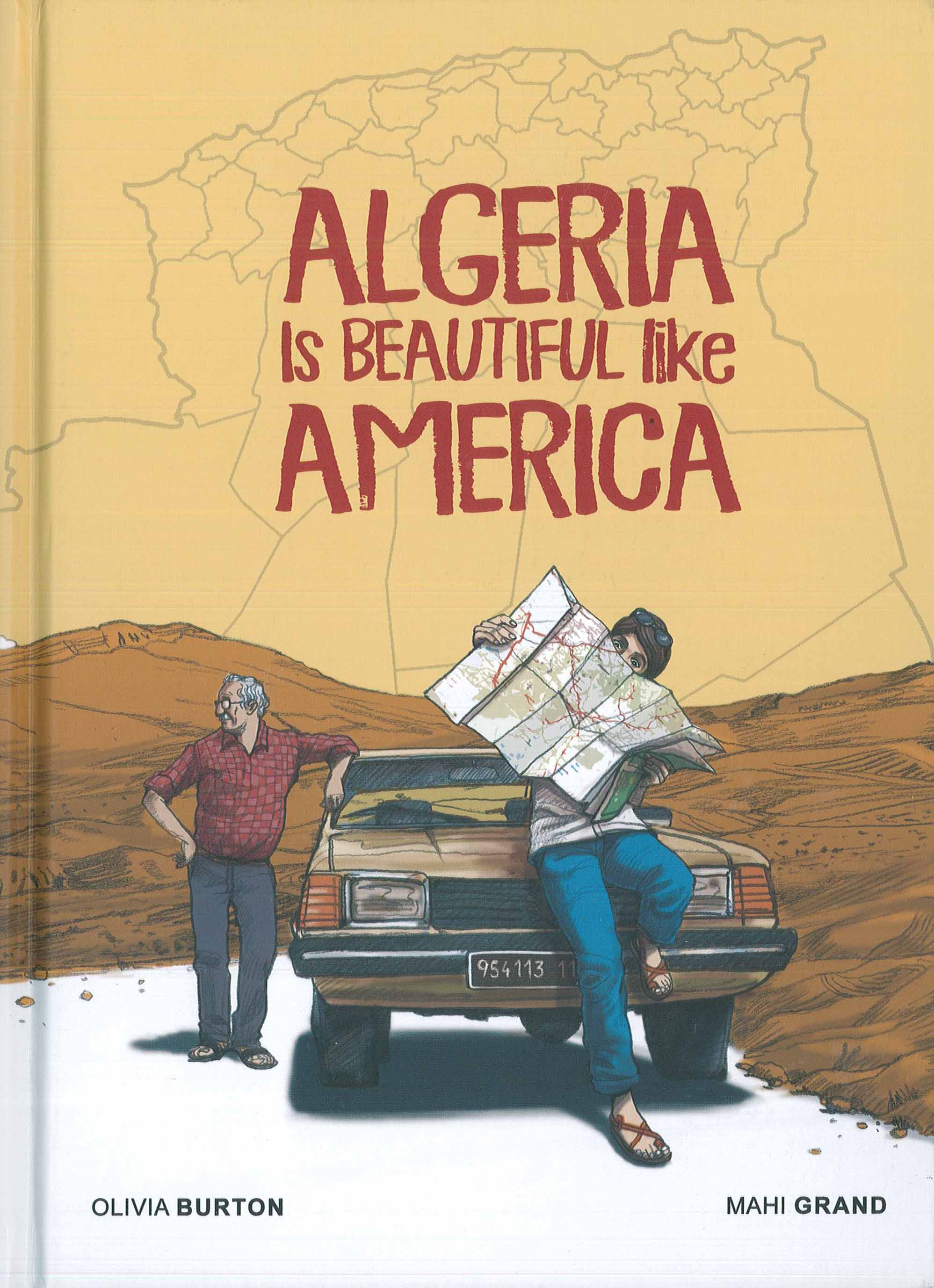

“Algeria Is Beautiful Like America,” by Olivia Burton, illustrated by Mahi Grand. Trans. Edward Gauvin. 176 pages, Lion Forge, April 2018. Hardcover, list price $24.99.

