I’ve been gradually re-posting my archived material from the Elkhart Truth’s defunct Community Blogs. This week I’m resurrecting this 2014 review of Lynda Barry’s “Syllabus” because my Goshen-area readers have a unique opportunity to see some original pages from this work between now and December 31 at the South Bend Museum of Art. Barry and a slew of other comics luminaries are part of the exhibit “Best American Comics Selections: 2014-2017,” a showcase of work featured in the past three years of the anthology, which was added to Houghton Mifflin’s Best American series in 2006. You can also see original artwork from Chris Ware’s “Building Stories,” which was the very first book I reviewed on this blog.

While you’re there, check out the related exhibit “The Funnies: Vintage Comics 1940s–1960s,” which features classic strips from Archie, Peanuts, and Dick Tracy—the original superhero—to Brenda Starr, whose creator Dale Messick was born in South Bend. For that exhibit, do be prepared for some challenging racial and gendered visual stereotyping, which was “normal” for the time, but can feel out of touch and even offensive now. It’s fascinating to meander through these exhibits side by side, and see how far the genre has come.

Stay tuned for a review of Gabrielle Bell’s “Everything Is Flammable” in two weeks. If you’re feeling impatient, here’s a video of teaser of her discussing her early work for The Paris Review. Enjoy!

Draw for Your Life: “Syllabus: Notes from an Accidental Professor,” by Lynda Barry

