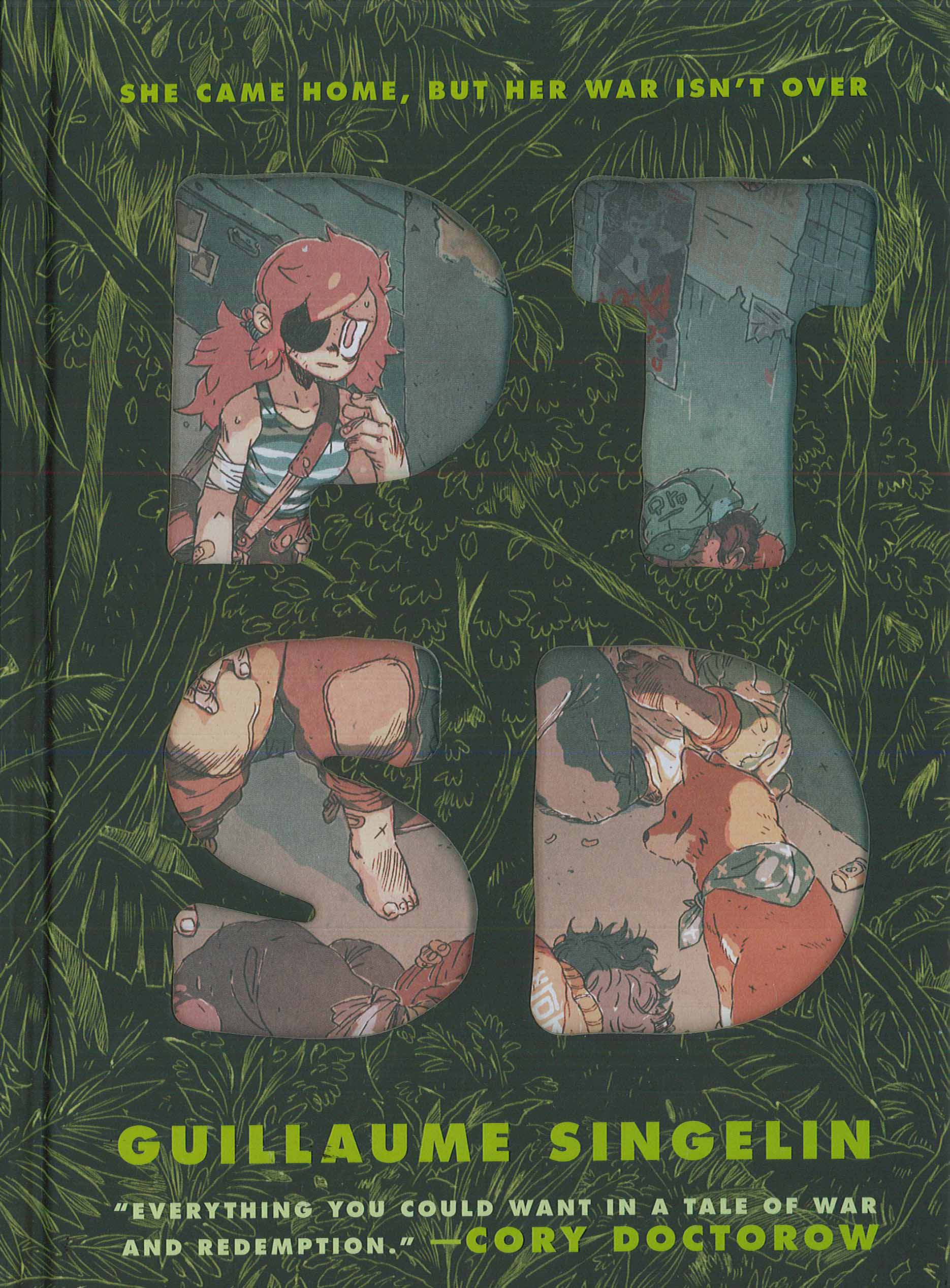

“PTSD,” by Guillaume Singelin. First Second, February 2019. 208 pp. Hardcover, $24.99. Adult, maybe older teen (some graphic violence).