Thanks to Better World Books, 215 S. Main St. in Goshen, for providing me with books to review. You can find or order all of the books I review at the store.

Travel memoirs are a difficult genre to write well. The worst ones devolve into solipsism: too much about the narrator’s emotional landscape, when it’s likely the landscape of the location that drew the reader to the book in the first place. Yet the author can’t back off too much, lest the book desiccate into a daily calendar of events, or worse, a mere guidebook.

This balance between narration and location becomes trickiest on contested ground. “Algeria Is Beautiful Like America,” written by Olivia Burton and illustrated by Mahi Grand, was originally released three years ago in France, where a complicated colonial history with Algeria lives very much in the present. Newly translated and released in the US this past April by Lion Forge, the book explores Algeria through the lens of Burton’s family history—a lens that doesn’t always make for a pretty picture.

Burton grew up in France hearing stories about Algeria from her mother and grandmother, who lived in Algeria’s Aures mountains. Alternately dazzling, terrifying, and confusing, the stories that shaped Burton’s childhood narrated their lives as French colonists in Algeria, collectively referred to as Pied-Noir, or Black Foot settlers. Burton had never thought much about the name, or about her family’s connection to Algeria until she began high school in France. When she first told her new friends about her heritage, one of them responded, “Well, you don’t look like an Arab!” “I suddenly felt very uncomfortable,” Burton recalls.