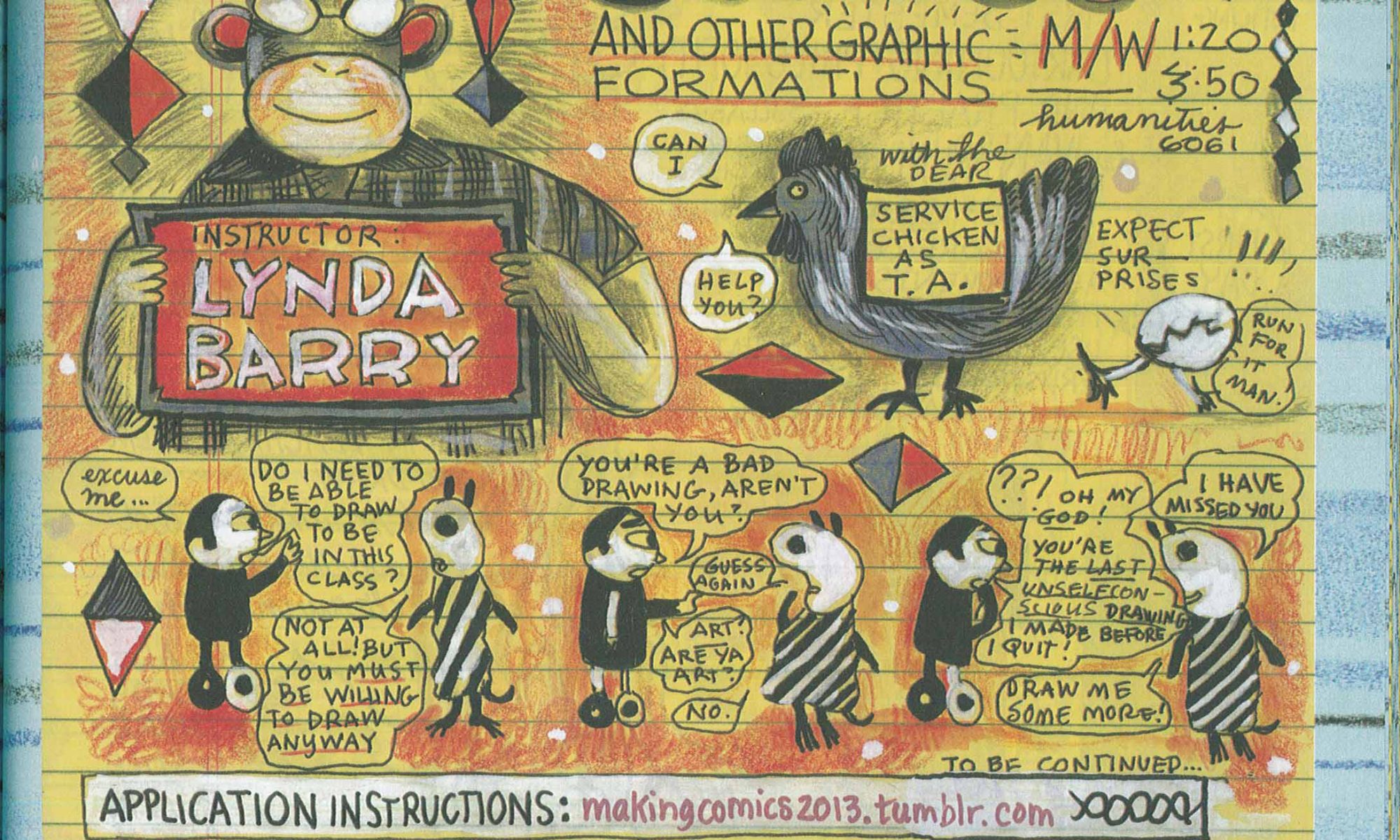

Pick up Lynda Barry’s “Syllabus” for the first time, and it takes a while to figure out what exactly you’re holding. There’s no “file under” categorization on the back, and no explanatory blurb inside the front dust jacket because there is no dust jacket, just a cardboard composition book cover with doodles and scribbles and publishing information that looks hand cut and pasted like a ransom note.

Even if you don’t recognize Barry’s inimitable style on the cover of “Syllabus,” you’ll want to pick this book up—you’ll be drawn to pick it up—because before you have a chance to read it and realize that it’s one of the best books of 2014, you’ll want to return it to the hapless doodling schoolkid who left it in the comics section of the bookstore by mistake.

