Thanks to Fables Books, 215 South Main Street in downtown Goshen, Indiana, for providing Commons Comics with books to review. Visit the store or contact them at 574.534.1984 or fablesbooks@gmail.com to find or order any book reviewed on this blog.

”Rusty Brown, Part I” by Chris Ware. Pantheon, September 2019. 352 pp. Hardcover, $35. Adult.

“Sprawling” is an adjective frequently applied to the visual and narrative style of vaunted comics master Chris Ware. The above image is only a section of the unfolded cover of his new book, “Rusty Brown, Part One,” but it well conveys the nested, insular, and almost maddeningly complex narrative mapping for which Ware is famous. (See my review of his 2012 book in a box, “Building Stories.”)

“Depressing” is an adjective frequently—perhaps most frequently—applied to Ware’s characters and their stories. In “Rusty Brown,” however, though the characters’ lives are often bleak, the book culminates in an expression of the type of hope and determination that keep Ware’s characters—and, really, the human race—going, even in the face of despair. “Books can’t tell us how to live,” he explains in a recent ”Guardian” interview, “but they can help us get better at imagining how to live.”

As well as how not to live, as some of the characters in “Rusty Brown” suggest. The book runs one by one through the stories of seven protagonists, introduced at the start of the book with film-like credits. The names are all very similar: for example, “W.K. Brown as W.K. ‘Woody’ Brown.” All of the characters either teach at or attend a small private school in Omaha, Nebraska. Though the real-life Chris Ware is associated with Chicago—he lives in the suburb Oak Park, populated by Frank Lloyd Wright buildings and patterns that echo throughout his work—he grew up in Omaha. “Rusty Brown” could be an alternate, “what if?” universe for Ware, especially since an art teacher at the school shares his name.

Some of these stories have been previously published in full or in part, usually in periodicals that carry Ware’s series “Acme Novelty Library,” like Chicago’s “New City” or the “Chicago Reader” (where Ware first blew my own college-aged mind in the 1990s). Sections have also appeared in newspapers like the “New York Times” and London’s the “Guardian,” and the first section of the story of the character Jordan Lint was first published in Zadie Smith’s anthology, “Book of Other People.”

Lint, the character at the book’s core, is the only one whose life we follow from birth to death. Lint is also the book’s bleakest character, his poor choices escalating from cringe-worthy to downright appalling. He experiences only brief flashes of hope, which he habitually squanders.

Lint is an appropriate name for this dark character. In the interest of realism, Ware makes a point of marring almost every carpet in this book—a funeral home is the only exception—with lint and other real-life debris that could easily be vacuumed up. Similarly, this mostly despicable, selfish bully, doesn’t make much of a mark, and has a tendency to downgrade rather than improve his surroundings.