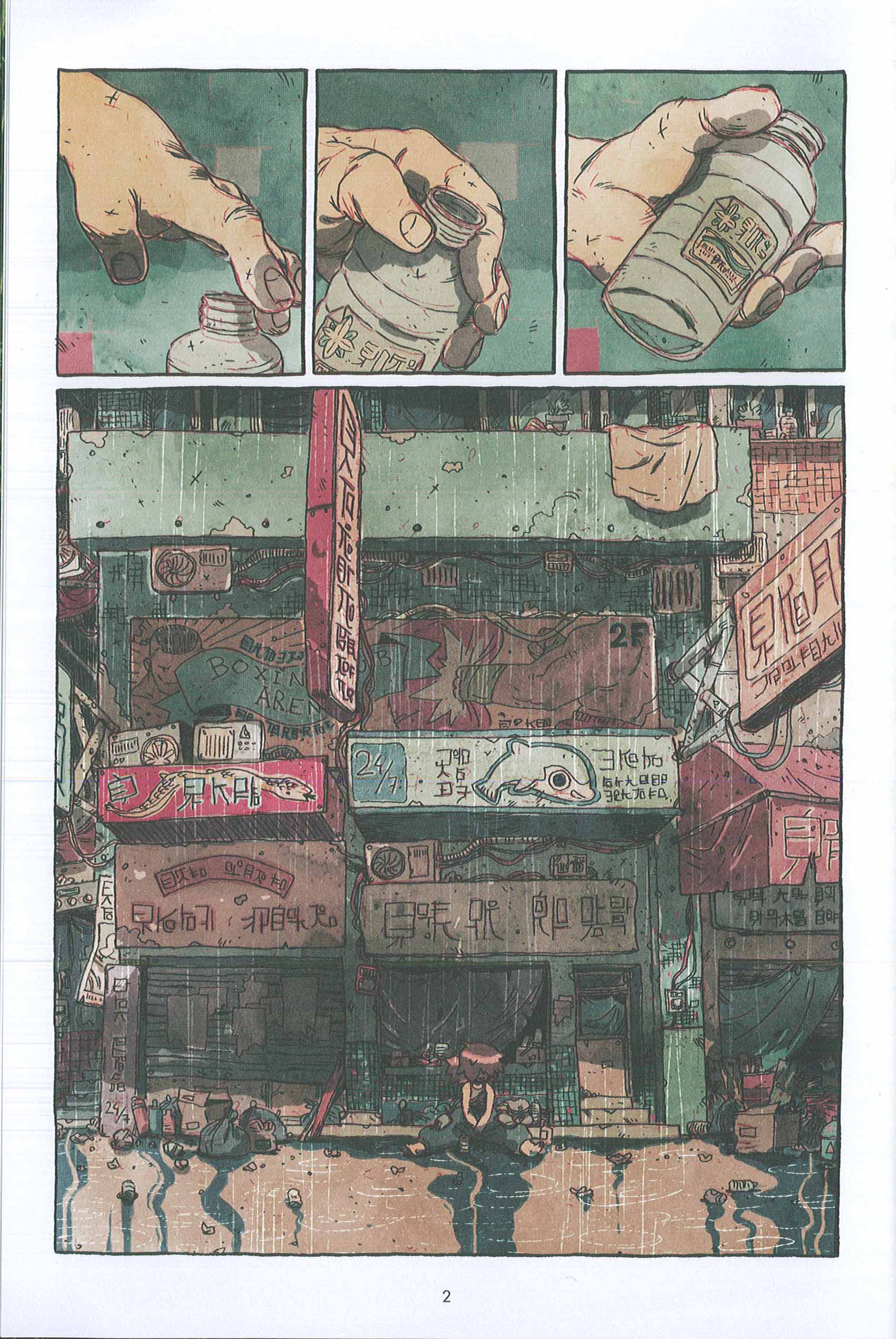

“PTSD” opens with the elements: wind, rain, cold and other forces beyond human control. A woman named Jun, striking for her red hair and eye patch, navigates a dark city teeming with sights, smells, sounds, and textures so rich as to be claustrophobic. A veteran, Jun spends much of the story struggling for control of her self, her life, and especially the addictions she’s been unable to shake since the war in which she served as a sharpshooter.

The war, the city, and Jun herself are all fictional, dreamed up by French-Laotian author and artist Guillaume Singelin. Well-grounded in reality, however, are the war’s continuing effects on Jun and her fellow veterans as they battle for survival on the streets. Like too many veterans worldwide, Jun and her friends have been abandoned by a government all too ready to send them to war, but ill-equipped to help them re-integrate into society when they return.