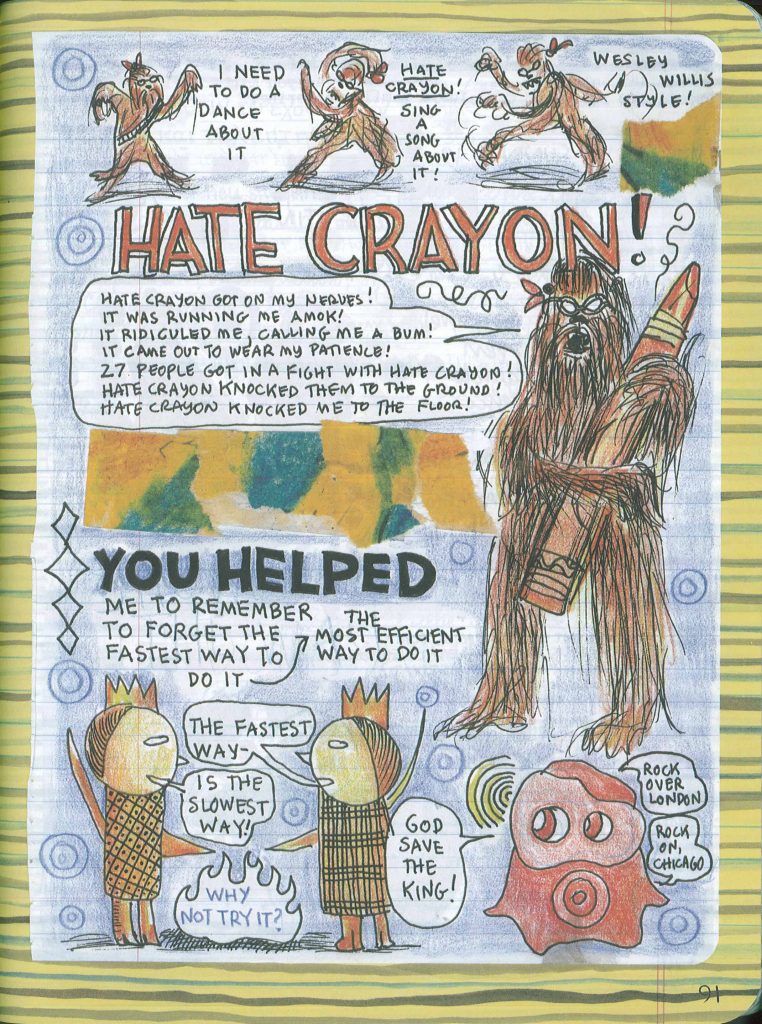

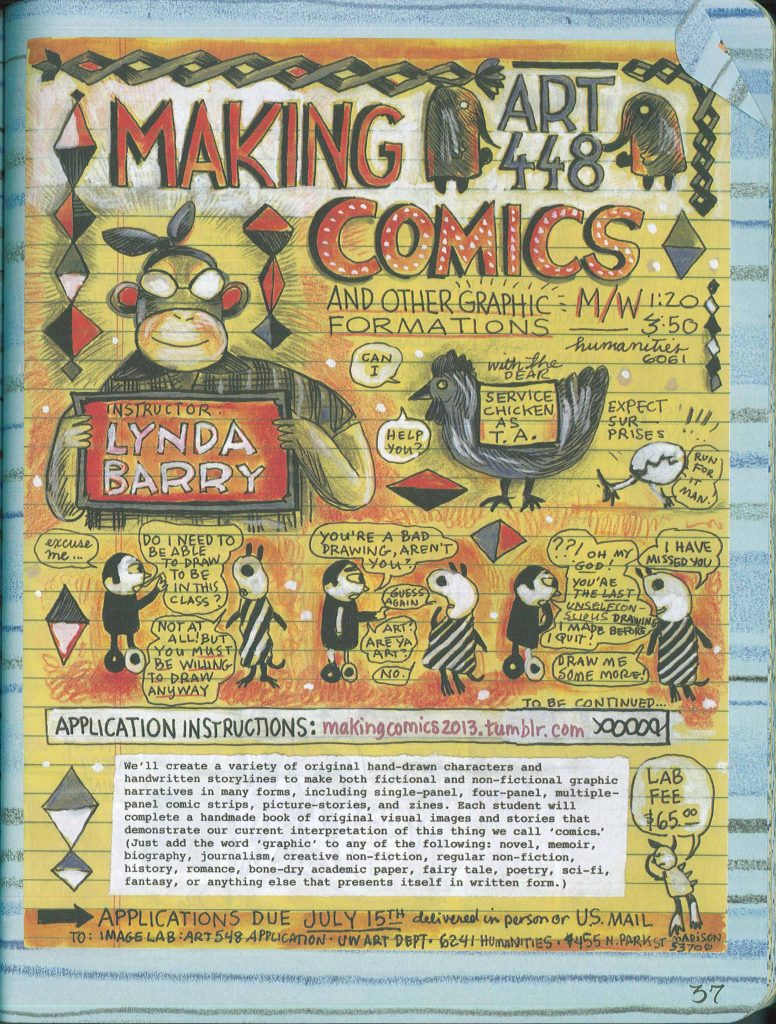

Lynda Barry is still a doodling schoolkid at heart. She simply does what she does even if it doesn’t fit neatly into a bookstore genre—which is precisely what makes her work so beautiful, inspiring, and powerful. Known to her students as “professor long-title,” Professor Chewbacca, Professor Old Skull, or some other bizarre name that changes every semester, Barry compiled this book of lesson plans, musings, and activities, out of assignments from her classes and workshops at University of Wisconsin-Madison and elsewhere. Barry is first and foremost invested in inspiring people to draw, write, and create art. In the process of rekindling its readers’ impulse to draw, it also meanders its way around much more important questions than genre: What is art? What’s an image? Why are drawing and creative writing so crucial not just to individual well being, but to the health of society and humanity?

