“Why Art?” by Eleanor Davis. Fantagraphics Books. February 2018. 200 pp. Paper, $14.99. Adult.

Thanks to Better World Books, 215 S. Main St. in Goshen, for providing me with books to review. You can find or order all of the books I review at the store.

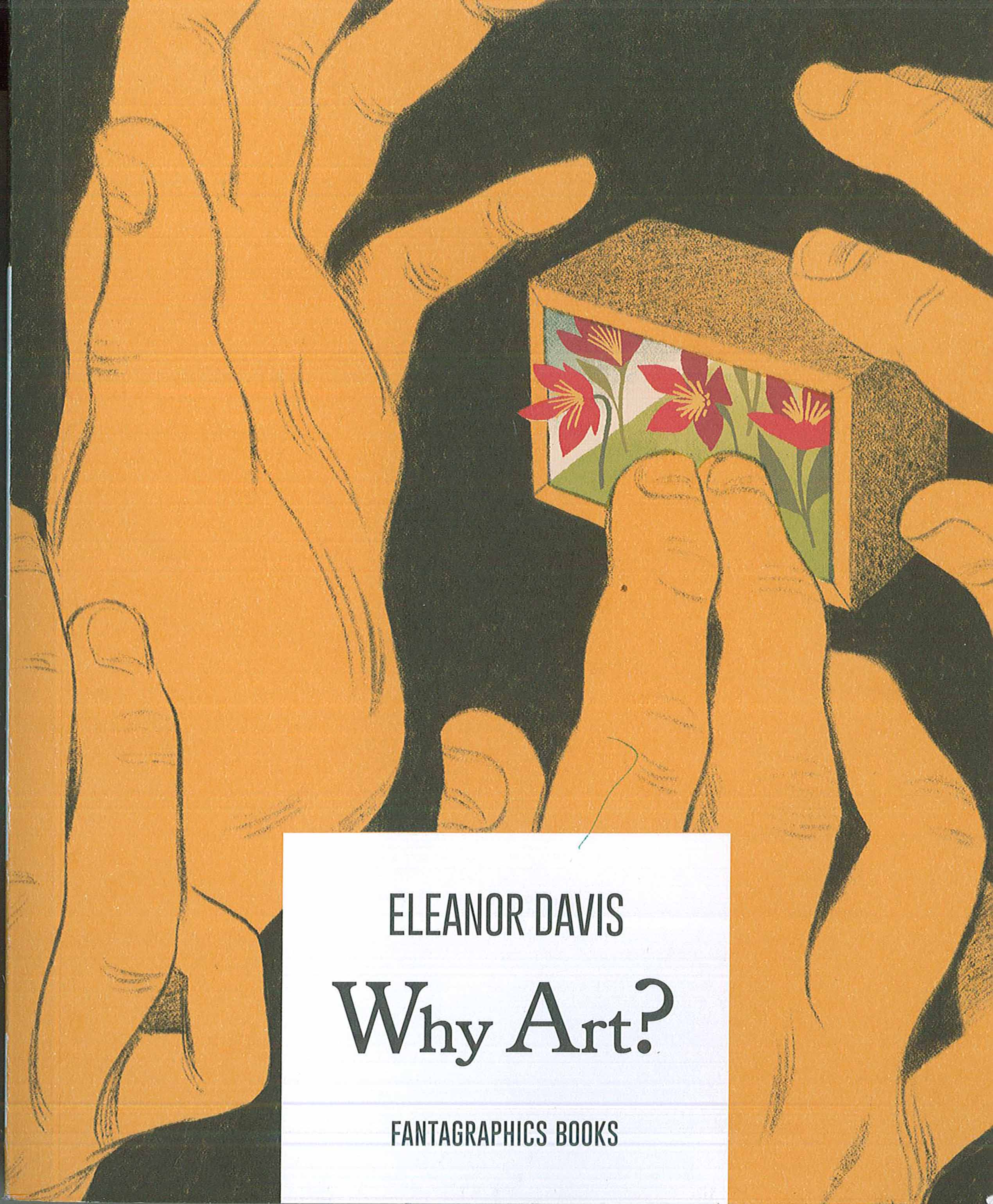

You could read this book in a flash. It’s short. It’s small. You could fold the almost life-sized hands on the cover into your own hands, then carry the book around with you, slipping it in and out of your bag as you enter and exit lines at the grocery store or the bank. I recommend that you read the book this way. Then I also recommend that you sit down with it and give it a second or third read, the time it deserves.