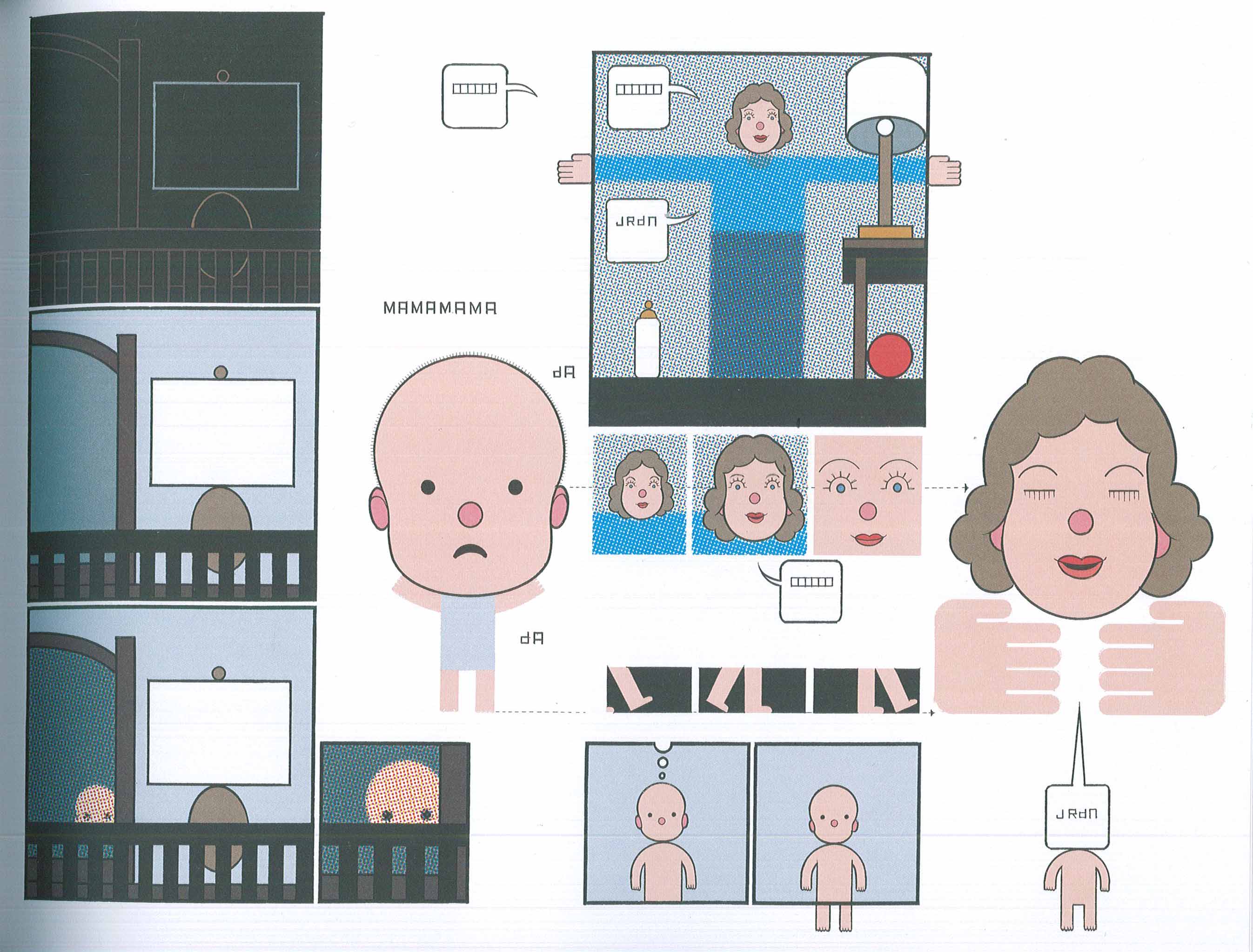

So why spend your energy reading about a character like Lint? As Ware explains to “Publisher’s Weekly,” “I’ve tried to imagine people different from myself and also to understand and empathize with them as much as possible, since I believe that’s really the only aim and hope for humanity and art—and also one of the points of the book, more or less.” In the interest of making sense of this generally mean person, Ware starts as early as he can, putting readers into Jordan’s crib with him as he tries to make sense of his mother, his language, and the rest of the world:

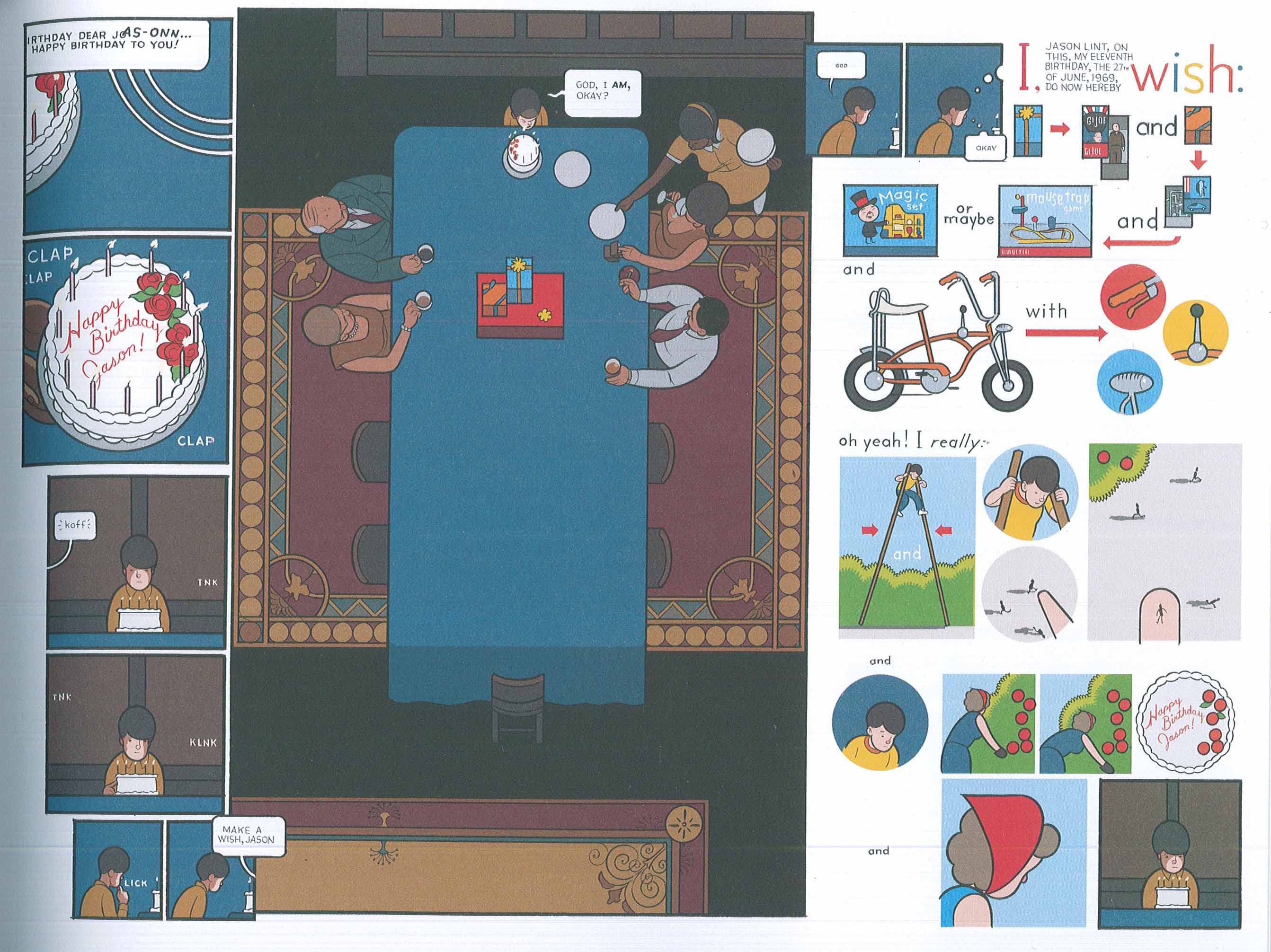

The images grow in complexity as Jordan’s understanding of his traumatic world—his dad’s abuse of his mother, his mother’s early death—develops. Here’s 11-year-old Jordan:

Right as Jordan realizes that the things he can’t have—the resurrection of an ant he once squashed by mistake, and of course the resurrection of his mother—are the things he most wants, we also witness his name changing to his “character” name Jason (see the rewritten lettering in the top left word bubble).

Jordan/Jason’s life continues downhill from here, except for a briefly happy marriage (the only other time when his name returns briefly to Jordan), which he manages to ruin by falling back into self-destructive habits. This character’s death is artistically and brilliantly rendered, but ultimately exemplifies that Shakespearean/Faulknerian “sound and fury, / Signifying nothing.”