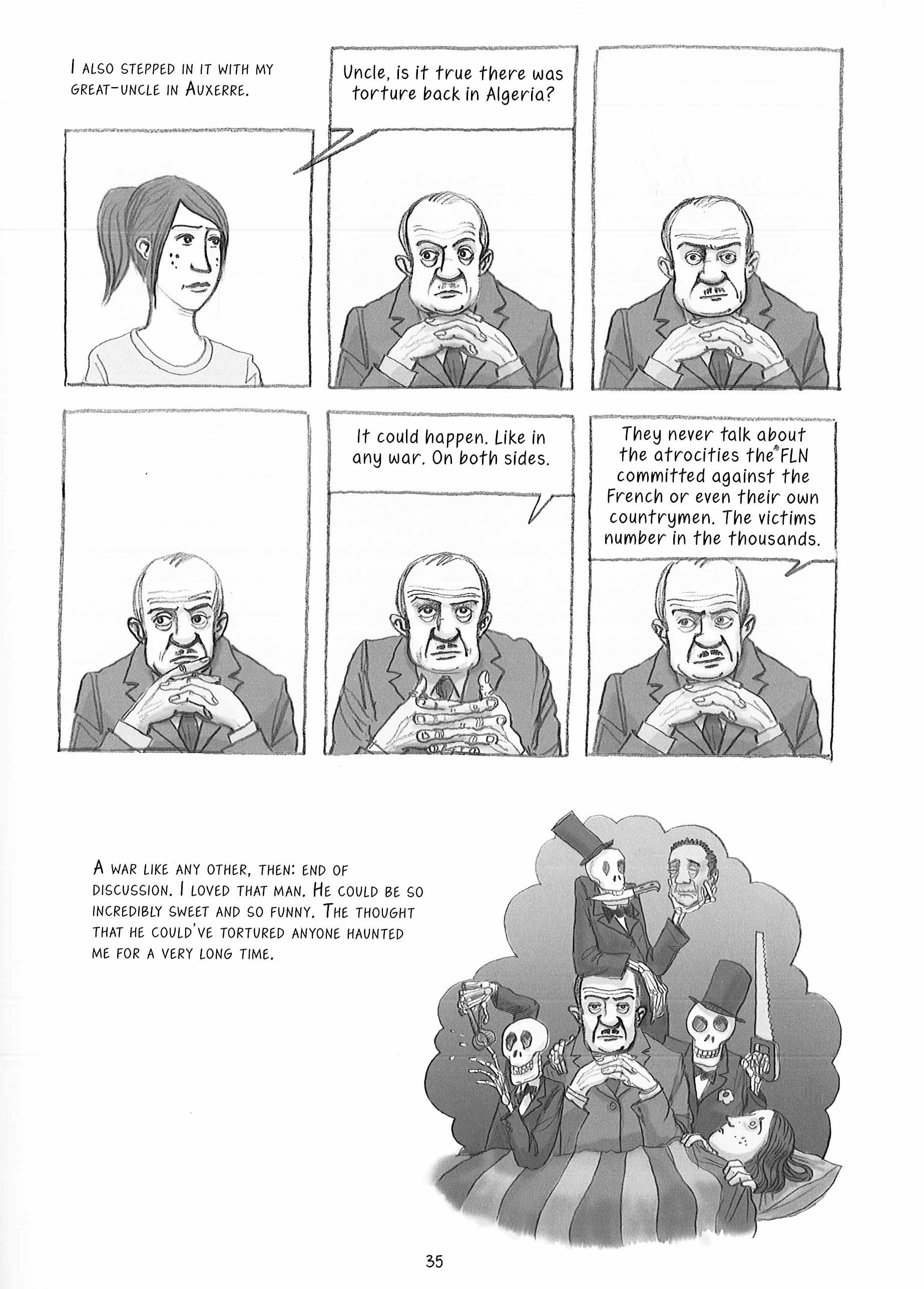

As might be expected, Burton’s confusion and discomfort heightened in college, where her left-leaning friends shared what they had learned about Black Foots, calling them “racist exploiters, fascists . . . torturers, even. I had a hard time placing those descriptions with what I knew about my family,” she writes. “I didn’t know whom to side with anymore.”

Burton learns more in college about the Algerian battle for independence, fought from 1954 to 1962, and driven largely by the FLN, the Algerian National Liberation Front. The more information she gathers, the more challenging her questions for her family become.

Burton’s increasing understanding of her family’s role in an oppressive colonial history haunts her as she develops a more nuanced political consciousness. Burton could easily have used her family’s history as an excuse to sweep France’s colonial crimes under the rug—and for a while, overwhelmed by the clashing perspectives, she does lapse into silence.