Illustrator and cartoonist Eleanor Davis is finally making a living on her art. Once you learn her style, you’ll see her all over the place. Check out her personal website, and you’ll see work that appeared in “The New York Times,” as well as “The New Yorker.” She’s designed Google doodles, and illustrations and posters for nonprofits like the Bronx Freedom Fund and musicians like Sylvan Esso and the Decemberists. She’s also well known for her work for kids and young adults: her 2008 TOON Book “Stinky” won her the first of many awards to come as her career progressed.

Perhaps to resist being pigeonholed, some of Davis’s recent work has been decidedly adult. “This is an 18 & over twitter! Rude jokes. Sex drawings,” she warns @squinkyelo. Yet some of her recent work for adults has also become gut-wrenchingly sweet. After she wrote “Love Story,” as she admitted to the “Women and Comics” blog, her husband and fellow artist Drew Weing had a hard time believing its sincerity: “He thought there was a catch, some secret bitterness or joke I’d hidden inside there. There wasn’t, though. It’s just a happy story about folks.”

“Why Art?” is neither “just a happy story,” nor “just about folks.” Very few titles posed as questions introduce a book that’s “just” anything: the question usually signals seriousness, as well as, readers hope, the intellectual complexity to back that seriousness up.

Yet although this book is plenty serious, it starts with a joke. Even more impressive is that Davis manages to slip her first joke onto the title page. No, this isn’t the book’s fourth edition—this isn’t even the type of book that would go into a fourth edition. And no, this isn’t the stuffy art history textbook which does tend to go into fourth, fifth, and sixth editions, and in which readers tend to hear really good questions like “Why art?” stifled by dry discourse and a self-important, condescending tone.

That said, I love flipping through old art history textbooks, and Davis must as well: this book showcases Davis’s breadth of knowledge of, and respect for, all sorts of art—literary as well as visual—at the same time that it implores its readers not to take the history of art, her own book about art, or themselves too seriously.

