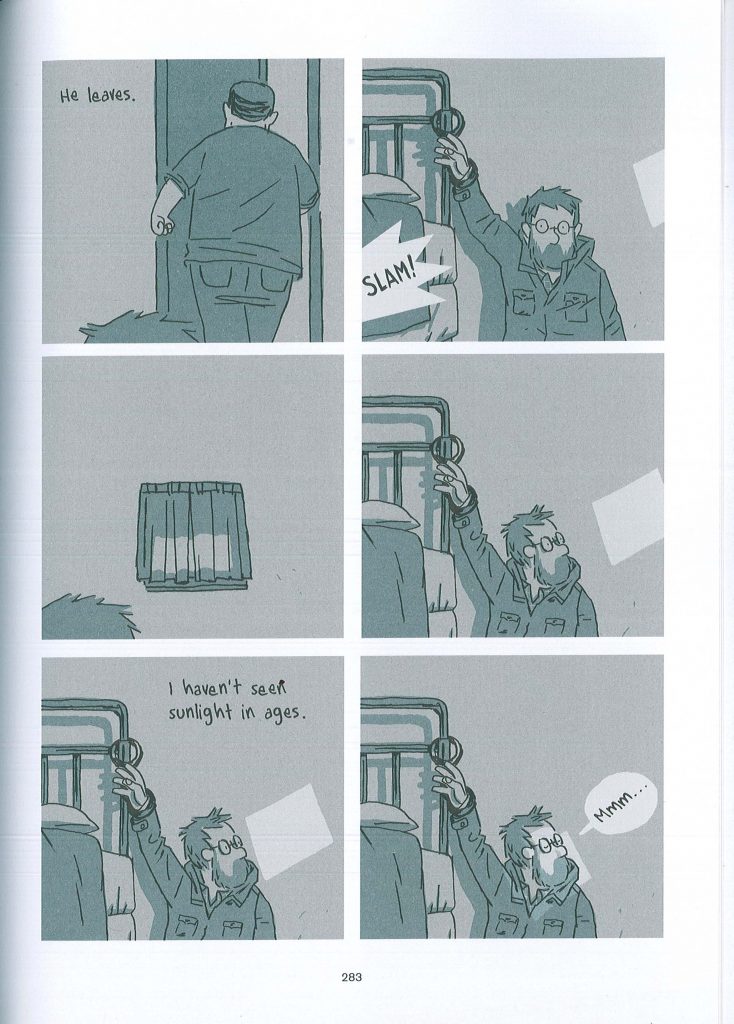

How else does Delisle manage to keep the book so exciting? How many different ways are there to draw the same, almost bare room? The same mattress, radiator, handcuffs, single window, ceiling, door?

Part of the answer lies in the unique tools at a comics artist’s disposal for creating energy and movement in scenes that seem otherwise static: perspectives and frames constantly shift, keeping us alert, even if the story itself is inherently slow.

