“Killing and Dying,” by Adrian Tomine. 128 pp. Drawn and Quarterly. Paper, $19.95. Adult.

Thanks to Better World Books, 215 S. Main St. in Goshen, for providing me with books to review. You can find all of the books I review at the store.

This review was originally written for the “Elkhart Truth” in spring of 2016, just before they discontinued their community blogs. I’m posting it now because “Killing and Dying” just came out in paperback, AND because Tomine is an important precursor to Nick Drnaso, whose “Sabrina” I’ll be reviewing in September.

Adrian Tomine doesn’t want to lose his edge. The graphic novelist and artist known for his royally flawed characters and dark storylines was especially worried about becoming a new parent—he was afraid he’d become a softie. So, while most brand new parents are thrilled to collapse into their own beds when they first return home from the hospital, Tomine instead stayed up to watch some art films—a series so bleak that they made even his “Vulture” interviewer shudder a bit.

As you might guess from the title of his newest collection, “Killing and Dying,” Tomine has managed to retain a fairly unflinching view of the world—and yes, as you also might guess, these storylines are definitely for adults. Think Stanley Kubrick and David Lynch—whom Tomine cites as two of his main influences—translated into weird, enveloping, and often disturbing graphic narrative vignettes.

Tomine has been producing these paeans to life’s most uncomfortable moments since he was 16, when he began his series Optic Nerve. Now hailed as a master of the genre, his messed-up characters have grown along with him, from teendom to middle age. Killing and Dying, released Fall 2015, is his fifth Optic Nerve collection, his first in almost ten years, since Shortcomings in 2007.