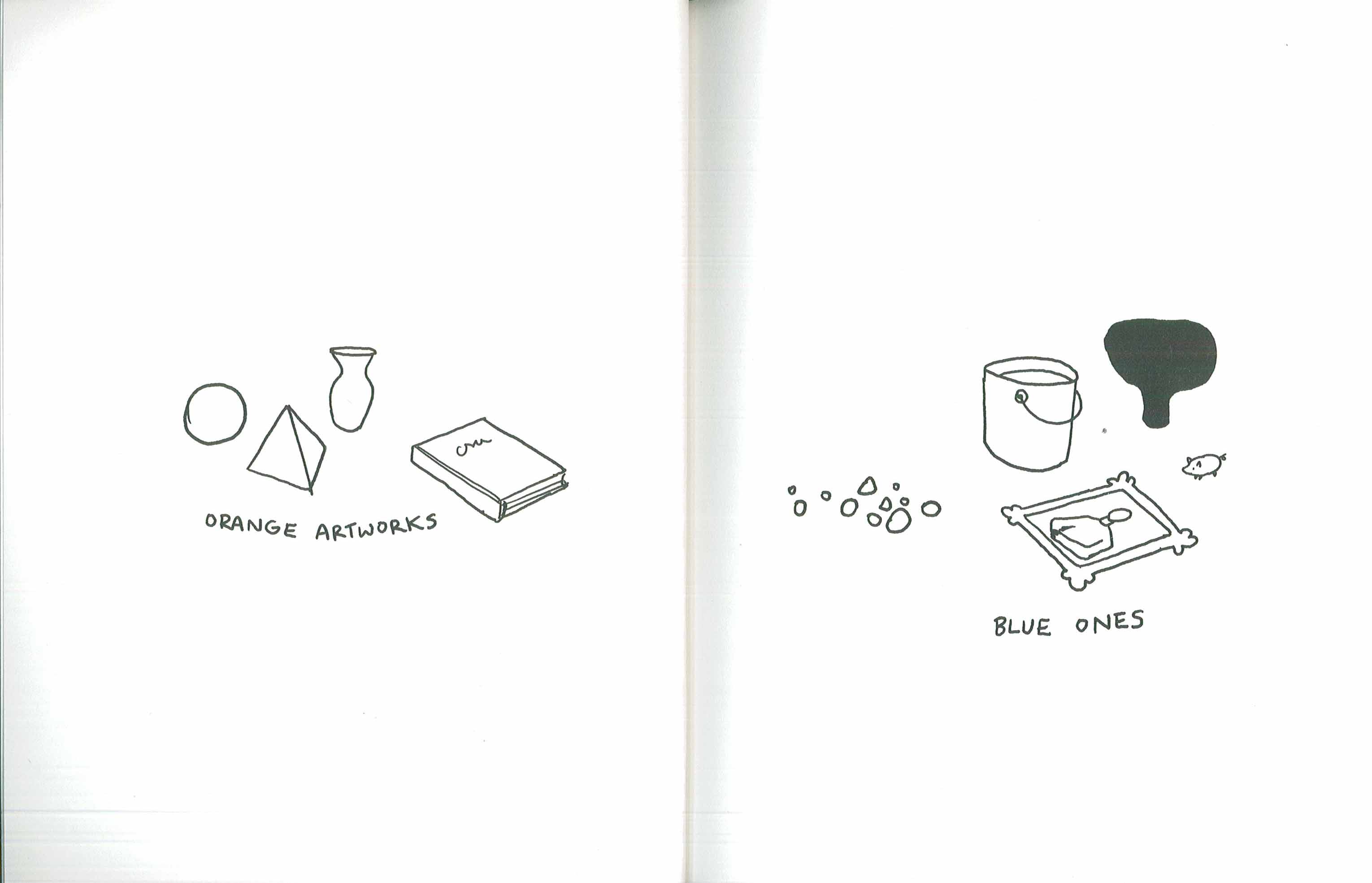

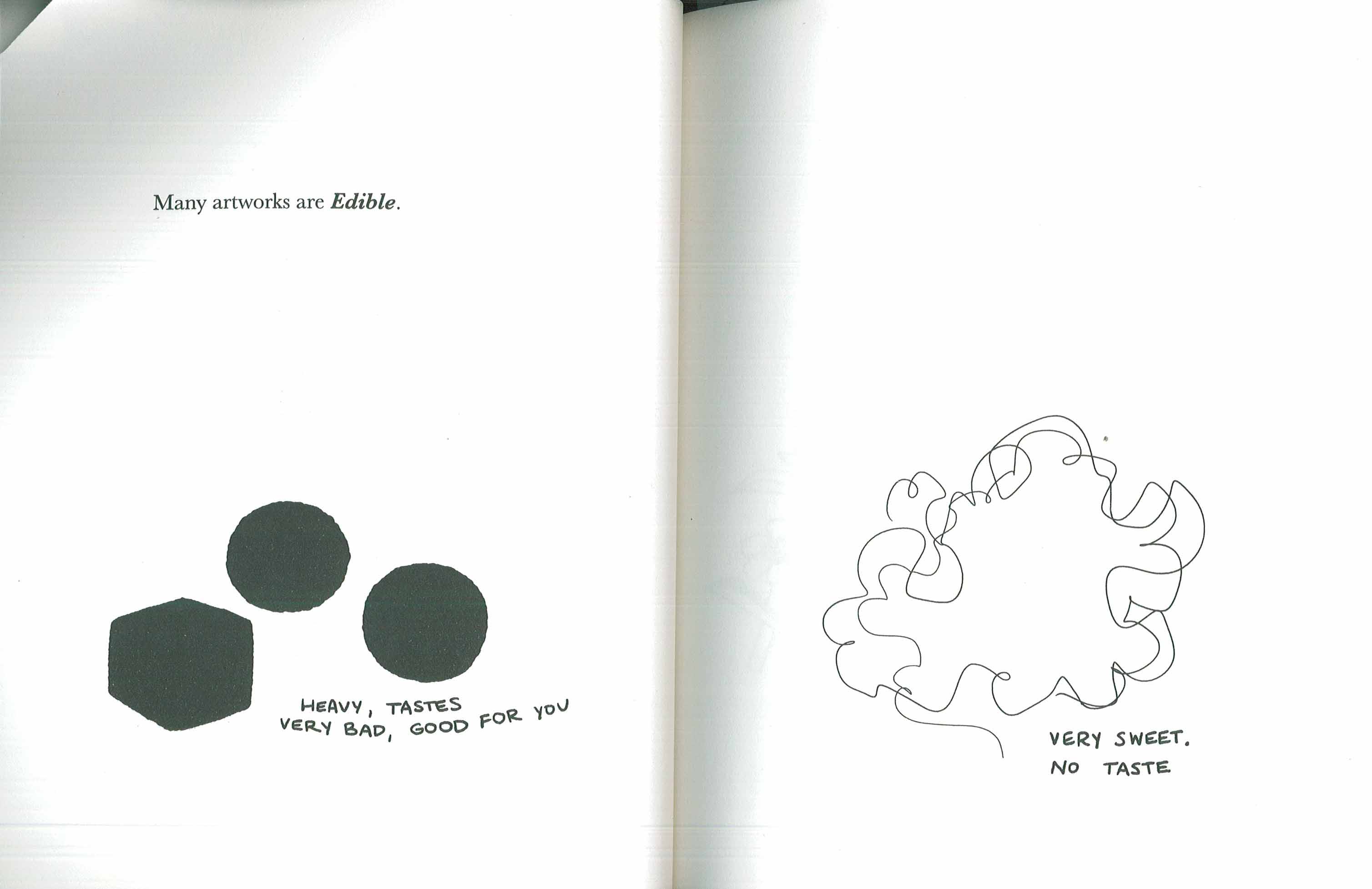

And the humor continues: just in case readers don’t get the title page joke, the book launches into its tongue-in-cheek analysis with the first and “most basic category of artwork”: color. But turn the page, and readers are met not only with black and white outlines—the absence of color—but also with outlines of “artworks” that might not correlate with the colors they’re supposed to be,

or might not even correlate with objects that tend to be defined as “art” in the first place. Like a bucket or a tiny figurine of a pig. An ostensibly blue pig, for that matter.

But the questions continue. Maybe Davis would have colored these pages in if she could have? Maybe her publisher didn’t want to spring for the expense of color printing, and Davis simply made the best of her budget?