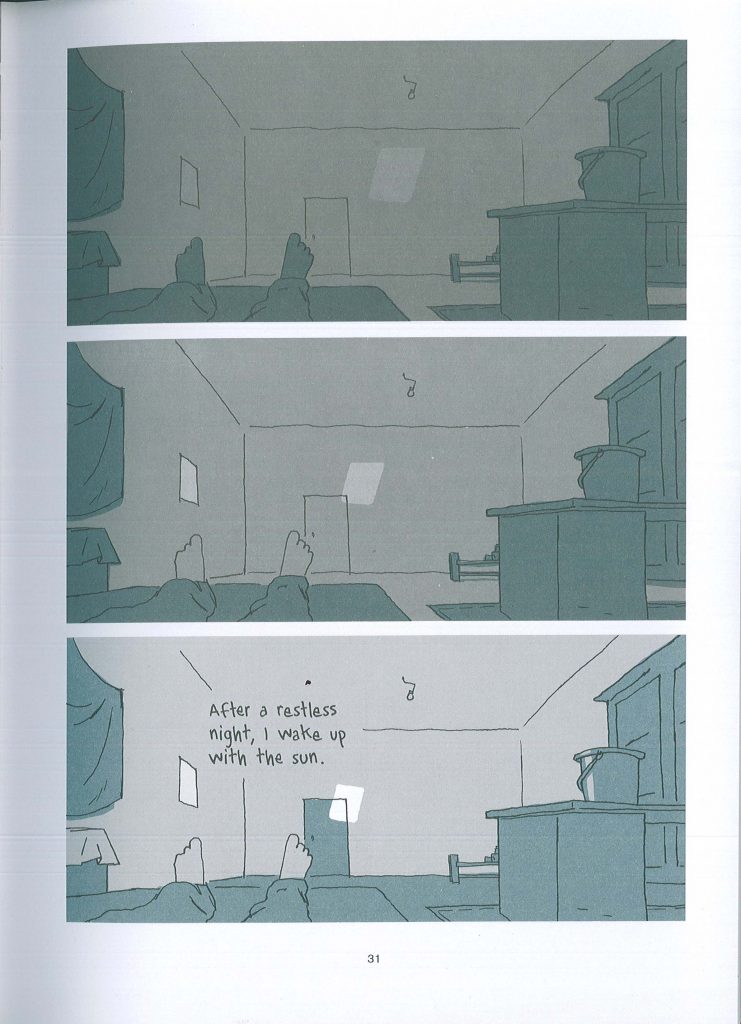

The reduction of visual clutter, too, forces readers to slow down and look for changes and details that they might not notice in a busier environment. Take a closer look at this page, for example:

On my first read, I didn’t notice that the room doesn’t lighten uniformly. Instead it lightens into distinctness: for instance, the cloth over the window remains dark, but the one under it brightens to white. Similarly, the door darkens rather than lightens, from light grey to slate. That parallelogram of sun not only moves, but straightens to square, and shares a bit of its illumination with the pail on the right.

When was the last time I had the luxury of studying the progress of light that carefully? Probably when I was a kid, lounging in bed on a lazy Saturday.

The radical simplicity of Delisle’s illustrations also encourages us to open up to more senses than just sight. On this page, for example, when André is transferred to a new location, he and I should both be anxious. Instead, however, I revel with him in the warmth of a square of sun that I swear I can feel on my skin, too:

Delisle has admitted that in André’s position, he’s pretty sure he would have gone crazy. It’s important to acknowledge that the vast majority of hostage situations don’t turn out as positive as André’s: part of why Delisle was drawn to tell André’s story in the first place is that André seemed to have a rare reaction, growing stronger from his experience rather than being beaten down. The epilogue notes that André was back in action for Doctors without Borders only six months after the end of his ordeal.

Ironic, then, given how psychologically destructive most hostage situations turn out, that part of the book’s success lies in its therapeutic value for its readers—for this reader, at least.

In the course of my online research for Hostage, mostly on supposedly “literary” sites, the video ads that my browser wouldn’t let me block made it hard for me to read. I finally found my post-it notes, and slapped them on my screen to cover up the visual noise so I could read in peace. Making my way through Hostage, however: surprisingly calming and meditative, despite the book’s suspense.

By no means do I want to trivialize the experience of André and other hostages. But a quiet, spare book like Hostage, despite its stressful topic, is a welcome relief in an overstimulated world.

André’s escape suggests that maybe there’s hope for escape for us, too, from the destructive elements in our lives that hold us hostage, that have more power over us than we’d like to acknowledge—but which we have more power over than we might be able to see.

After my gushing about simplicity, however, be warned for a bit of visual whiplash in my next post. Lorena Alvarez’s Nightlights is positively lush, busy, and gorgeous—and I love it just as much as Hostage:

Thanks so much to Better World Books in Goshen

for always providing a welcome place of respite with its comfy chairs, and shelves and shelves of stories. You can find all of the books I review there, too, and order (for free!) any that you can’t find in the store.