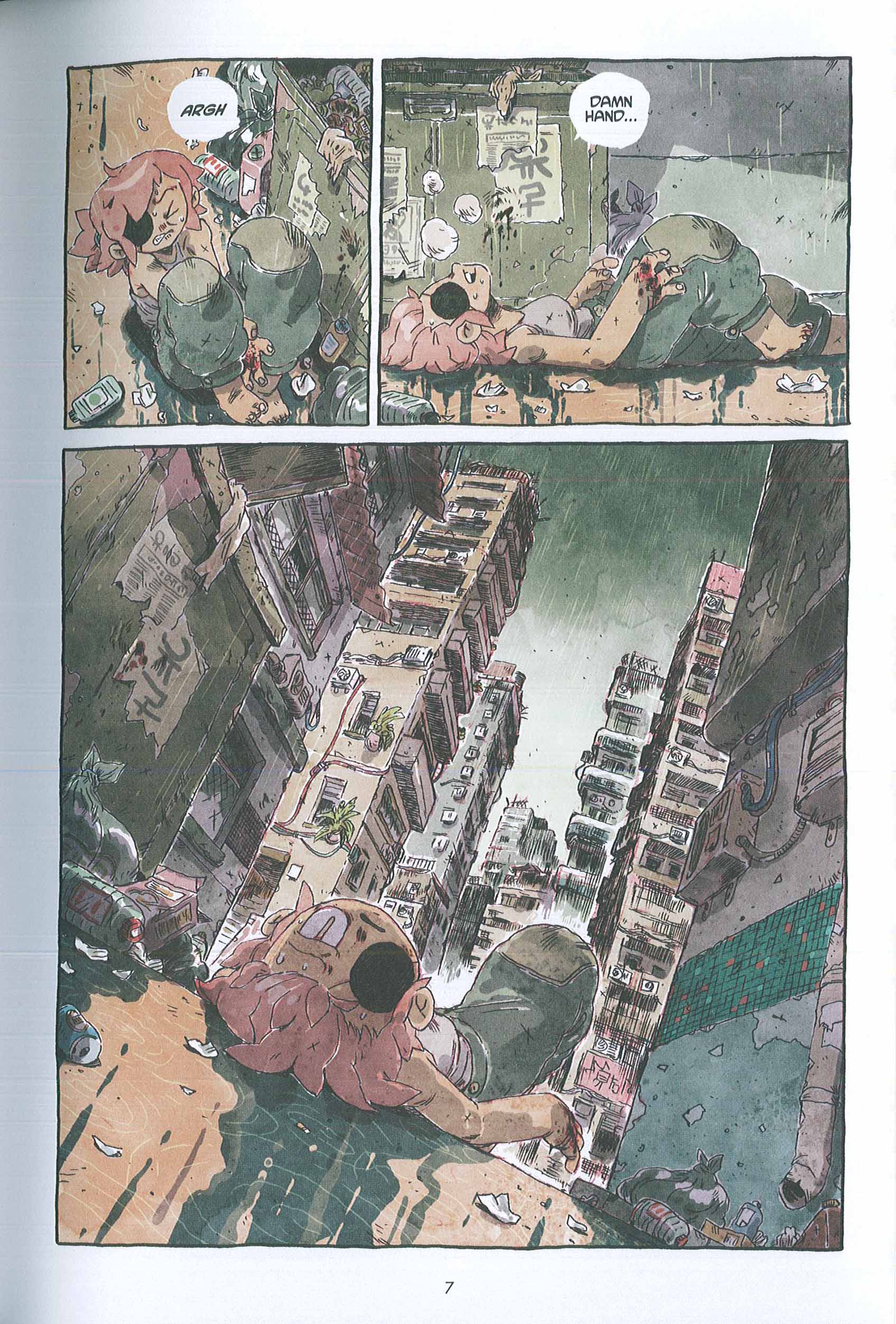

Mental illness is difficult to draw, and PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) is no exception. Jun’s trauma manifests in her external landscape as she struggles to reconcile her past with her present. Violence is all Jun has known in her adult life, so it’s understandable that her initial attempts to improve her and her fellow veterans’ situations are rooted in violence. The center of the story and the center of the book are both spattered with blood. This is not a tale for the squeamish.

The unsettling nature of this violence is heightened by Singelin’s cartoonish characters, who look more like escapees from a manga-inflected episode of “Sponge Bob” than characters from a war story like “Apocalypse Now.” Jun’s eyes are huge, and her hands and feet are meaty and hobbit-like, too big for the rest of her body.

Once readers become accustomed to such clashes, however, they serve to heighten the story’s cinematic sweep. In a postscript at the back of the book, Singelin cites a number of US film inspirations, from classics like “The Deer Hunter,” “Rambo,” and “Full Metal Jacket,” to more recent movies like “The Hurt Locker.”