Barry has been working for decades to answer questions like these through teaching, writing, and comics, but she stepped up her efforts in the spring of 2012, when she began working at UW Madison as a visiting artist. Her credentials are as ill-categorizeable as her work: the bio page on her agent’s website lists her as a “painter, cartoonist, writer, illustrator, playwright, editor, commentator and teacher,” and she’s now an Assistant Professor of Interdisciplinary Creativity, a title that she usually makes fun of or simply refuses to invoke. Her most recent bestseller, “What It Is,” was the first of a series of genre-defying books much like “Syllabus”: part memoir, part activity book, part theoretical musing about the nature of art.

Although Barry gained broader recognition fairly recently, she is not new to comics: she drew the weekly series “Ernie Pook’s Comeek” for thirty years (check out collections like “The Greatest of Marlys” and “The Freddie Stories”). In a time before online comics, those of us lucky enough to have access to free urban papers like “The Chicago Reader” fell in love with Barry’s bizarre and endearing characters: young outsiders like Marlys and Freddie as well as creatures like the precocious poodle Fred Milton, a character from a bizarro alternate universe version of “Winnie the Pooh.”

Barry’s road to recognition in the larger comics and art worlds was slow in coming—she just had her first solo show in New York City in the summer of 2014—but critics and fellow cartoonists have been gushing about her work for years.