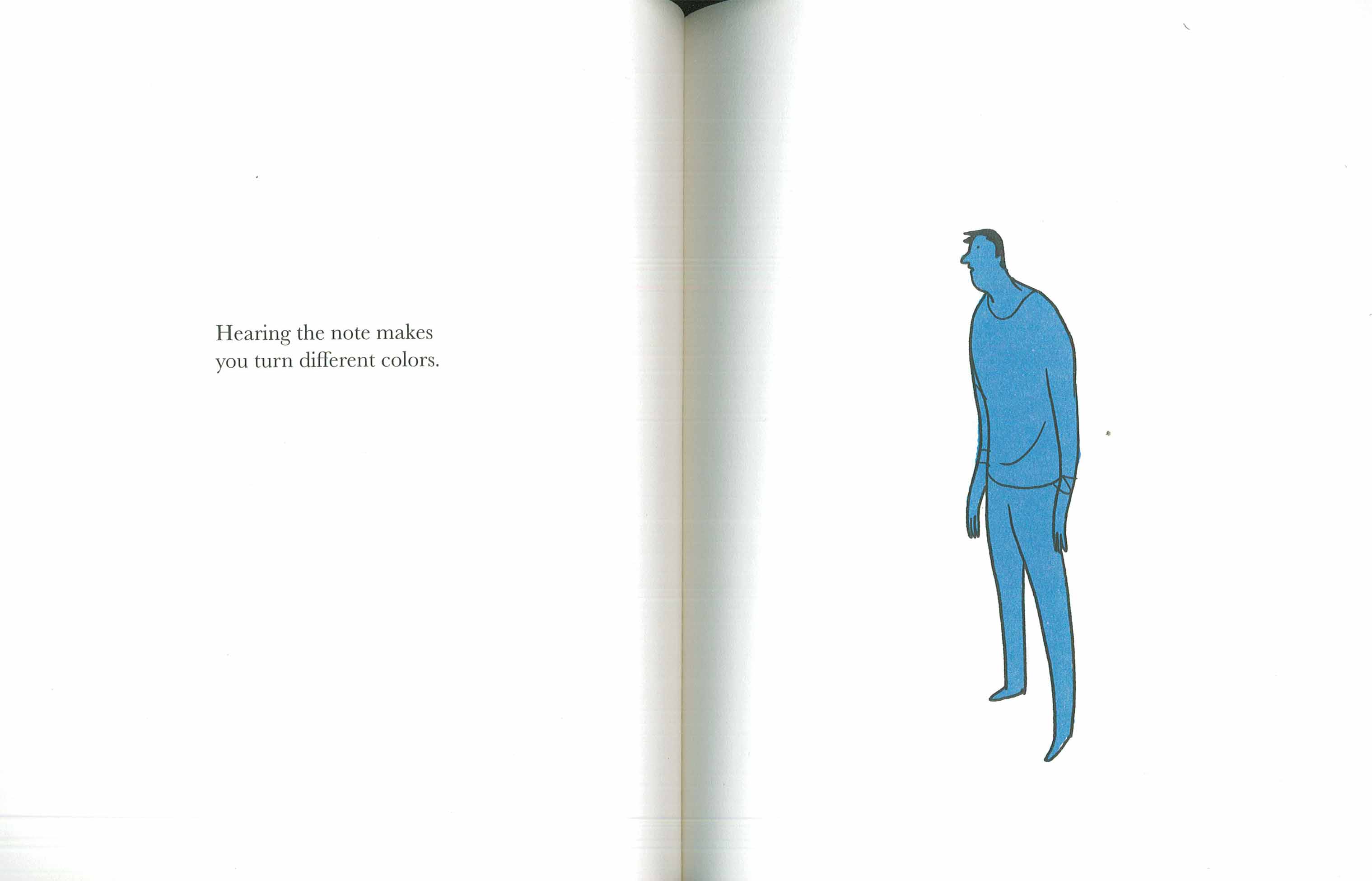

Almost halfway into the book, once you’ve just about forgotten the opening questions, the narrator introduces the work of an artist named Sophia. Sophia’s art comes with instructions for what to do “in case of an emergency”: shake her “talisman,” and you’ll hear a “little musical note,”

Turns out that Fantagraphics could afford color, because you see this guy turn magenta, then green—slowly, page by page.

Davis is messing with us. She could have used color earlier, but chose not to. She wanted to wake up your brain, to make sure you were paying attention. She wanted, in short, to make sure that you weren’t taking art for granted. In the process, you realize that neither should you take her for granted as an artist.