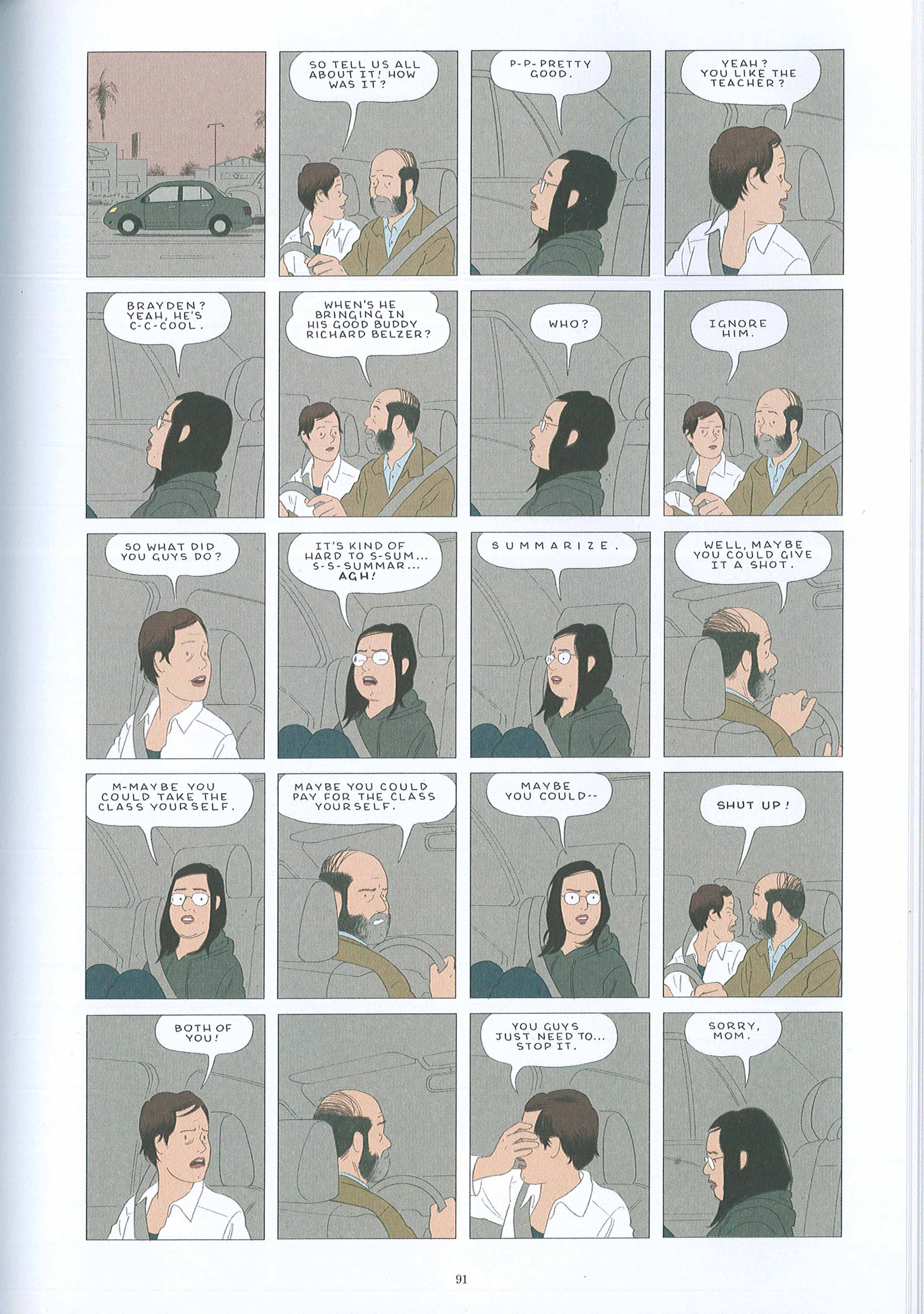

Yet while Kubrick or Lynch deal mostly in gruesome violence, Tomine’s specialty is gruesome awkwardness. The title story is about an aspiring young stand-up comic—thus, “killing” refers to a joke, and “dying” to being stranded onstage during a poor performance. “Dying” also refers to the matriarch of the story, who is dying of a terminal illness, while her husband and her daughter (the young comic) try, and largely fail, to hold the family together without her. The whole story is so wrenching, it might make readers wonder if actual physical violence would have been more palatable. In this scene, for example, the daughter has just taken her first comedy class.

The two frames of the mom’s face on the left side of the page are just one example of why Tomine’s work is so impressive even when he’s working in one of his more simplistic styles. Hardly anything changes between those two panels, but the character’s enthusiasm and deflation are palpable.

The number of frames, or panels, per page also has a subtle, yet powerful effect. The twenty-panel format makes this story, visually, look like a Sunday Funnies-style strip—think Charles Schulz’s Peanuts—and it even pushes beyond that standard, since Peanuts usually maxes out at 12 or 16 panels per page. More panels per page usually means more action, more punchlines, or both. Here, however, Tomine uses multiple frames to emphasize emotional claustrophobia, an effect heightened by the restricted color palette of browns and grays.

From story to story, Tomine changes his visual style so dramatically that this book could be mistaken for an anthology written and drawn by multiple artists. In each of the six stories in this collection, he tries out a different panel structure, color palette, level of realism, and pacing—but he does it all so subtly, and with such encompassing stories and characters, that you don’t tend to notice these details while you’re reading.