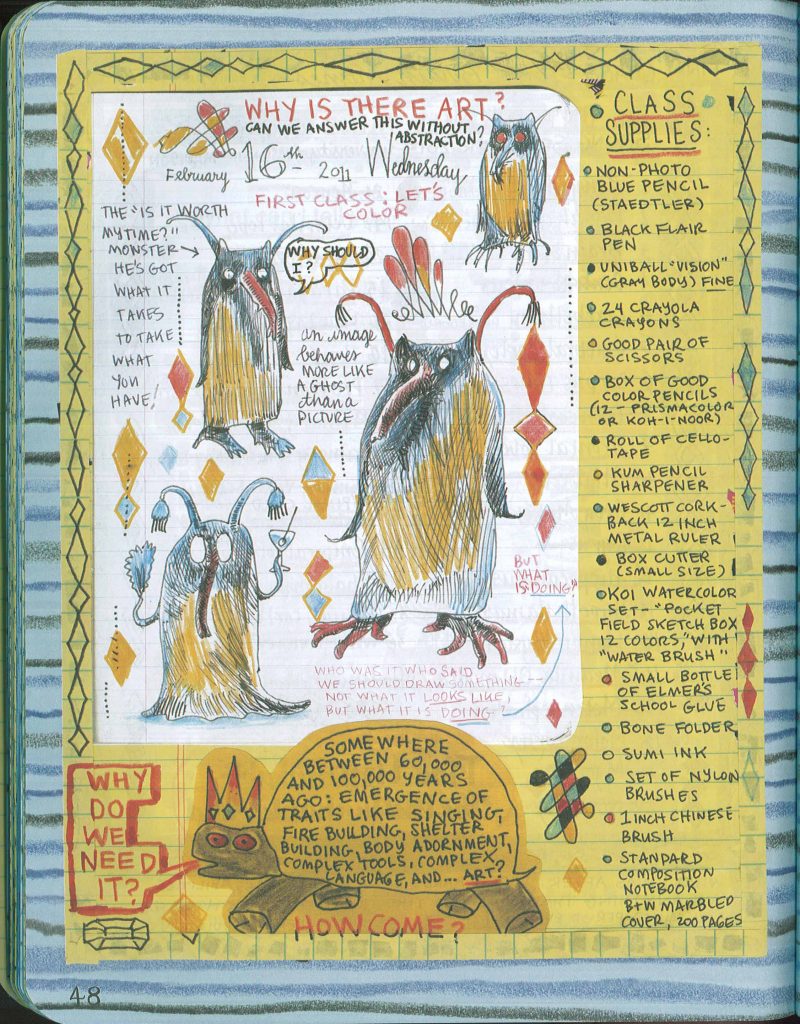

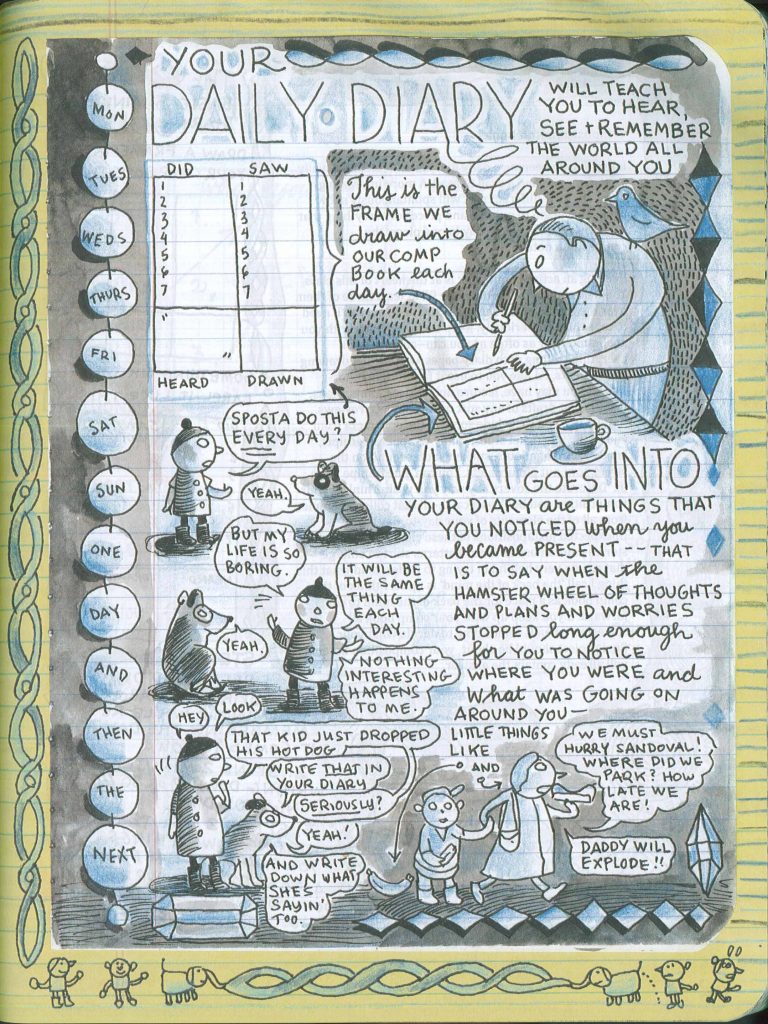

I teach creative writing and graphic novels, so I find lesson plans more interesting than the average reader might. I devoured this book from cover to cover, but it’s also great to flip through and read in whatever order you like—especially since Barry’s lesson plans, assignment sheets, and even syllabus pages like the one below, are artworks in their own right.

Two of Barry’s constant and most inspiring refrains are that 1) no artistic practice is a waste of time, and 2) any worthwhile work takes time—sometimes a long time. Her classes have been called boot camps, because in addition to her major assignments—from hour-long coloring projects to story-writing—she requires daily diaries and weekly memorization exercises, usually of Emily Dickinson poems. Poetry memorization in an art class? But Barry firmly believes in the worth of developing an artistic practice, which takes practice, even if the particular steps to building that practice confer no obvious, immediate benefit. Her answer to the students who balk at these exercises? See the “Is it worth my time?” monster in the image above.

Yet despite this philosophy that art takes as long as it takes, Barry also acknowledges that her students and readers have busy and complicated lives; she does want to make the work not just challenging, but doable. To that end, daily diaries and other activities have time limits, anywhere from five to ten minutes.

I also highly recommend this book for teachers in any discipline. Barry is a sensitive and reflective teacher, and she willingly shares her failures as well as her successes. Rather than railing against her students when an assignment that went well in one semester doesn’t go well with a new set of students, Barry thinks—and draws—through her failures to look for solutions.