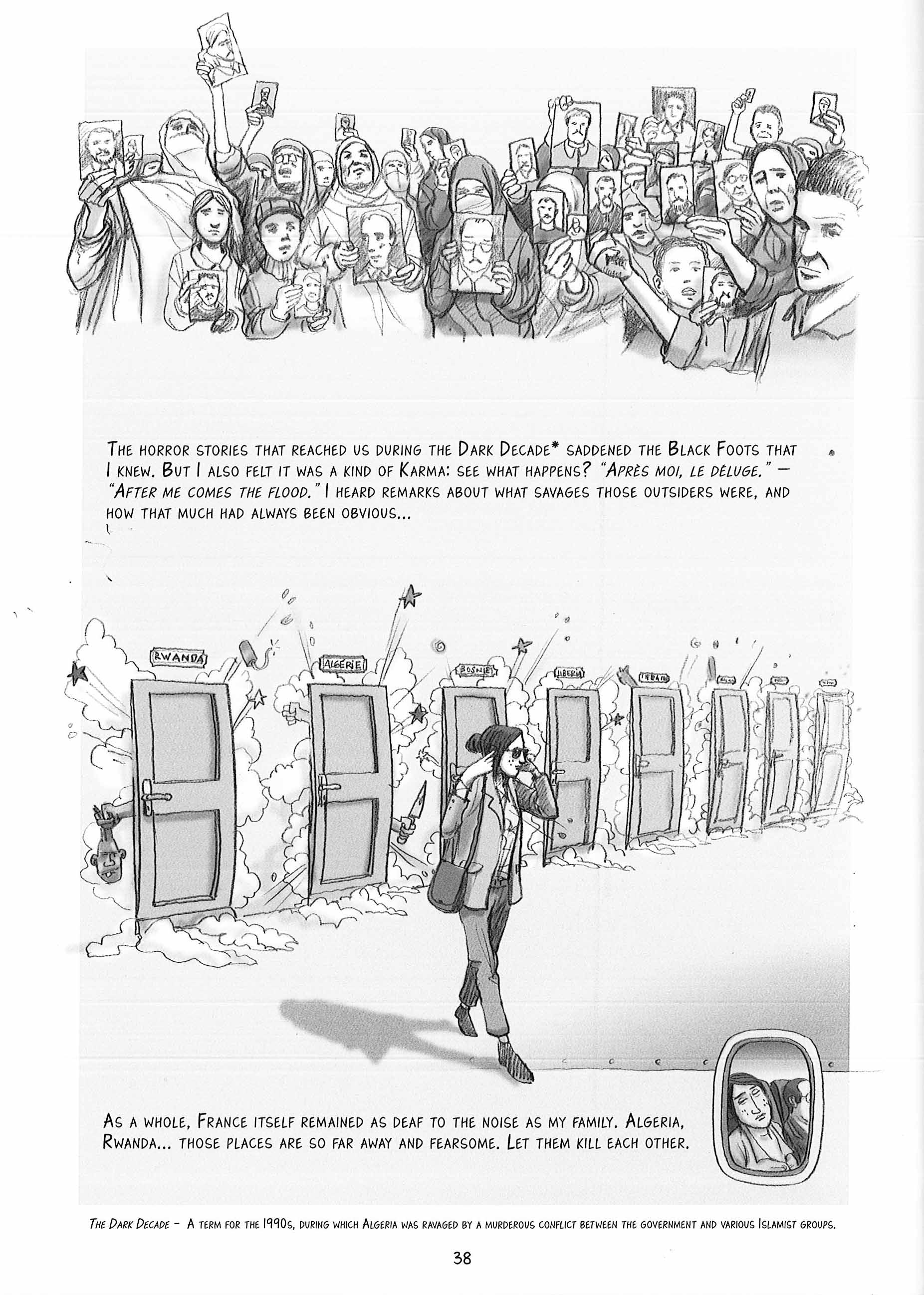

For years, she writes, “at the mere mention of the word ‘Algeria,’ my heartbeat sped up. I had inherited a war I hadn’t experienced.” As Algeria headed into the 1990s—referred to as “the dark decade,” a bloody, extended clash between Islamic groups and the government—Burton continues to live her life as a professor safe in France, keeping Algeria submerged in the depths of her consciousness:

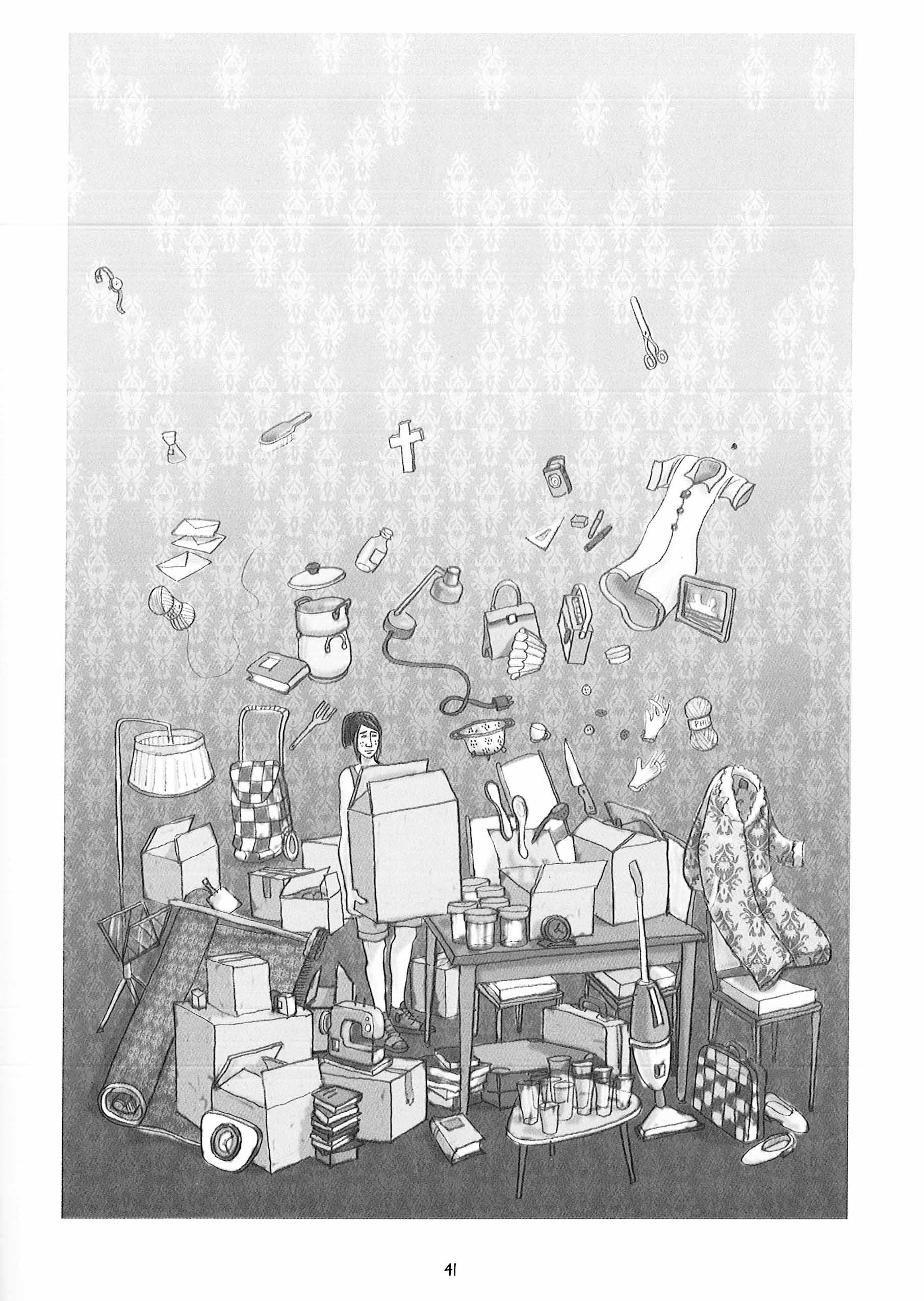

It takes her grandmother’s death to spur Burton to finally face her roots in Algeria head on. When Burton begins to sort through her grandmother’s possessions, she’s surprised by how few come from Algeria, despite the fact that her grandmother had lived there for fifty years. Grand’s illustration of Burton’s grief and disorientation puts the genre of comics to its best use, showing in expert shorthand rather than spelling out the way psychology bleeds into lived reality:

Burton’s search through her grandmother’s effects isn’t as futile as the illustration suggests, however: in an envelope labeled “For Olivia,” she finds pages and pages of her grandmother’s handwritten memories about Algeria. Burton had repeatedly asked for her grandmother to write these stories down, and had become convinced that her grandmother had ignored her requests.

Ten years later, Burton takes these pages with her on her first visit to Algeria, hoping to see in person the places she’d been hearing about from her mother and grandmother all her life. Burton also searches for the straight answers she never got from any of the members of her family.

