Originally published on GoshenCommons.org November 25, 2013

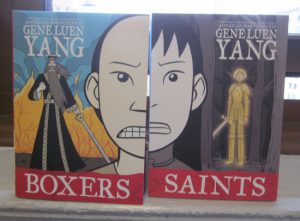

Last post I reviewed “March,” a history of the civil rights movement told from the perspective of congressman John Lewis. Most valuable about that book was the specificity of its history—how it re-told a story that most of us thought we knew. Gene Luen Yang’s paired books “Boxers” and “Saints” are also historical fiction, and similarly rewarding, but for slightly different reasons.

Like many North Americans, I’m fuzzy on the history of the Boxer Rebellion, but now that I’ve read these paired books, I can get pictures like these out of my head when I hear the phrase

and replace them with this:

(Thanks espn.com for—well, you can guess which one of the above three photos.)

“Boxers” and “Saints” are a rich, complex education in a chapter of Chinese, British, and world history not terribly well known in the US. In a recent interview in the “LA Times,” Yang says that he began researching these books in 2000, when a list of Chinese citizens who died in the Rebellion were canonized by the Catholic Church. Luen Yang grew up American Catholic, so many people he knew were excited about what they saw as long overdue recognition. But Yang explains that as he began to research the Rebellion, “The more I read, the more ambivalent I felt. Did I side more with the Boxers or their Chinese Christian enemies?”

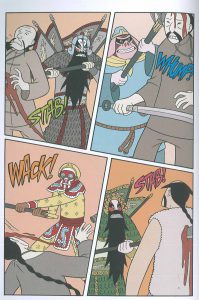

“Boxers,” the longer of the two books, tells the story of Little Bao, a leader of the Disciples of the Righteous and Harmonious Fist (or what the British colonialists called the “Boxers”), a roving group of Chinese revolutionaries who believed their powers so well-honed and “righteous” that foreigners’ guns couldn’t hurt them. Yang tells the story so well, you’re likely to believe in these superhuman powers right along with the story’s protagonists:

(Thanks to the “LA Times” for the second image.)

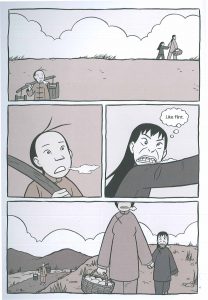

“Saints,” shorter, and printed with fewer colors, is told from the perspective of Four-Girl. Rejected by her family, she later takes the name Vibiana when she becomes a Christian convert. Vibiana believes she’s destined to be the Chinese Joan of Arc, but doesn’t discover Joan’s gruesome end until too late.

Like Yang’s National Book Award finalist “American Born Chinese,” “Boxers and Saints” is classified as Young Adult, but don’t let that label give you the impression that these stories are simple. Yang’s expert integration of storylines is not only mature but complex, and as with the best historical fiction, readers come away not only with new knowledge, but with knowledge that leads to more questions than answers.

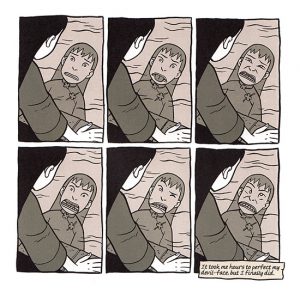

Most brilliant is the staggered overlap between the two books. The best example is the first of two scenes in which the protagonists from the two books meet. The top scene is from “Boxers,” the bottom scene from “Saints”:

When they meet again toward the end of each book, Little Bao discovers—as you might guess from the above images—that although he’s been carrying a torch for Vibiana his whole life, she barely noticed him at the time, and certainly doesn’t remember him. Their connection is crucial, however, especially because it is Little Bao, rather than Vibiana, whose narration finishes “Saints”—but since so much of the joy of reading these books is in uncovering the books’ retold and echoed narratives on your own, I’ll refrain from overexplaining on this front.

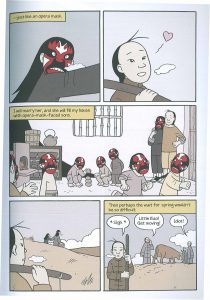

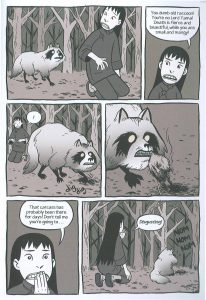

First Second, the books’ publisher, summarizes the linked stories perfectly as a “portrait of a descent into extremism”: what binds these characters on opposite sides of the conflict is how rejection in their youth led to unyielding passion as adults. Yet both books, despite their heavy history, revel in humor. Take this scene in which Vibiana—still Four Girl in this scene—first encounters “Lord Yama,” the demon who leads her to renounce traditional Chinese religion:

That “nom nom nom” in the background is subtle but hilarious in its precision—somehow “chomp chomp chomp” wouldn’t have been as funny. Most of the humor is likewise subtle yet precise. Another example is the “devil face” that Four Girl settles on when she decides to accept and revel in her outsider status:

(Thanks to patheos.com for the image)

“I hope the books encourage readers to look at both sides of every argument,” says Yang in his LA Times interview. “I also hope it encourages them to think carefully about the relationship between cultures, not just the ways they clash but also the ways they overlap.” I’ve long thought that humor is underestimated as a means to compassion and deeper understanding. In “Boxers and Saints,” Yang helps readers both laugh and cry their way to a more complicated understanding of a difficult history.

My next scheduled post is two days before Christmas, so what better review than two drastically different books about Jesus from this past year: “Punk Rock Jesus” by Sean Murphy and “Radical Jesus: A Graphic History of Faith,” edited by Paul Buhle. If you can’t wait to get into the Christmas spirit—from a comics perspective—you can order them from Better World Books in Goshen, Indiana.