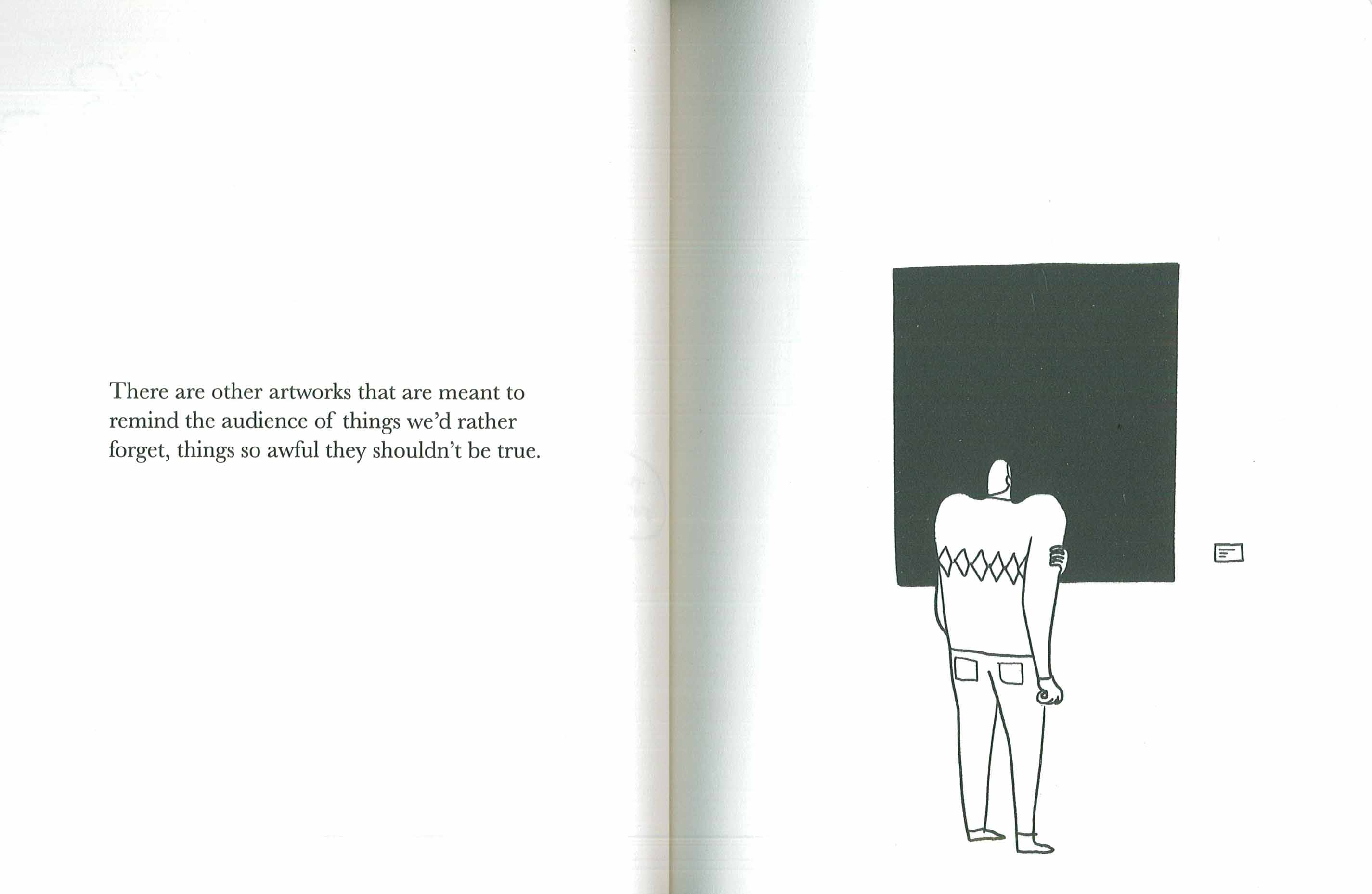

Consider this page from the first half of the book, for example:

Look at that hand on the guy’s right arm: not only is it awkward, but I’m pretty sure it’s not anatomically possible (especially that too-low elbow on his left side). Yet this small, intimate moment between art and viewer cuts to the heart of what art can do for us as individuals, and how deeply a picture can affect us—even, in this case, with a mere block of color, or depending on how you look at it, the absence of color.