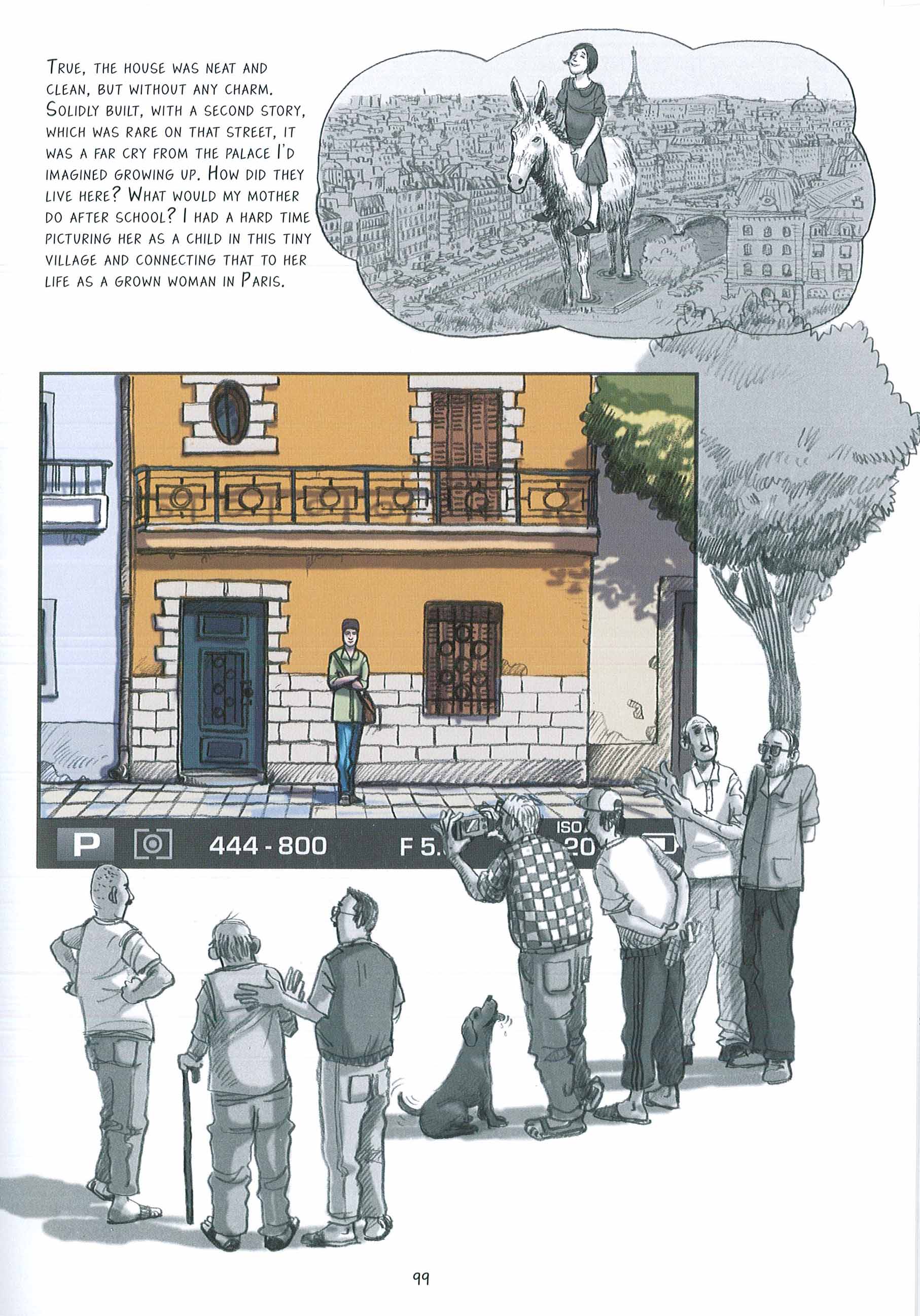

With the help of a guide, Djaffar—like Dante’s Virgil, the reviewer for “The Comics Journal” observes—Burton finally arrives at the house her mother grew up in, in the Algerian village of Merouana.

Or at least she’s pretty sure it’s the same house. Burton wrestles throughout the rest of the story with questions of authenticity, which Grand’s illustrations help her explore. Except for the cover, the only color in the book are drawings of Burton’s color photos from her trip, which are always drawn to include the frame of the print—a subtle yet expert comment on the power of nostalgia to “color” and distort memory.

For some reviewers well-acquainted with Algeria’s bloody fight for independence, and especially with the acclaimed 1966 film about the revolution, the “Battle of Algiers,” Burton glosses over too much of Algeria’s revolutionary history in favor of reconciling her own personal guilt. (See, for example, The “Comics Journal” review linked above.)

The response to this US release has been positive overall, however. Most notably, African-American reviewers for Black Nerd Problems and Comic Crusaders, on the other hand, find Burton’s honest expressions of discomfort palpable and powerful.

One recurring quibble with the book is that it has little or nothing to do with America, despite the title’s suggestion. To me, however, Burton means to reference a balance of beauty and fraught history shared by both countries.

Yes, America is beautiful. Yes, it’s also a beauty that too often glosses over our history’s most hideous chapters. I learned a lot from this book. It’s billed as a travelogue more than a history lesson, but it’s both—and more. It also suggests one possible example of how the US can move forward with full acknowledgement of our own colonial history, and its role in our very real—still unresolved, still largely racist—present.