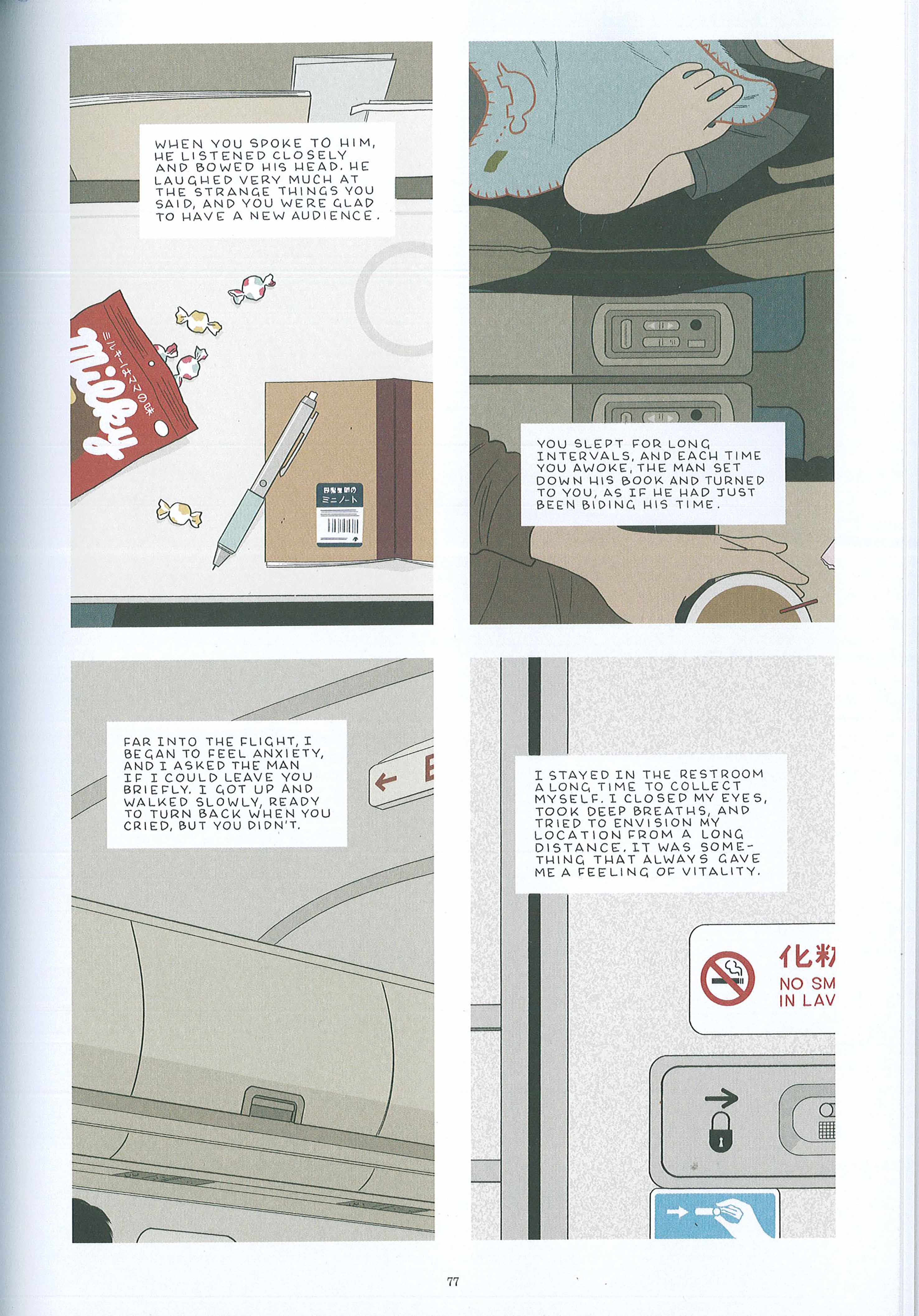

Contrast the pacing and style of the title story, for example, to “Translated, from the Japanese,” in which Tomine spirals time out of its traditional progression by counterposing a narrative from the past with bold colors, strong lines, and realistic, though fragmented, drawings. The words are a letter from mother to son, but the images, as they progress in unhurried frames from Japan, to a plane, to the United States, only connect the visible characters tangentially to the words and action. We’re only shown people—including the main characters—from the back, in partial profile, or in glimpses of hands and arms, as in the top right frame below:

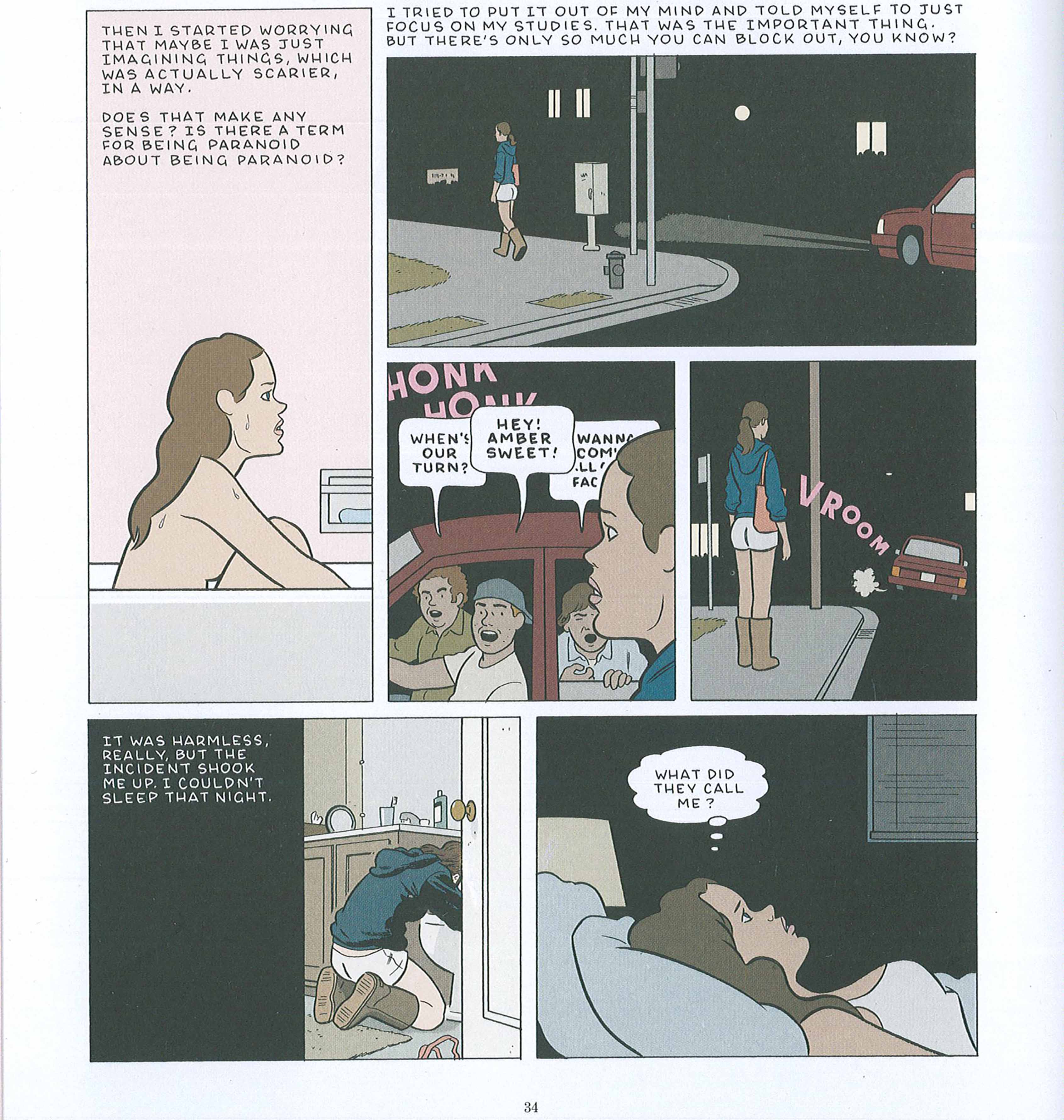

This piece most closely resembles Tomine’s work for his other main gig, as a cover artist for “The New Yorker.” His covers condense so much story into a single image, they serve as mini-screenplays. Yet his work never feels crowded—he instead plays with black space, blank space, and even pink, as in this excerpt from the story “Amber Sweet”:

Social media these days can feel like a happiness enforcer, with little gradation between its trolls and its blindingly sunny “perfect family” pics. Tomine represents an important form of witness not usually seen in comics these days—not to mention in culture more generally: a witness to real-life moments that don’t pirouette neatly into a satisfying close. As he told an interviewer for “The Guardian” in October 2015, “The goal, throughout this book, was to muddle people’s reactions intentionally rather than saying, ‘Here’s a funny uplifting story’ or ‘here’s a downer.’”

This commitment to realism makes this book hard to read at times, but it’s nonetheless beautiful and important. Like many parents with young children, I’m not naturally drawn to this kind of story right now. I’m often one of those annoyingly giddy parents who Tomine seems determined not to become. There was, however, a lonelier time in my life when such stories resonated with me, kept me company, and helped me keep my perspective on the world and my place in it, however small.

Wherever your life is right now—I hope it’s on the happier end of the spectrum—know that books like these will be here for you, for a future self who might need to know they’re not as alone as they think.