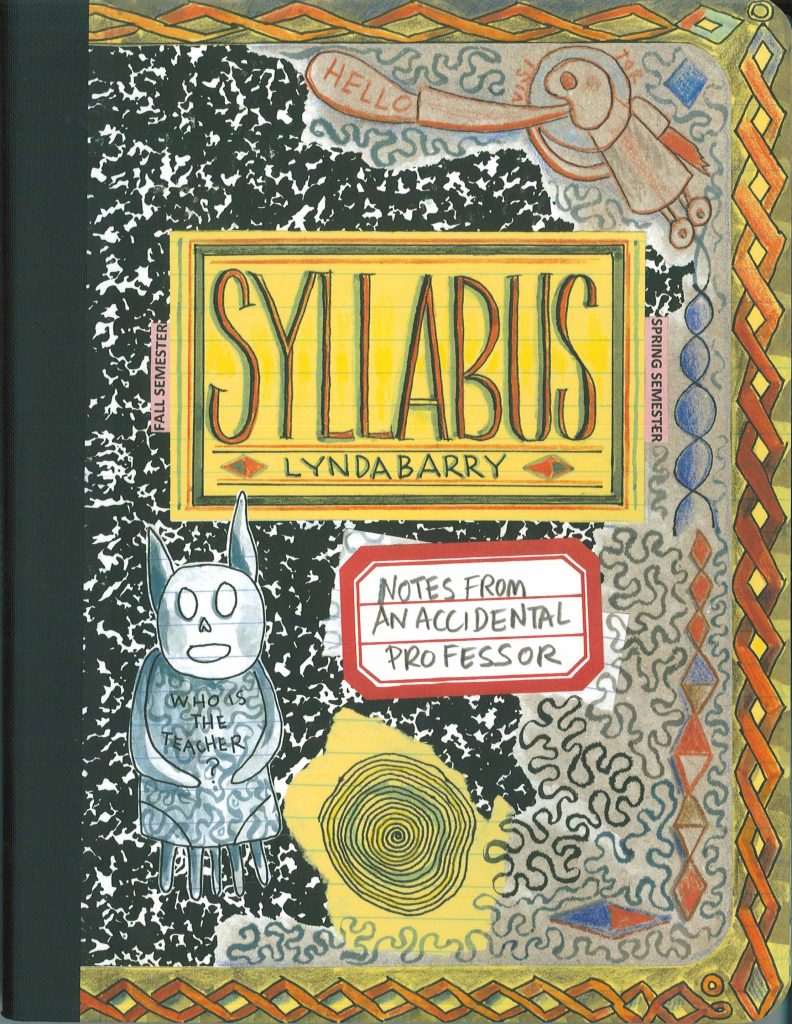

Barry also reminded me to question what my students really need from a class, and to focus my assignments, grades, and class activities around developing those skills. Especially since she actively recruits students who claim that they “can’t” draw, Barry repeatedly stresses that student work is graded on effort and time, not on purported skill. Here, for example, is a flyer advertising her “Making Comics” class:

Barry sincerely loves her students’ drawings, whether awkward or accomplished, and “Syllabus” includes many of these drawings. Thus, a lot of the art in the book will make any reader say, “Well, I can do better than that”—which is precisely what Barry was hoping you’d say, especially if that reaction encourages you to pick up a pen—or a crayon—and give it a shot.

“Draw me some more! I have missed you,” says “the last unselfconscious drawing I made before I quit” in the panel above. For Barry, drawing, as well as the arts more generally, are as much about survival as play. “I don’t think there’s any other reason we have art than to save us, the way our liver is there to keep us alive,” she said in the June 2014 interview about her solo show linked above.

Save yourself! Check out this book! Even if you don’t pick up a pen, let Barry’s contagious enthusiasm wash into the rest of your life, and you just might return to that artistic project—novel? symphony? interpretive dance cycle?—that you’ve been meaning to finish for years.

As always, thanks to Better World Books, 215 S. Main St. in Goshen, for providing me with books to review. You can find all of these books at the store.