Originally published on GoshenCommons.org October 29, 2013

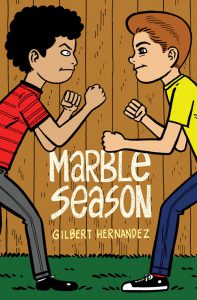

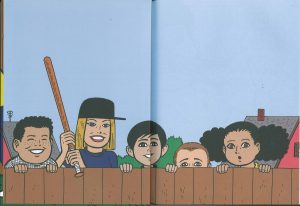

We’ve been discussing color comics almost exclusively, so I’ll start this review with the only color pictures in the book, so you don’t feel like Dorothy returning to colorless Kansas. Here are the cover and inside cover of “Marble Season,” by Gilbert Hernandez:

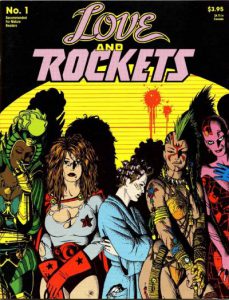

Hernandez has been pioneering comics since the 80s, when he began co-writing the punk-inspired series “Love and Rockets” with his brothers Jamie and Mario, and has recently been embarking on more solo projects. Most acclaimed is “Palomar,” a sweeping spinoff series from “Love and Rockets” about a fictional Latin American town. Although Hernandez is sometimes criticized for drawing anatomically unlikely women, he has a dedicated following of female readers. The women in his stories almost always prove to be strong and multidimensional beneath their bombshell exteriors.

Second image from grovel.com.uk

Hernandez has often been compared to Gabriel Garcia Marquez, and on the back-cover blurb for “Marble Season,” Pulitzer Prize-winning writer Junot Diaz calls him “one of the greatest American storytellers” —but don’t expect “One Hundred Years of Solitude” from this book. Like the experience of childhood, Hernandez’s semi-autobiographical story of California in the 60s is fragmented, episodic, and sometimes just plain weird. But also like childhood, the narrative is rich, layered, and emotionally intense. It’s also about comics, as Hernandez makes clear on his very first page (see below), and in a page of footnotes at the end that detail and explain the references to comics and other pop culture.

“Marble Season” is deceptively simple. The action cuts quickly—like a kid with a short attention span—from scene to scene, character to character. Yet we also get crucial flashes of history changing around these characters, and the role of image media in those changes:

That kid’s cut-off head at the bottom of the frame is a great illustration of Hernandez’s subtlety. It’s funny and cute, but also a powerful reminder of how all of us felt at some point when we were little, listening in on conversations we only half understood. Hernandez also takes advantage of kid innocence to address difficult issues like racism simply but directly. Anyone who hasn’t too deeply repressed the drifting loyalties of kid groups, their instant and illogical insider/outsider shifts, can relate to his main character in the following scene:

But what makes Hernandez’s work so effective is his restraint. He doesn’t dwell on this moment, and he doesn’t need to—we get it, and we also get how quickly kid moods can shift from dark back to silly:

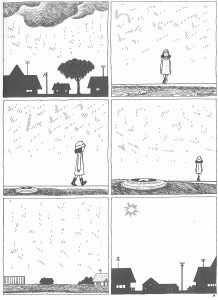

Hernandez’s characters sit right on the edge of adulthood, and it’s their precarious position, their tenuous hold on their innocence, that keeps readers rooting for them. Hernandez’s expert pacing shifts also slow us down every once in a while, reminding us that childhood isn’t all about action—an awful lot of kid time is spent waiting and watching:

I wasn’t ready to let these characters go. Let’s hope this book is the beginning of another series on par with “Palomar.”

See you in two weeks, when I’ll delve more deeply into the power of black and white comics. In the meantime, check out the comics section downstairs at Better World Books in Goshen, Indiana, and keep those comments and suggestions coming!