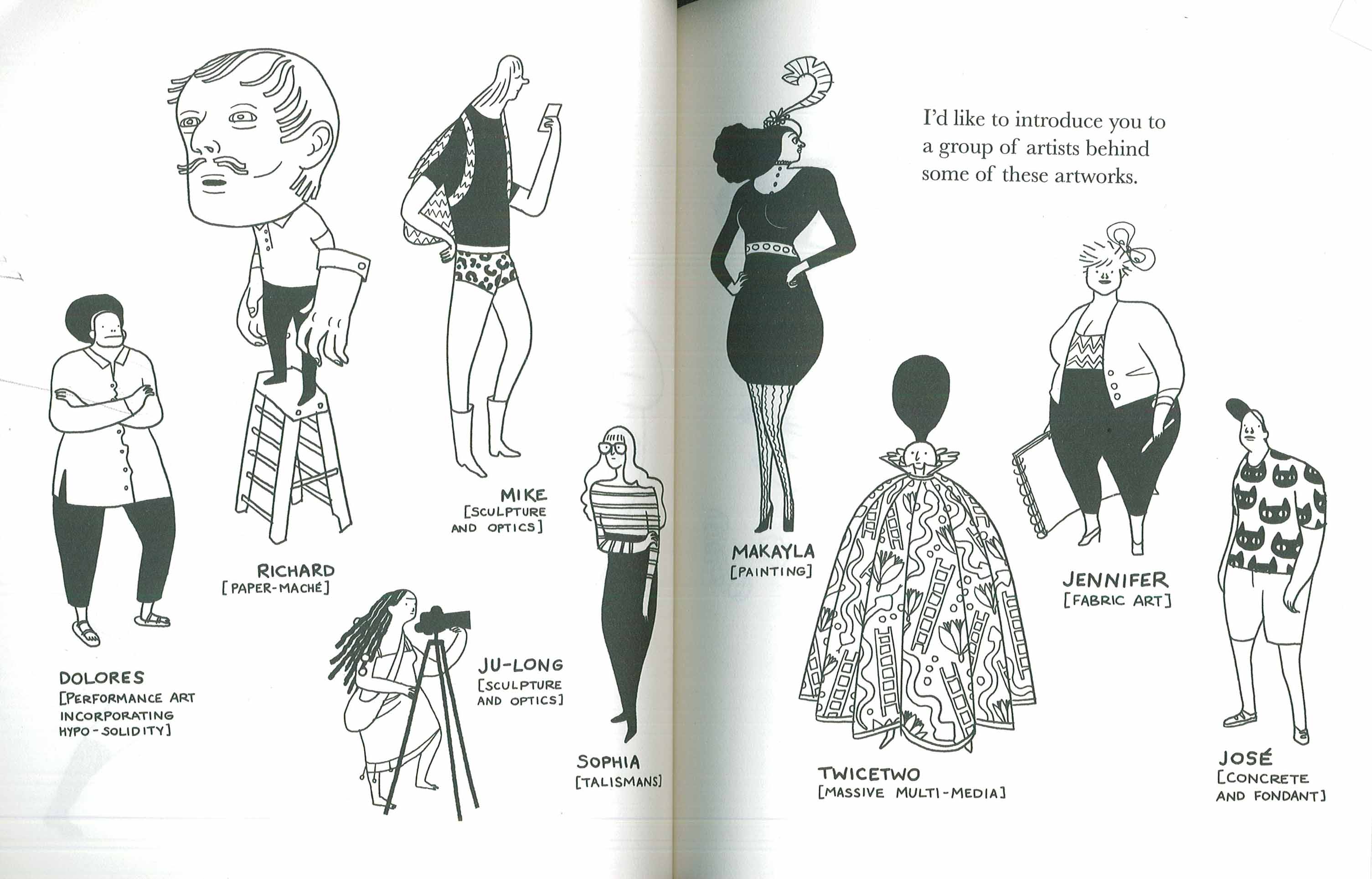

About halfway through, the book shifts from treatise to example: a story about artists learning, through their own experience, how to negotiate the relationship between self-expression and audience, between art as personal therapy and as societal commentary and communication. These are such huge questions, you might think Davis would need complex images to work through them. Yet her expert, simple lines pack a density of thought as well as a complexity of character. Here, for example, is her cast of characters:

As we move into story, the questions get bigger, not smaller. How does an artist live in a world often inhospitable to artistic expression? How does an artist balance her artistic expression not just with making meaning, but with survival?

This book ends with more questions than answers, which might not be to everyone’s taste,

but as a fan, I’m delighted to keep watching Davis figure out what needs to be said, and put her art into action. As she said on the “Women and Comics” blog cited above, “I want to think less, and do more. I want to be someone who leaps down onto the tracks. I hope I can learn. I’m studying hard.”