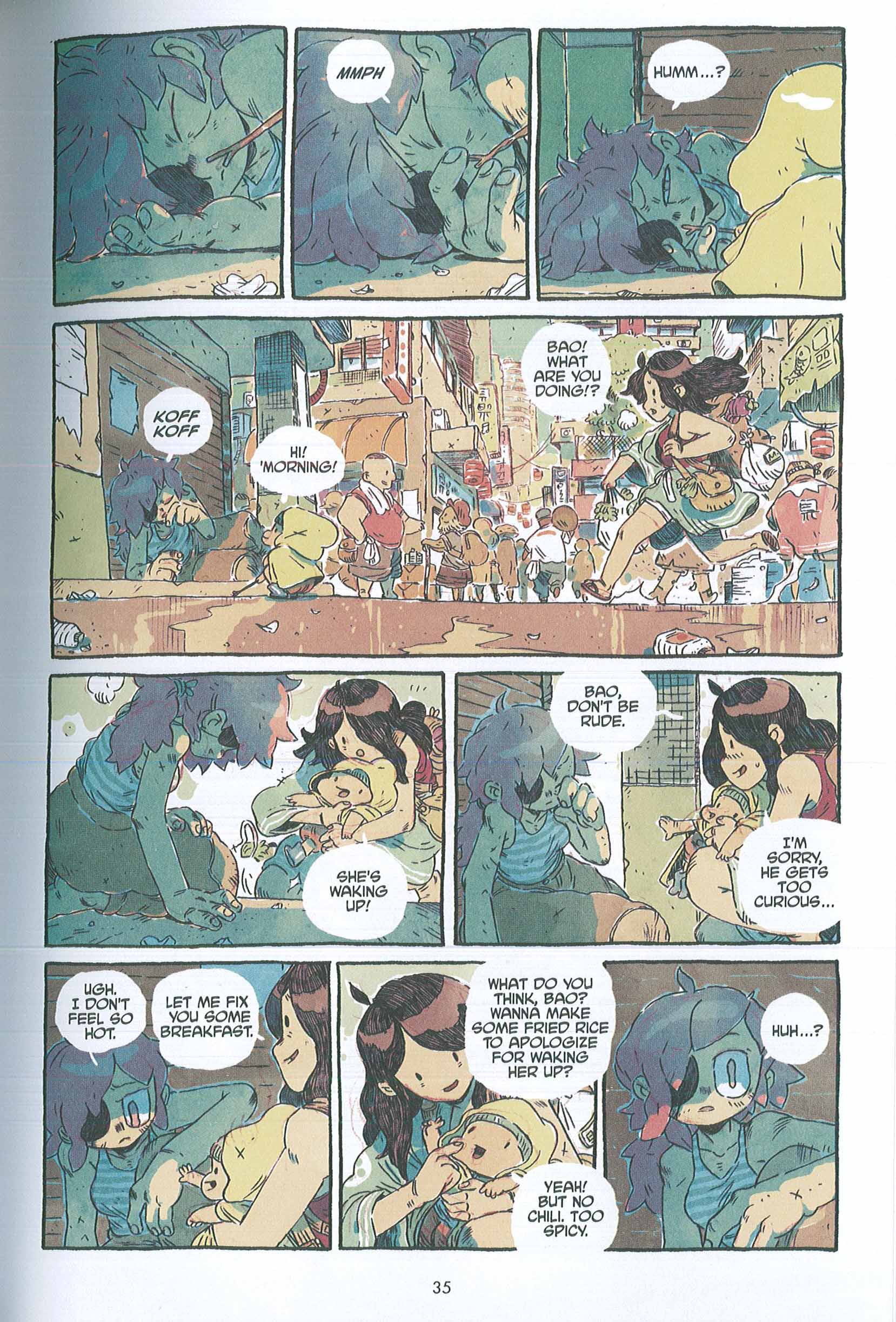

Singelin has illustrated many projects—a surprising amount for how young he is—but this is his first solo effort as both author and artist. He could use more practice with plot and character; dialogue and motivation in “PTSD” are oversimplified at times. Characters like restaurant owner Leona and her child Bao, for example, who attempt to befriend Jun, come across as too innocent.