Lint’s life is sandwiched between shorter glimpses of other characters’ lives, including the minor character of Ware himself. Ware doesn’t protect himself as a character: “Mr. Ware” not only cavorts with Lint in his teenage stoner phase, but makes fun of one of his colleagues, and fantasizes about one of his female high school students. When asked in the “Guardian” interview how autobiographical his character is, Ware jokes, “Well, I needed a jerk and I was available.”

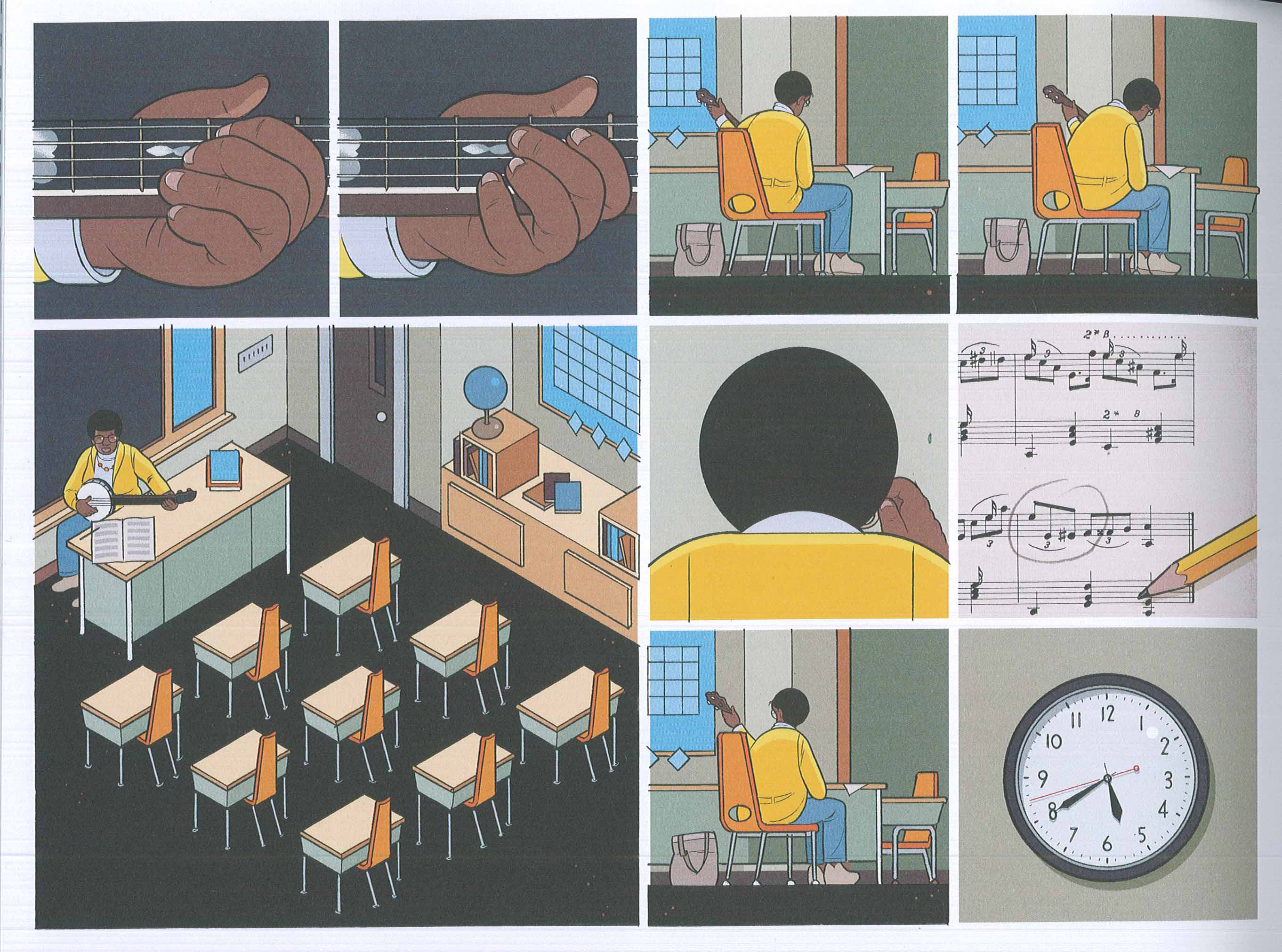

The last time we see Ware the character in this book, however, he redeems himself, if only mildly, as the only colleague who comes to the evening “banjo party” of his fellow teacher, Joanne Cole. The book closes with Cole’s story, which—as you might be able to guess from her awkward two-person party—is often sad and difficult, shot through with her lived experience of racism piled on top of the standard slings, arrows, and indignities faced by Ware’s other characters.

Visually, however, Cole’s story is beautiful and calmly brilliant. In these two pages, for example, note the way that Cole’s school (far bottom right) echoes the fretboard and body of her banjo, the hobby and creative outlet that seems most to keep her alive:

Cole’s dedication, perseverance, and lived injustice cohere into a quiet symphony in these two bright, slow, simple pages. Ware’s representations of the complex and powerful workings of history and memory on our identities and our very existence pack a powerful and disorienting punch that I’ve witnessed in no other artist; Lynda Barry’s collages in “What It Is,” which seem to bubble up from the collective unconscious, perhaps come the closest.

Experimental art is often a purely intellectual endeavor, pushing its readers away and into their own heads as they work to make sense of it. But Chris Ware creates the rare type of art that both works your brain and sucks you into the story. I swear I could hear the gears in my head churning as I read “Rusty Brown”—but I was also so wrapped up in these characters’ histories, memories, and immediate challenges, that the rest of the world fell away.

