Originally published on GoshenCommons.org February 3, 2014

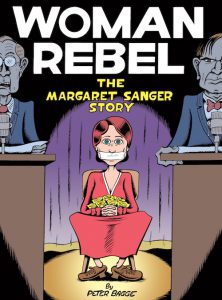

If you’re not familiar with Peter Bagge, he’s best known for comics about suburban youth with titles like “Hate,” “Apocalypse Nerd” and “Everybody Is Stupid Except for Me.”

Here’s a self-portrait that captures his damp, bug-eyed style as well as his chronically ironic tone:

Image from reason.com

If you’re not familiar with Margaret Sanger, originally trained as a nurse, she found her passion as a writer and birth-control activist in the early 20th century after she had treated countless poor urban mothers who, sick and exhausted, begged her to help them stop having children.

Image from biography.com

When I heard that Bagge’s most recent book was a biography of Margaret Sanger, Bagge could have illustrated my reaction pretty effectively: Huh??!!

As Bagge explains in the afterword to this meticulously researched book, his main motivation for taking on a biography of Sanger was the contradictions in online accounts of her history. “She was an effective practitioner of civil disobedience and passive resistance” (74), he writes, yet type her name into a Google search, and most of what comes up calls her “a racist; a genocidal maniac; a member of the KKK; both a fascist and a communist (sometimes in the same sentence); and my favorite, the inventor of abortion” (75). Bagge did his own research into primary sources, putting Sanger’s quotes back into historical context and even digging up original versions of photos that now appear on the Web in doctored form.

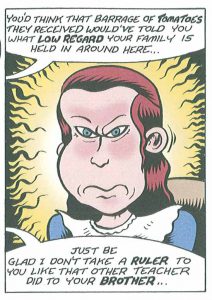

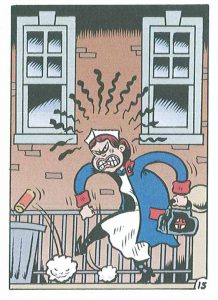

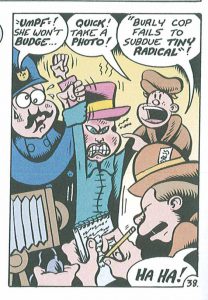

But Bagge’s motivation wasn’t merely to set the record straight. Bagge explains that Sanger’s life was so long, complex and “literally action-packed that all I could think of was ‘comic book!’ whenever I read of her exploits” (75). Perhaps even more than the demonstrations, raids and arrests, however, Bagge was drawn by Sanger’s fiery spirit, which angered pretty much everyone at some point: enemies, family, friends and benefactors. And she spent a good deal of time fuming, too. Here’s a short visual history of Sanger’s standard reaction to insult, illogic and injustice:

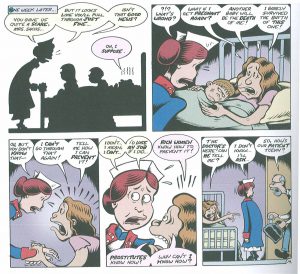

Bagge’s version of Sanger’s story addresses a lot more complication and nuance than these single frames convey, however. That middle frame, for instance, is her response after visiting the mother depicted below, who was on the verge of death the last time Sanger visited:

Not only does the doctor refuse on legal grounds to pass on any information—it wasn’t until the 1960s that the Supreme Court officially declared the Comstock Laws, which limited sales and “promotion” of contraceptives, unconstitutional—but he insults and blames the woman, saying that she should send her husband to sleep on the roof if she wants to stop having children.

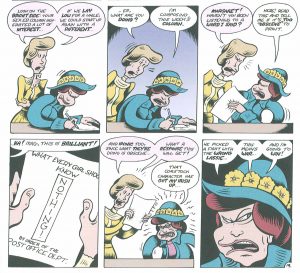

Sanger quickly tires of the self-righteousness and illogic of birth control gag rules. It was the post office at the time that determined what was too “indecent” to travel through U.S. mail, so when Sanger’s sex-ed column for the “New York Call” is censored, she revises the copy:

Sanger does, arguably, “win” in the long run by getting her information out, but Bagge doesn’t paper over the mistakes and uglier moments of her life history. Sanger’s belief that every woman deserves the right to make her own decisions about her reproduction drew her to every women’s group from which she could muster an audience, including Ku Klux Klan members. Rather than shrinking from this controversial moment in Sanger’s history, Bagge illustrates in a single frame why Sanger agreed to speak to an audience whose views she found distasteful: one of the audience members raises her hand early in the talk to ask Sanger to clarify her “terminology,” which is no more complicated than the word “vagina.”

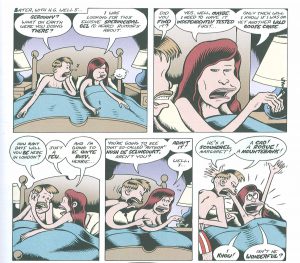

The KKK appearance combined with her attempts to bring birth control to African-American women in the South—at the behest of both Southern and Northern African-Americans, the most high-profile of whom was W.E.B. DuBois (depicted top left in the page below)—have made Sanger an excellent illustration of the way that misinformation can run rampant on the Web. I’m running out of room, but if you’re interested in untangling truth from sensationalism, this newsletter article from New York University’s Margaret Sanger Papers Project is a good place to start.

Bagge also carefully details his sources, and explains in 18 pages of footnotes what didn’t fit into his main narrative. He also does a fine job of condensing the complicated situation that led to the shutdown of Sanger’s Harlem clinic, and sparked her quest for a birth control pill:

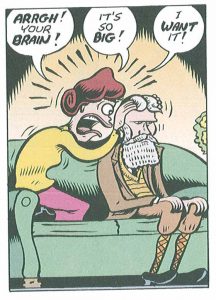

But lest you shy away from this book thinking it’s all dense history and controversy, I assure you that it’s not only fascinating, but fun, especially when Bagge depicts Sanger with historical oddballs and luminaries like Havelock Ellis and H. G. Wells:

Bagge illustrating Sanger’s life makes perfect sense to me now, and I’m looking forward to learning more about whatever historical figure he decides to take on next.

While Bagge’s biggest challenge was condensing Sanger’s life and vast accomplishments, Joe Sacco, whose most recent work I’ll review in my next post, decided to slow down and stretch his subject out—quite literally, into a 24-foot fold-out “panorama.” “The Great War” portrays, without words and in black and white, the first day of the bloody World War I Battle of the Somme. It does not promise to be “fun,” so let’s hope the sun returns to Goshen by then. In the meantime, stock up on good books from Better World Books in Goshen, Indiana, to keep you cozy, and see you in another two weeks.