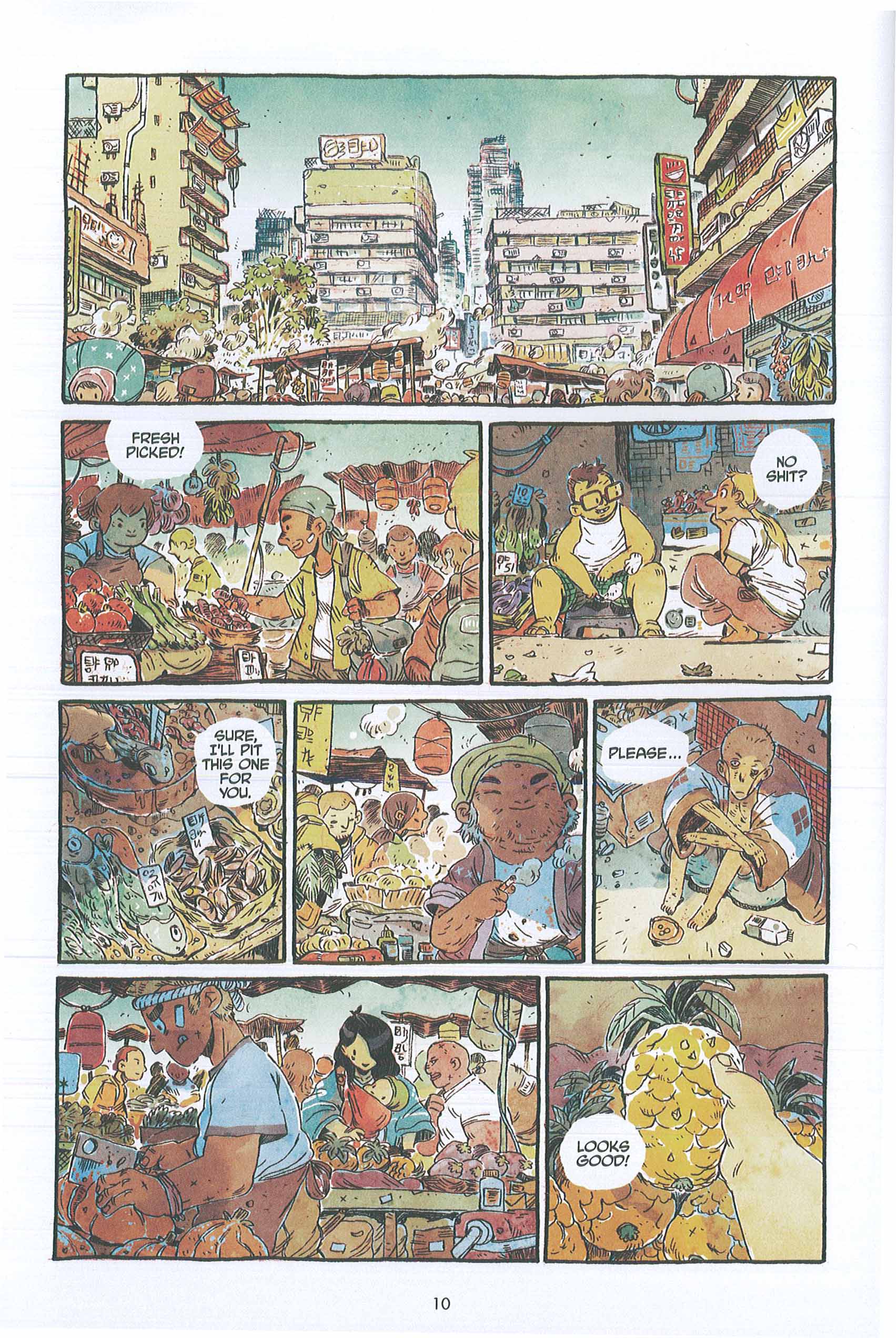

The visuals, however, are stunning and well worth your investment. Changes in color palettes signal scene shifts, from the gritty nightscape in which Jun struggles to survive,

to the daytime market that brightens the whole story in the flip of a page:

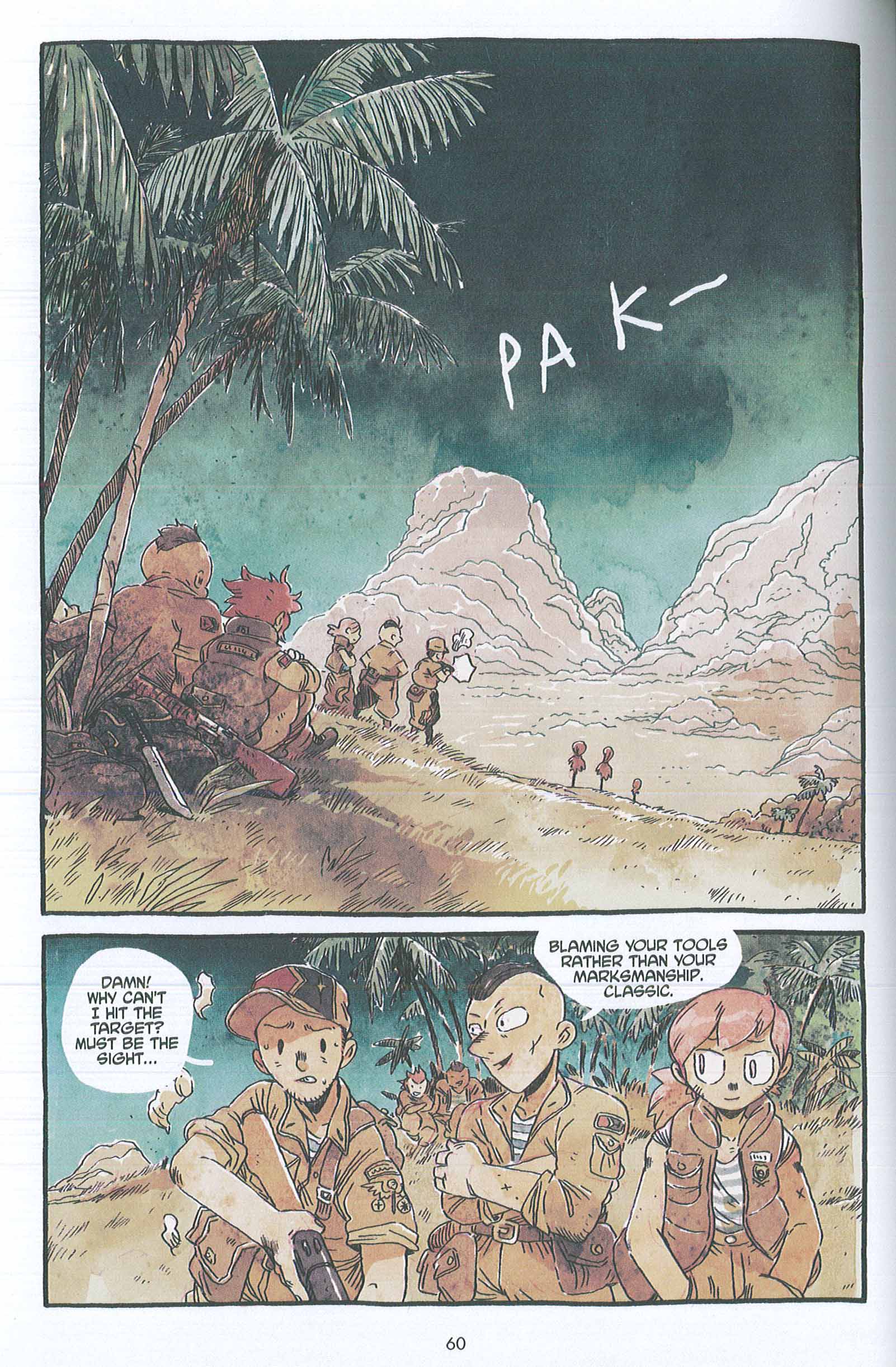

Even the landscape of Jun’s flashbacks proves surprisingly warm:

In moments like this, Singelin conveys how and why Jun misses the war—one of the realities of veterans’ lives that many civilians find difficult to understand. The book’s visual reinforcement of Jun’s emotional confusion helps illustrate and humanize the clash between Jun’s internal dissonance and an otherwise peaceful world.

The stylistic evolution of Singelin’s career is built on such dissonance. Leona’s child Bao, for example, looks like a baby but acts mature, like an adolescent in the body of an infant. The effect is, again, unsettling:

Compared with Singelin’s earlier work, however, the characters in “PTSD” look downright realistic. Especially notable are his wormlike yet weirdly cute characters for “The Grocery,” a French series written by Aurélien Ducoudray and illustrated by Singelin. Much as in “PTSD,” these surreal characters navigate dark, all-too-realistic landscapes.

Singelin is definitely an artist and creator to keep watching. You can follow him and his warped, sometimes gruesome, but ultimately compassionate world on Twitter (@guinoir) and Instagram (@blackysan). Singelin’s trippy characters making their way through gritty, intense content ultimately classifies his work as the best type of speculative fiction: fantastical enough to catch our attention, yet real enough not only to hold it, but to help us re-see a difficult world from a new, more thoughtful, and hopefully more productive angle.