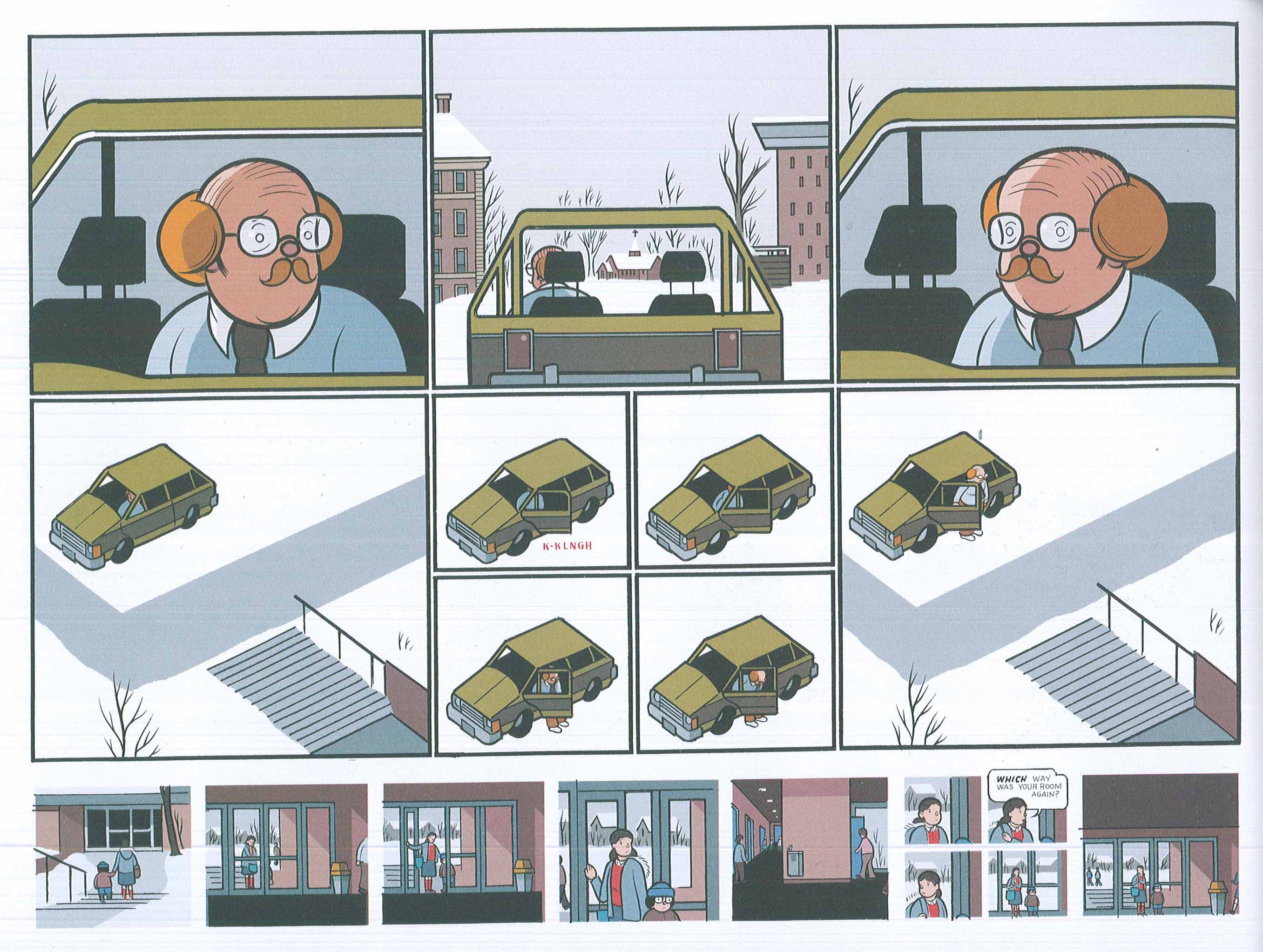

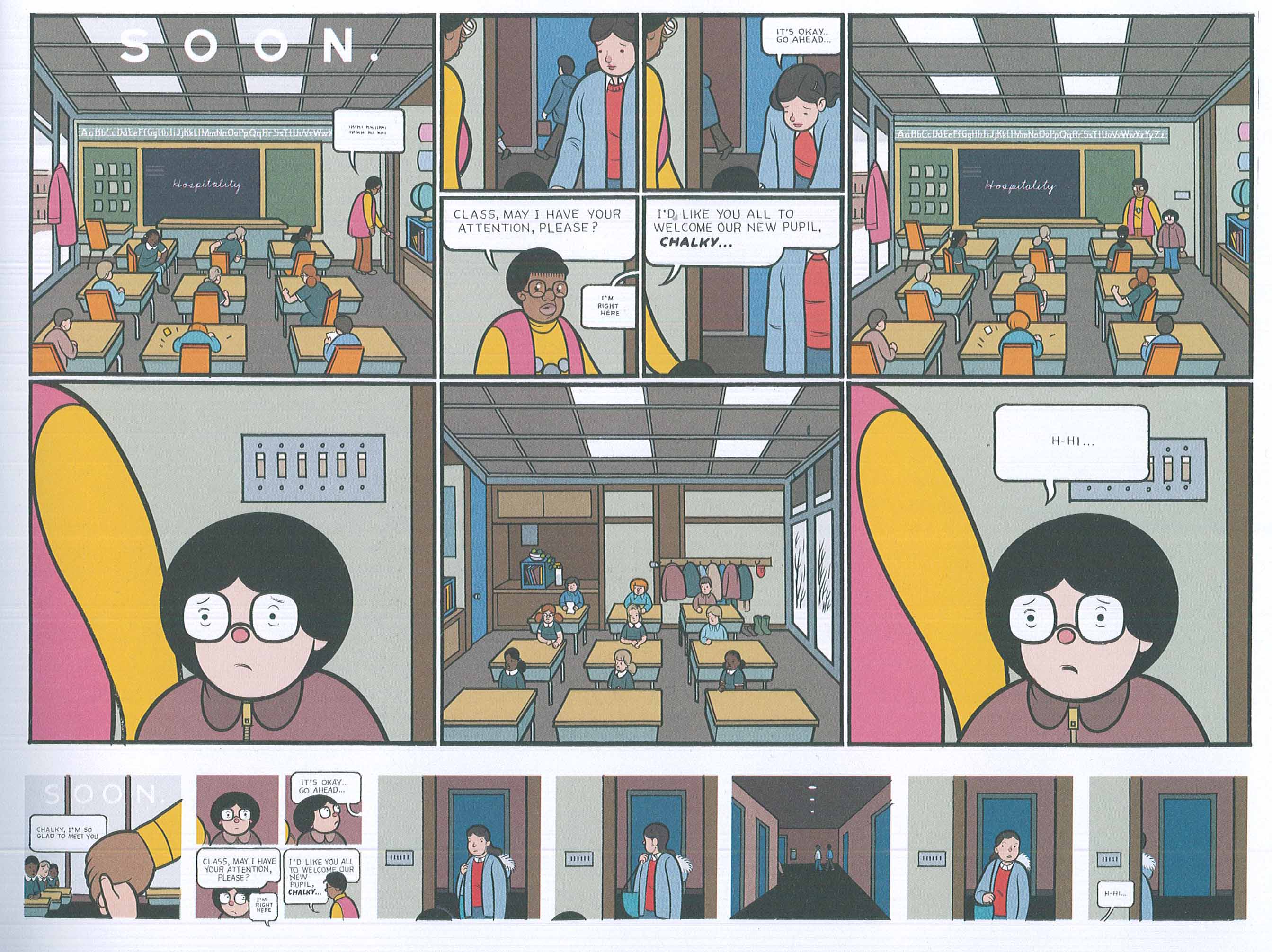

As an example of this wholly engaging complexity, Ware throws his readers two narratives at once right at the start of the book. The morning routine of teacher “Woody” Brown and his son Rusty take up most of the page, while Alice White and her much younger brother Chalky, who just moved to town, run like a filmstrip along the bottom. All four characters wake up, clean up, and eat breakfast in their separate houses, then head for their cars to drive to school—not terribly exciting, right? But Ware is such a narrative master that he cuts right to the heart of the anguish in each of their lives, so that despite the slow pace of these scenes, it feels like the peak of action flick adrenaline when the two stories briefly intersect, Chalky entering the same classroom as Rusty:

Ware always keeps a simultaneous narrative running in some form, sometimes with two intersecting stories like these, but most often within a character’s head: a mental historical commentary or a psychological subnarrative that can help make sense of inexplicable and/or negative actions. As he tells the “Guardian,” “I genuinely believe there’s a redeeming impulse of goodness in everyone, which is heightened by sympathy, if not by art, and in my own mind the two should be synonymous as much as is possible.”

Each of the characters in “Rusty Brown,” no matter how honorable (Cole) or despicable (Lint), harbors a deep history, and sometimes a rich interior life as well—which has led many critics to compare Ware to James Joyce, William Faulkner, and Virginia Woolf because of their literary modernist “stream of consciousness” narrative style. In terms of philosophy and visual complexity, however, Ware’s work most resembles the short plays of Samuel Beckett, which dissect and reveal the sad beauty within humans’ slow, lifelong patterns of habit and perseverance.

Much like all of the above-mentioned groundbreaking authors, Ware’s experimental style is often questioned, attacked especially because of its genre. At one point, the new student Alice White says to Woody Brown, “I hardly think that ‘science fiction’ could be considered a viable form of literature . . . genre fiction, maybe, but not literature.” Little does she know that Brown’s secret pride is to have published a science fiction story—most of which we get to read in a lovely though disturbing interlude, which Ware renders in deep oranges and blues. Science fiction, comics, banjos—all have been historically disparaged as “low” art. This stunning book, however, alternately exhausting and invigorating, crushing and hopeful, proves that to make and define great and important art, the genre matters much less than the honesty, intelligence, and commitment of the artist.